We were crawling along an unfamiliar side street of South Pasadena last Friday, on our way home from dinner with the family of an Iranian friend, a one-time fugitive from the brutal Shah and brother-in-law of a three-term southern California Congresswoman. A black Lincoln Navigator edged away from the curb in front of us. Streetlights burn dim and stand far apart in the neighborhood, and I didn’t get a good look at the bumper sticker on this submarine-sized car until it braked for the stop sign where the side street turns into the main drag. In crimson letters on a white background: “Nuke Iran Now!” Palpable rage embraced in three words.

I know the feeling. When I see a bumper sticker like that, I’d like to flip my special accessories dashboard open and fire a nuclear-tipped missile up the guy’s tailpipe. You know, one of those tactical mini-nukes that certain elements in and close to the Bush Administration are pushing the development of for the express purpose of being the first and second nation to have unleashed atomic warfare on the planet. Just press the Execute button and vaporize the guy and his vehicle right there in the intersection. Voilà! Problem solved. One more fanatic extinguished. Peace restored to my psyche. Collateral damage be damned.

Not being a scientist, I don’t precisely understand how my reptile brain interfaces with my cognitive lobes, but I’m pretty sure it plays a major role in launching fantasies like that one into my thought centers. Maybe it’s just a boy thing. Whatever the case, with me, it is just fantasy, and lasts a nanosecond or two before sanity returns.

With the big dogs in DC, however, preemptively employing nukes of various sizes has become official policy, a cold-blooded, calmly derived, elemental part of the Bush Doctrine, the Nuclear Posture Review and the National Strategy to Combat WMDs. Yes, they see this as a positive.

However, you can’t blame Republicans alone. During my six decades on the planet, Washington has always maintained a first-strike option. In 1978, it seemingly back off a tad by vowing it would never use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty unless they were allied with an aggressive nuclear state. In April 1996, the U.S. signed the African Nuclear Weapons Free Zone Treaty, pledging not to use or threaten to use a nuclear weapon against any of the 50 signatory states, including Libya. Less than two weeks later, however, Secretary of Defense William Perry indirectly threatened a nuclear strike against a purported a chemical weapons plant being built in the Libyan mountains 40 miles southeast of Tripoli near rural Tarhunah, which coincidentally, is the home of my stepchildren’s grandfather.

Clearly, under what has been de facto U.S. policy for a decade, and official doctrine for the past three years, any attack against Iran (which has been predicted to be just around the corner for more than a year now) might not be limited to surgical strikes with conventional weapons, as when Israel sent F-16s and F-15s in 1981 to destroy the unfinished, French-built Osiraq research reactor near Baghdad. The Iranian regime epitomizes the kind of target the new nuclear posture has been designed for.

A number of sources have suggested that an attack could come early this year, possibly as soon as late March. Maybe right around Norouz, the Equinox-timed celebration of the Iranian new year when my friend Muhammad and his two young sons, Ideen and Afreen, may be in Isfahan visiting relatives.

But let’s not get sidetracked into a dispute over timing. Past predictions of imminent assaults on Iran have proved mistaken.

For now, let’s just imagine what might happen if an attack included a nuclear strike.

Actually, in May 2005, the Physicians for Social Responsibility imagined it for us in the chillingly titled Projected Casualties Among U.S. Military Personnel and Civilian Populations from the Use of Nuclear Weapons Against Hard and Deeply Buried Targets.

Using computer software ― the Hazard Prediction and Assessment Capability developed by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency ― PSR experts modeled two single-nuke attacks, one on Isfahan, Iran, and one on Yongbyon, North Korea. In each case, the impact of a 1.2-megaton bomb was modeled.

From the HPAC calculations, we estimate that within 48 hours of an … attack, over 3 million people would die as a result of the attack. About half of those would die from radiation-related causes, either prompt casualties from the immediate radiation effects of the bomb, or from exposure to fallout. For example, the entire city of Isfahan would likely be covered in fallout producing 1000 rems of radiation per hour, a fatal dose. Over 600,000 people would suffer immediate injuries of the kind described previously. …

…within 48 hours, prevailing winds would spread fallout to cover a large area in Iran, most of Afghanistan and then spread on into Pakistan and India. There is little likelihood, in most seasons, that rain would mitigate the spread of fallout.

In this scenario, over 35 million people in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India would suffer significant radiation exposure of 1 rem per hour or above within four days of the use of the RNEP. At this rate, the 25 rem limit at which physical effects can be expected would be reached within 25 hours of first exposure, and the 100 rem limit at which more severe damage could be caused would be reached in only 4 days. (Given the lack of modern communications in this area, as well as the lack of advanced education available to the affected populations, it is unlikely that warnings would spread quickly enough to allow mitigating measures to be taken). Immediate effects would include skin burns and diarrhea secondary to gastro-intestinal cell damage. Long-term effects could include cancers. Many, if not all, of the approximately 20,000 American armed forces, intelligence and diplomatic personnel deployed in Afghanistan would be at risk of exposure at these radiation levels. While U.S. personnel could be evacuated, and would receive sophisticated medical care if necessary, this would not apply to the local population in most of the affected area.

