originally posted on MyLeftWing

Winter, 1917.

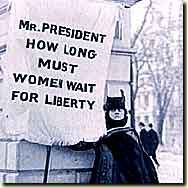

At the gates of the White House, Alice Paul stood silently with a small group of members of the National Women’s Party. They held signs that asked: “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?”

Their efforts were ignored. Then on April 6, 1917, the United States entered World War I.

The suffragists’ signs became more pointed. They taunted Wilson, accusing him of being a hypocrite. How could he send American men to die in a war for democracy when he denied voting rights to women at home? The suffragists became an embarrassment to President Wilson.

As the women’s vigil went on, the police stood by as spectators began to assault the picketers, both verbally and physically.

Note – this diary is largely adapted from two sources, cited at the end.

Please read on…

Eventually the police did act – In July of 1917, they began arresting the suffragists on charges of obstructing traffic.

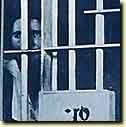

Initially, the charges were dropped. As the protest continued, the women were sentenced to jail terms of just a few days. But the suffragists kept picketing, and their prison sentences grew.  Finally, in an effort to break the spirit of the picketers, the police arrested Alice Paul. She was tried and sentenced to 7 months in prison Paul was placed in solitary confinement.

Finally, in an effort to break the spirit of the picketers, the police arrested Alice Paul. She was tried and sentenced to 7 months in prison Paul was placed in solitary confinement.

For those of us who tend to think this administration and our society are in uncharted waters – read that last paragraph again. A US citizen sentenced to 7 months – and placed in solitary – for the crime of holding a sign outside the White House. Things ARE bad now – and we have overcome great obsticals and threats to justice and freedom before.

Miss Paul (her preferred name) began a hunger strike, soon others joined her. “It was,” Paul said later, “the strongest weapon left with which to continue… our battle . . .”

In response to the hunger strike, prison doctors put Alice Paul in a psychiatric ward. They threatened to transfer her to an insane asylum. Still, she refused to eat. Afraid that she might die, doctors force fed her. Three times a day for three weeks, they forced a tube down her throat and poured liquids into her stomach. Despite the pain and ilness the force feeding caused, Paul refused to end the hunger strike–or her fight for the vote.

The struggle for women’s suffrage had begun almost 70 years earlier in 1848, in Seneca Falls, NY. Early feminist had been actively involved in the Abolitionist and other social movement – but came to realize that even there they were relegated to drudgery and denied leadership roles. They were largely denied the chance to attend college, to become doctors and lawyers, and to own their own land. If they could win the right to vote, they could use their votes to open the doors of the world to women.

Pioneers such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony led the women’s rights movement. In 1878, the first women’s suffrage amendment was presented to Congress, but ignored. The amendment was reintroduced every year for forty years. During that time, it was not brought up for a singe vote.

By the time Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party began their suffrage campaign, the old leaders of the women’s movement were gone. But support for the suffrage amendment had grown. Women were already voting in twelve western states. And in 1916, Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first women elected to Congress. Yet Congress was no closer to passing the suffrage amendment than before and the suffragist movement’s focus has switched to the states.

In 1909 while studying in England, she joined the ranks of the founder of the British suffrage movement, Emmeline Pankhurst, and her daughters Sylvia and Christabel. She participated in a variety of demonstrations and learned their tactics, which included marches, pickets of Parliment, and hunger strikes. While there, Paul was imprisoned three times.

In late 1912, Miss Paul persuaded the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), headquartered in New York City, to appoint her co-chair of its near-defunct Congressional Committee in Washington, DC.. Lucy Burns, an American suffragist she had met in a London police station after they had both been arrested became vice-chairman. Together they would reinvigorate the campaign for a national amendment,

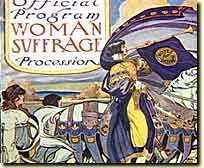

Two months later, [they] staged a suffrage spectacle unequalled in the political annals of the nation’s capital, taking advantage of the festive arrangements and publicity potential surrounding Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. On March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration,

Miss Paul, a master of spectacle and street theater, coordinated a march of some eight thousand college, professional, middle- and working-class women, in costumed marching units, each with its own banners. Leading the parade in flowing white robes, astride a white horse, was lawyer and suffragist Inez Milholland Boissevain, followed by suffrage floats and marching units going down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol past the White House.

