Crossposted at My Left Wing.. and elsewhere.

The following excerpts and photographs in the extended text are horrible. Just fucking horrible. For all we’ve seen and heard in the media, this might as well be that episode of Star Trek where the people have concoted a CLEAN war, where people step into a machine and are evaporated and added to the list of War Casualties.

War is not clean. War is not pretty. All that fucking technology, that state of the art SHIT they’re peddling in those fucking recruitment ads? It’s used to kill and maim human beings. Just… at a further distance than the days when you had to kill a man face to face. Or chop off his arm. Or blind him.

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori my ASS.

Memory Hole Tales of the Wounded

I have posted some pictures from the sites. (There have been NO updates at either site since 2004. I don’t know why.)

WARNING: Not Suitable for Children

“They come here 19, 20 years old and when I see them leaving, missing limbs — I’ve seen up to three limbs gone off people, and I don’t think in our generation we’ve seen this amount of harm done to young people,” [Maj. Gene] Delaune says.

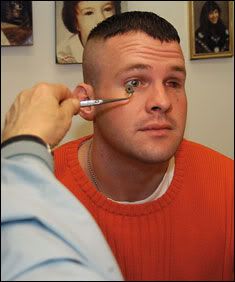

Gary Boggs

A couple miles south of the Tikrit base camp, the Humvee Boggs was riding in was badly damaged by an improvised explosive device. Shrapnel pelted the left side of his body.

“I took some nice pieces in my arm,” Boggs said. “Luckily I didn’t lose it.” But he ended up losing his left eye.

Boggs is among more than a dozen Soldiers who have lost an eye in Operation Iraqi Freedom and have been helped by Walter Reed’s ocularist, Vince Przybyla.

Staff Sgt. Maurice Craft, an Avenger crew member with B Battery, 3/4th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, was riding on Highway 5 in Baghdad Nov. 24 when an improvised explosive device hit the vehicle he was riding in. He remembers telling the driver to pull him out, and the searing pain cursing through his legs. Closing his eyes seemed to make the pain go away, but he worried that he wouldn’t wake up again.

“I forced myself to keep my eyes open,” recalled Craft. “I knew I had to if I wanted to make it home to my kids and family.”

Craft’s left leg was amputated at the knee and a titanium rod is keeping his right leg connected to his hip, which was shattered in the attack.

Landstrum was on a nightly presence patrol in Iraq in early October when a rocket-propelled grenade, IED and machine gun fire ambush claimed his left eye.

“I lost my eye; shrapnel wounds throughout my body, lost a piece of my skull and got messed up pretty good,” Lanstrum recalled. “At first, I was so messed up I didn’t think about my eye, I was happy to be alive, and, even to this day, it doesn’t bother me that I lost my eye.” Lanstrum said.

“I see guys around here missing a lot more than an eye. I’m going to take care of the one eye I have left and just carry on.”

Lanstrum said he couldn’t feel sorry for himself when three of the five guys in his vehicle died.

“Me and another guy, who lost his eye also, were the only ones to walk out of my truck so I feel pretty fortunate.”

Koch, a member of a military police company mobilized out of Fort Leonard Wood near Rolla, Mo., was driving a truck along a stretch of Baghdad highway nicknamed Ambush Alley in July when an unexploded rocket-propelled grenade hit the truck’s side mirror and bent it toward the cab.

Moments later, a bullet hit the mirror, showering Koch’s face with glass; one piece lodged in his left cheekbone. A second bullet struck the left corner of his mouth, ripped open his cheek and shattered teeth.

Koch’s assistant driver grabbed the wheel until Koch came to a few seconds later.

“I spit out the bullet and pulled the glass out of my cheek,” said Koch, 33. “He stared at me for a second or two like I had come back from the dead. I don’t imagine I looked too good.”

As a combat lifesaver, the other driver was equipped with a bag of medical supplies including field dressings – large gauze bandages Koch used to stanch his bleeding.

“Even though it was chaos, it was very efficient,” Koch said. “He was on the radio with one hand and handing me bandages with the other. And I was driving with one hand and stuffing bandages in my mouth with the other.”

Koch is back at Fort Leonard Wood for plastic surgery, root canals on damaged teeth and bone grafts for his jaw. He wants to return to Iraq.

Sgt. Derick Hurt returned Friday to a small town in Missouri, a place he wasn’t sure he’d ever see again.

Lying face down in an Iraqi street three months ago, the 26-year-old infantryman almost bled to death after grenades tossed from a rooftop exploded into his Humvee and blew his right leg apart.

At times, his pain and depression have been so intense that his family and girlfriend found him barely recognizable on visits to Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

For now, things are looking up. Hurt’s prosthetic leg fits well, and he’s learned to walk smoothly…

It was an ordinary Saturday in Mosul, where his unit in the 101st Airborne Division had been assigned to military police duties since May, helping to maintain public order, Hurt said in an interview last week at Walter Reed.

“We were heading down the street, one we went down a million times,” he said. ”There was nothing in the street. The next thing I knew, I saw a big orange flash right in front of me. A couple of seconds later, another one. My ears were ringing. I knew I’d been hit.”