Three million dead. Can you get your mind around that? Not me. But I can easily imagine three victims ― Muhammad, Ideen and Afreen ― vaporized, burnt to a crisp or choking up their gamma-pulverized guts. The brother-in-law and nephews of a Congresswoman prey to a first-strike U.S. nuclear attack.

The PSR scenario is a bit problematic. The B83 Bomb the doctors chose to model hasn’t yet been configured into the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator. Commonly known as the “bunker buster,” the RNEP would bury itself under several meters of earth before exploding to generate a massive shockwave to destroy an HDBT, military jargon for the hard and deeply buried targets that the Pentagon says there are 10,000 of around the planet.

Congress has twice chopped RNEP funding, with Republican Rep. David Hobson of Ohio leading the opposition. Said Hobson last March:

“Neither the Department of Defense nor the Department of Energy has ever articulated to me a specific military requirement for a nuclear earth penetrator. At DoD’s urging, I even spent an entire day at Offutt Air Force Base getting briefed by STRATCOM, but I was never told of any specific military mission requiring the nuclear bunker buster.

“The Department of Energy’s nuclear weapons complex has so many fundamental management problems that have not received sufficient Federal oversight that it troubles me deeply that Congressional opposition to RNEP generates so much attention. The development of new weapons for ill-defined future requirements is not what the Nation needs at this time. What is needed, and what is absent to date, is leadership and fresh thinking for the 21 st Century regarding nuclear security and the future of the U.S. stockpile.”

However, according to the authoritative Jane’s Information Group:

In late October, US Congressional leaders agreed to withhold USD4 million requested by the US administration to complete pre-engineering studies into the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP). Although it has been widely reported that the programme has now been cancelled, there is evidence that the RNEP project may yet continue under a new name.

Whether the RNEP remains on the Administration’s wish-list, it’s obviously not available yet. Purists thus might reject the PSR study as irrelevant scare-mongering. Lack of an RNEP does not, however, leave military planners with no options if they decided nukes were needed to blow up some of Iran’s underground nuclear infrastructure. For one, the B83 warhead that designers hope one day to make over into the RNEP is available in large quantities.

However, the smaller B61-11 is the more likely choice.

Earth-penetrating designs for nuclear warheads began under Jimmy Carter in the 1970s. Advances were made, but the design was dropped. Then, in 1984, the Reagan Administration sought an ICBM warhead that could take out deeply buried Soviet installations. Costs, the need to slow the delivery vehicle so that it wouldn’t disintegrate on impact and other troubles killed the program in 1988.

Interest was rekindled early in the Clinton Administration in an earth-penetrating design to replace the aging B53, a 9-megaton bomb (600 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb). The chosen replacement was the B61-11, an earth-penetrating derivative of an earlier nuke, the B61-7, which can be configured to yield as much as 340 kilotons ― 30 times as much as the Hiroshima bomb ― and as little as 0.3 kilotons.

It was the B61-11 that the Clinton Administration threatened to use against Libya’s alleged chemical weapons plant in 1996. When Condoleeza Rice and others in the Administration talk about nukes with “low yields,” this is what they mean.

The strategic underpinnings for these weapons was laid out in an article by Thomas Dowler and Joseph Howard in the Fall 1991 issue of Strategic Review, “Countering the Threat of the Well-Armed Tyrant: A Modest Proposal for Small Nuclear Weapons”:

“Would policymakers employ nuclear weapons to protect U.S. contingency forces if conventional weapons proved inadequate, or would the nature of our present nuclear arsenal ‘self-deter’ policymakers from using those weapons?

. . . One possible answer to these questions might be the development of nuclear weapons of very low yields. . . .

The existence of such weapons–weapons whose power is effective but not abhorrent–might very well serve to deter a tyrant who believes that American emphasis on proportionality would prevent the employment of the current U.S. arsenal against him.

“We doubt that any president would authorize the use of the nuclear weapons in our present arsenal against Third World nations. It is precisely this doubt that leads us to argue for the development of subkiloton weapons.”

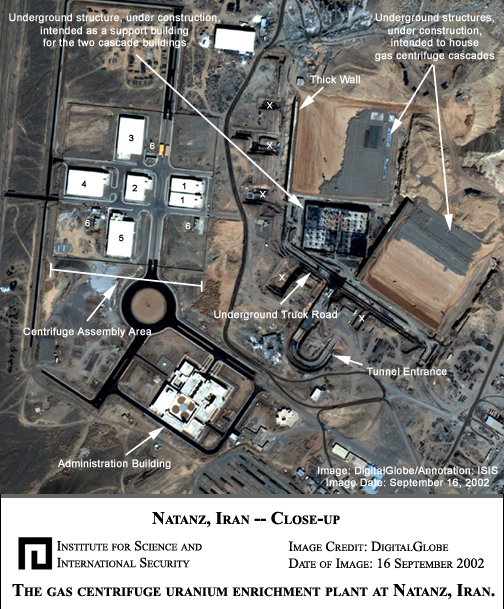

Just one problem with these “low-yield” weapons. At the subkiloton or slightly higher level, they might serve to destroy most of the shallowly buried Iranian facilities that are likely to be on the target list. However, they’re incapable of taking out the really deep, really hard targets. Exactly the kind one might expect Iran to have, say, in and around Isfahan, where not only are thereaboveground nuclear facilities of various types, but also underground tunnels for nuclear storage. How deep underground? The Feds haven’t seen fit to give me a security clearance, so I don’t have a clue. Since they’ve got photos and, presumably, spies, maybe the attack planners have it all scoped out and they know no nuke is necessary. But my intuition gives me the distinct feeling that our intelligence services are uncertain about such matters. Nor do they definitely know how deeply buried other nuclear facilities are (nor, as many believe, WHERE some of them are).