By the end of 1916, several organizations coalesced into the National Woman’s Party (NWP) under Alice Paul’s leadership. NWP used a variety of tactics to dramatize the suffrage movement and sway public and political support in its favor. One of the most successful was having suffragist who had been released from jail ride a train called the Prison Special, dressed in prison garb, on a speaking tour throughout the country.

Another was automobile petition drives throughout the West; as suffragist made their way across the country, they stopped in cities and towns along the route and secured the signatures of hundreds of thousands of women and men on suffrage petitions to be delivered to Congress.

When such efforts continued to fall on deaf ears in the Capitol, the NWP became the first group of American citizens to dramatize its political protest by picketing the White House. They were known as Silent Sentinels, and with the rhetoric of Liberty during WWI, they had become an embarrassment to President Wilson.

This brings us back to July 1917. Hundreds of women were arrested on charges of “obstructing sidewalk traffic.” Many, were convicted and sentenced to prison, some, like Miss Paul, multiple times and with increasing terms.

The conditions in which the suffragists were held at the Occoquan Workhouse were appalling. Blankets were rarely washed (one source says once a year). There were open toilets, which could only be flushed from outside the cell by the guard, who might or might not come when called. Women who were on a hunger strike were brutally force-fed.

Doris Stevens, one of the prisoners, wrote in the Suffragist of August 11, 1917:

No woman there will ever forget the shock and the hot resentment that rushed over her when she was told to undress before the entire company. . .We silenced our impulse to resist this indignity, which grew more poignant as each woman nakedly walked across the great vacant space to the doorless shower . . .

In a complaint filed by Lucy Burns concerning conditions at the Workhouse, Ms. Burns stated:

The water they [the suffragists] drink is kept in an open pail, from which it is ladled into a drinking cup. The prisoners frequently dip the drinking cup directly into the pail. The same piece of soap is used for every prisoner. As the prisoners in Occoquan are sometimes afflicted with disease, this practice is appallingly negligent.

November 15, 1917, was the Night of Terror at Occoquan:

Under orders from W. H. Whittaker, superintendent of the Occoquan Workhouse, as many as forty guards with clubs went on a rampage, brutalizing thirty-three jailed suffragists. They beat Lucy Burns, chained her hands to the cell bars above her head, and left her there for the night. They hurled Dora Lewis into a dark cell, smashed her head against an iron bed, and knocked her out cold. Her cellmate Alice Cosu, who believed Mrs. Lewis to be dead, suffered a heart attack. According to affidavits, other women were grabbed, dragged, beaten, choked, slammed, pinched, twisted, and kicked.

Still the suffragist would not abandon their cause. Alice Paul responded to such treatment with another hunger strike and in October 1917, severely weakened, she was taken by stretcher to the prison hospital.

There she was held incommunicado: no attorney, no member of her family, no friend was allowed to see her. Prison officials threatened her with transfer to the jail’s psychopathic ward and St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, the Government’s institution for the insane, if she did not break her hunger strike. When she refused, she was taken by stretcher to a cell in the prison’s psychopathic ward and treated like a mental patient. At night, she could not sleep for more than a few minutes at a time because an electric light was aimed at her face once every hour all through the night. She lived in dread of being transferred to St. Elizabeth’s. After a week in the ward, through the intercession of a supporter, Dudley Field Malone, the well-known lawyer and liberal, she was returned to the jail’s hospital. A week later she was released.

Eventually word of this treatment became widely know and the inflamed public opinion. Newspapers carried stories about the jail terms, beatings and forced feedings of the suffragists.

The stories personalized the issues and support for the Suffragist cause quickly grew . On January 9, 1918, WIlson announced his support for suffrage. The next day, the House of Representatives narrowly passed the Susan. B. Anthony Amendment, which would give suffrage to all women citizens. On June 4, 1919, the Senate passed the Amendment by one vote.

With Paul’s leadership of campaigns throughout the country, a little more than a year later, on August 26, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment. That made it officially the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

In November1920 the women of the United States voted in a presidential election for the first time.  It had taken seventy-two years beginning with the first Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, in July 1848 — spanning two centuries, eighteen presidencies, and three wars — for American women to get the right to vote.