Only later did Hurt learn that two grenades thrown from a roof had landed in front of his unarmored Humvee and bounced against its underside. He’d placed sandbags all over the floorboard to protect it, except for the section where the gas pedal and brake were.

“The force of the grenades came right through that area, the thin piece of metal – tore it right off,” he said. “I was holding the steering wheel. I was numb. I couldn’t move my arms. I noticed the truck had died, was veering off the side of the road toward a semi. I thought I was going to get a head injury. I couldn’t move my legs, so I used my torso to bail out. I think that’s when I broke my wrist and messed up my hand.”

Prone on the curb on his stomach, he tried to see what was wrong with his legs, but couldn’t turn to look at them.

“There were more bombs going off and so much smoke I could barely see. I thought, ‘This is it. I’m going to die here, just like a vegetable on the ground.’

“Then I heard one of my guys yelling my name. I thought, ‘They’re here! They didn’t just run off and leave me!’ I tried to yell, ‘I’m here,’ but I couldn’t; I’d lost so much blood that nothing came out. Thirty seconds later he found me. The first thing he said was, ‘Holy (expletive).’ I said, ‘Don’t say that.’ That’s when I knew something was very badly wrong.”

Soon a handful of soldiers surrounded him. One used wire as a tourniquet, causing Hurt to yell in pain, but the soldier said that if he didn’t cut off the circulation, Hurt would bleed to death right there.

“One thing I remember is asking everyone for water. They said I couldn’t, it would make me bleed more. I was never so thirsty in my life. I tried to reach for their canteens. I was thinking if I don’t get water, I’m going to die.”

They carried Hurt to a Humvee.

“That’s when I saw my legs. One of them was half gone, the other was all battered up. My foot was still there, hanging on by something as big around as my finger. One of the guys lost his balance and stepped on my foot. I felt pain, so I assumed it was a nerve attaching it.”

They drove Hurt to an intersection, where a helicopter landed and took him to a local hospital. He was given drugs that knocked him out, and the next thing he remembers is waking up in Germany. He arrived at Walter Reed on Sept. 21.

As Julia Harvey stood alone in her kitchen, unable to calm her wailing 3-week-old daughter, she peered at the ceiling and told God,

“I need him home! And I need him home right now!”

Within a week, her husband, Florida National Guard Spc. Travis Harvey, was back in the States. But the homecoming hasn’t turned out how Julia or Travis Harvey had hoped.

Harvey, like thousands of soldiers wounded in Iraq, returned home to his own private war. He’s still in agonizing pain. He can’t work. And his marriage is suffering.

“I couldn’t do it by myself anymore,” said Julia Harvey, 27. “But this is not what I had in mind.”

Travis Harvey nearly bled to death in a July 15 mortar attack, in which a piece of the softball-sized mortar pierced his right leg, splitting it open. The shrapnel then lodged in his left leg, shattering the bones. Another piece of shrapnel hit his left arm.

Lying alone on the concrete, Harvey, a former medic, shoved his fist into the open wound of his right leg to slow the spurting blood.

“Oh, my God; why me?” he thought. “I’m dead.”

Then he thought about Julia and Alexa, the newborn daughter he had never seen, waiting for him at their Ocala, Fla., home.

“I made a decision in my mind to go home,” he recalled. “I thought, `OK, you’re awake, you’re conscious.’ I pushed all the negative thoughts away. Then I knew I was going to make it.”

Harvey, 27, returned to a wife he had wed only days before his January 2003 deployment and to a baby born while he was about 6,900 miles away in Iraq.

Previously extremely active, holding three jobs at a time, he yearns to provide for his new family and help around the house. But his injuries make that impossible.

His wife was forced to return to work while he stayed home nursing his injuries and taking care of their baby. The stresses of the new roles for both partners created major friction in the marriage. Travis began taking antidepressants in addition to painkillers. The couple fought constantly.

“While he was gone, I had to take the reins,” Julia Harvey said. “He had his own big horse to deal with in Iraq. When he got back, we had to hand each other one of the reins. It was a huge adjustment.”

Travis Harvey said he has difficulty articulating when he is in emotional pain. He tried to tough it out, but it manifested as anger.

“We argued about everything,” Travis Harvey said. “There were yelling matches. After two weeks, we couldn’t live together.”

“We needed a break – a serious break,” Julia Harvey said.

Within three weeks, the newlyweds split. Travis moved in with his grandmother in Lake Panasoffkee, Fla. Travis and Julia began marriage counseling….

Now, Travis spends his days taking care of 5-month-old Alexa while Julia works as a receptionist. The couple is back together and trying to make their marriage work.

Travis will begin physical therapy after his wounds heal. While on medical leave, he is being paid as if on active duty, about $2,600 a month. Eventually, the military will place him on disability.

He had planned to serve 20 years and retire. Now he’s glad to see his military days behind him.

“Iraq sucked,” he said. “Twelve-hour shifts, living in hot concrete hangars, no toilet. (Ready-to-eat) meals most days. Then I almost died.”

Here are the pictures. The 2 most graphic are at the bottom, in case you wish to skip them.

Justin Burgess (with Denzel Washington)

James Wright

Albert Ross

Robert Jackson

Jose Martinez

Unidentified American Soldier

Unidentified American Soldier

I weep for humanity.