It had taken seventy-two years beginning with the first Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, in July 1848 — spanning two centuries, eighteen presidencies, and three wars — for American women to get the right to vote.

As I think about our times – the infamous Pier 57 in NYC, about Camp Casey – I’m frustrated that, in many ways, we’re still close to where we started. (for example – after winning this fight, Miss Paul started working on something called the Equal Rights Amendment…)

but Miss Pauls story reminds me that the challenges we face are neither new nor unique – and she shows us that our efforts are not futile – despite difficulties – we can overcome, we can win victories – we can change the wind.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Photos and text

http://pbskids.org/wayback/civilrights/features_suffrage.html

Additonal text:

http://www.moondance.org/1998/winter98/nonfiction/alice.html

Additional Background:

http://www.alicepaul.org/alicep.htm

Please Note – I do lift Paul up as one of my heros – but she is not perfect – one glaring issue is her lack of public support for racial equality. Her private letters show her not to be a bigot, but her, and her groups, public stances are open to criticism. I do not merely dismiss this as a product of the times, but at the same time I don’t think such issues warrant dismissing her role in the victory of 1920. I commend the discussion around these issues in the original MLW diary – in particular shannika’s comments – for some other viewpoints on this. I would echo srliberals comment “Our Heroes are still human. Let us celebrate our Heroes achievements and learn from their mistakes.”

I think we progressives should know more about Alice Paul – so I contribute this diary. I encourage those with other heros to contribute similar diaries. (and I encourage people to check out a person I first heard of in shannika’s comments – Ms. Ida Wells Barnett . Another new hero for me 🙂

Who else should I know about? Who are your heros?

family commitments. If you enjoyed this piece – I encourage you to recommend it so that others can learn about Miss Paul.

Maybe I just wasn’t paying attention in school the right day, but I encountered Alice Paul only in the last year or so – and she quickly became one of my heros.

I’d heard of Seneca Falls, I knew the amendment passed in 1920, but I didn’t know the story of how. I think it applies rather poiniantly to our current struggles. I think it’s shameful how quickly we forget our history – we too often think our times and challenges are unique – and certainly they have new aspects – but think of what women like Alice Paul were up against – and look at how they pressed on – and even won – their fights.

The 1920’s hold a number of parrallel’s to our modern fights – I think we’d do well to remember (or learn about) them. Another time I’ll write a bit about a sermon given, I believe in 1927, titled “Shall the Fundamentalist Win?” Not much new under the sun I guess 🙂

Hope you enjoyed this. Please do click through to the sources – almost all the credit goes to them, I just did some arranging – and again – I don’t think our Heros have to be perfect – I think they should be people we learn from – good and bad.

Great diary. It’s amazing isn’t it how little of ‘history’ is our history books. I don’t even remember when I started realizing this but I’d say it had a lot to do with the resurgent feminist movement in the 60’s…and trying to get the ERA passed..haha those 24 little words scared people shitless apparently.

There’s a dvd out called ‘Iron Jawed Angels’ about this time in our history with Hilary Swank(don’t remember who else) that was very good. Knowing more about the history of the fight to gain the ‘right’ to vote I now cringe when I hear most people say we were ‘given’ the right to vote…like one day Congress just up and decided hey lets give women the vote…with no effort on the part of women for so many, many years.

Funny you should mention Ida Wells Barnett..I just was looking through a book of mine a few days ago and rereading the short history of her in there-pretty remarkable.

http://tinyurl.com/cv8j4 This link will take you to information about a woman, Sarah Breedlove Walker, who became the first woman to become a millionaire. A woman born in in 1867 to parents who were sharecroppers, former slaves. With no schooling and only her own perserverence, ingenuity and invention she ended up starting a business-to do with hair products and branching out-she eventually employed at least 3000 people. When she died her will stated that a woman must continue running her company. If you want to read more follow the link.

i’m very pleased to recommend you. i will see if i can get some friends to do the same. we are not that far removed from alice paul, you know. when cindy sheehan goes to washington in september, lord willing the only difference will be she won’t be able to stand at the white house gates.

but i think our biggest battle lies not with the war in iraq. it lies with defeating the males in government about who controls our reproductive rights.

i will use alice paul as my touchstone, and inspiration.

thanks so much for reminding me of her.

It’s sadly ironic that these brave women should have worked so hard and suffered so much to get a right that so many women today chose to ignore.

By the way, there is a really great resource site for historical information about feminism called No Turning Back which is in turn a based on the book “No turning back: the history of feminism and the future of women” by Estelle B. Freedman.

thanks for that link..another good one to be saved.

Thanks Simifuigplex. Excellent diary.

I think it is an important thing for us to take a look at history and realize the lessons there.

What worked?

What didn’t?

What was the battleground?

Who stood on each side?

What are the parallels to today?

What was won?

What is left over to be won today?

Progressive… something that moves constantly forward. We are still fighting the same battles our foremothers and forefathers fought back then. Our children will be fighting those same battles in their lifetimes.

Progressive… constantly, inexorably, moving forward. We cannot be stopped… except by ourselves. Alice Paul is a perfect example of that. She never stopped. Look at the horrors that she faced… and she never stopped.

We must always be doing battle to move the cause of the people forward. We have won great victories throughout history and we will continue too. The other side continually loses… but we’ve also come dangerously close to losing a hundred years worth of gains. We’ve lost the momentum and it has swung to the other side. As in sports momentum is important and we have to turn this thing around and become the steamroller of history once again.

Never give up.

Never give in.

Si! Se puede!

What a wonderful diary.

I suppose you’ve seen Iron Jawed Angels, the HBO movie that stars Hilary Swank as Alice Paul?

I think movies like this are a wonderful way to introduce people — especially young women — to these stories because the dramatizations capture people’s attention.

Available in DVD and VHS.

I’ve actually not seen it…

yet.

somehow the first I’d heard of it was in a response to the diary over on MLW – planning to get the DVD. I first encountered her while I was writing a sermon and doing some background to lead into my “introduction” of Rev. Beth Stroud as one of my heros. Wanted to pull in an early suffragist and realized other than a couple names I knew damned little about the movement. Link from a link and there I was meeting Alice Paul – and a lot about our history I’d not known. (also encountered Bayard Rustin (another person I’ll write about soon) the during the same search.

I think the popular conception of the Suffragist movement is that women in pretty dresses marched a few times and a couple decades later got the franchise…

one of my reasons for writing this piece is that so often we in the modern age seem to think that if we just hold a big rally everyone will suddenly see the light. I think such rally’s are wonderful and necessary things – but our misconception of history I think contributes to our current frustrations. Change – especially big changes of popular opinion – are painful and slow.

We are standing on the shoulders of giants.`

actually got up in arms about the treatment of the suffragists when now no one seems to care about Gitmo, other than to revel in its cruelties.

That may be the most depressing and disturbing thing about this whole administration and the public response. How the hell anybody buys the “a few bad apple’s” dismissal makes me seriously wonder if the nation and ideals I love really exists anymore.

I think it’s salvageable – but sometimes I really wonder. America does NOT do that sort of thing (well, we do – I know about our history in Central America…. – but we don’t admit it and blow it off….)

I’d really rather we live up to our ideals instead of down to our worst impulses…

Simplexity … for all that want to learn more and to be inspired by the women who came before us there’s a PBS special by Ken Burns that is exceptional. It’s the story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony but even more than that, it’s the history of what women have done to come as far as we have.

It’s difficult to watch and listen to it and not get teary- eyed and scream into our souls that we as women will pick up the mantle and bring equality to each and every woman, whether they are with us or not, because it is the right thing to do, right for us and right for our country.

So enjoy Not Ourselves Alone. It will lift you up, it will put a fire in your belly, it will inspire you, it will make you sure we can do this, we must do this. Just click on the pictures of Elizabeth or Susan and the video and audio will start.

http://www.pbs.org/stantonanthony/

Let’s not wait another day, we simply can’t afford to. We have to, we must march, we must petition, we must demand equality. How can we sleep if we do not? How can we look at ourselves in the mirror if we do not?

Not Ourselves Alone, we are not alone, we have never been alone. The Elizabeth Cady Stantons, Susan B. Anthonys and Alice Pauls have paved the way, it is our duty, it is our calling, it is our honor to bring equality to us all. How can we not, we’ve got the stuff of powerful, steadfast women behind us.

What women want is what men want. They want respect. Marion von Savant