Moreover, if Iran is secretly seeking to master the building of nuclear weapons ― as those who advocate a preemptive strike argue – then it seems likely there are duplicate facilities dispersed throughout the country. Possibly dozens.

To be sure, not every site would require a nuke to put it out of business. Ninety-five percent are probably vulnerable to conventional weaponry. For instance, the Bushehr reactor being built by the Russians wouldn’t survive a conventional attack any better than did Iraq’s Osirak. But if there are any really entrenched facilities, even half a megaton, much less a third of a kiloton, won’t do the job.

According to a National Research Council study, a nuclear warhead set off at the surface would take 25 times more power to destroy a buried facility than would a bomb exploded a few meters underground. Nonetheless, it would require a 300-kiloton earth-penetrating nuclear weapon to destroy a target 650 feet underground, and a 1-megaton weapon to destroy a hardened 1000-foot-deep facility.

The NRC concluded that:

Conclusion 3. Current experience and empirical predictions indicate that earth-penetrator weapons cannot penetrate to depths required for total containment of the effects of a nuclear explosion.

{snip}

Conclusion 6. For attacks near or in densely populated urban areas using nuclear earth-penetrator weapons on hard and deeply buried targets (HDBTs), the number of casualties can range from thousands to more than a million, depending primarily on weapon yield. For attacks on HDBTs in remote, lightly populated areas, casualties can range from as few as hundreds at low weapon yields to hundreds of thousands at high yields and with unfavorable winds.

A chasm exists between the NRC’s million casualties at the top end and the 3 million deaths posited by the Physicians for Social Responsibility. Some might call this an ideologically driven difference. I call it the uncertainty of predicting the slaughter when only two rather smallish atomic bombs have ever been used. Modeling the death toll can scarcely be anything better than an inexact science. It seems possible, however, that a burst of arrogance and fission over a single target could wipe out more Iranians than the number of Americans killed in all wars since 1776.

But, if the Administration decides to attack Iran, will it opt for nukes? Are the President and his advisors willing to incinerate and irradiate a few hundred thousand or a few million Iranians for what they claim are America’s (and the world’s) security interests? Can they possibly be as covertly callous as the folks at NukeIran.com who openly say they don’t care about the massacre of foreign babies? Many on the left, like some at Antiwar.com, say the Administration doesn’t care and that a nuclear attack on Iran is inevitable.

William Arkin at the Washington Post doesn’t buy it. He thinks a conventional attack would do the job just fine. (He also thinks the speculation about an “imminent” attack is wrong.)

Since at least the middle of 2004, U.S. long-range bombers and submarines have been on alert to carry out an attack on weapons of mass destruction targets that could potentially threaten the United States. At Strategic Command (STRATCOM) in Omaha, the global strike plan has been written and refined. The choreography for bomber and cruise missile attacks has been arranged. Actual targets have been selected, and WMD activity is monitored, resulting in constant revisions of the choreography.

In May, I wrote that the plan also includes options to use nuclear weapons. But the attractiveness and feasibility of the new global strike planning is that a disarming blow can theoretically be delivered with conventional weapons alone.

However, as we’ve seen, the strategic philosophical stirrings that drove the Clinton Administration to develop and deploy earth-penetrating nukes are now official doctrine. President Bush has, moreover, surrounded himselfwith “nuclear hawks” – National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley, Stephen Cambone, Keith Payne, Linton Brooks, Robert Joseph, John Bolton and J.D. Crouch II, all of them men, like Payne, who have sought to provide America with the attitude and technology to engage in “nuclear war rationally.”

Any one of them could have been driving that Navigator I followed last week. What better practical test for their views than a nation whose new leader’s rancid rhetoric can be spun for the American public into something like “he was just asking for it.” Even the Bush Administration’s old nemesis, Jacques Chirac, has joined in with his own threat.

And, finally, scariest of all, we’ve been told that the planning for a strike, with nuclear options, is at the ready.

Despite all these portents, there are countervailing forces. Not least among them is practicality. Short of a full-bore aerial assault on scores if not hundreds of the 450 targets some have identified as nuclear and military assets in Iran, there is no guarantee that an attack will do more than temporarily postpone the country’s acquisition of nuclear weapons if that’s what it wants to do.

Does the Administration have the stomach for an attack of that magnitude and the inevitable diplomatic storm? Will they simply say to doubters around the table that Iran will have to be attacked someday, so we might as well get it over with now? Maybe. I’m no Pollyanna when it comes to the current regime’s willingness to exceed legal and moral boundaries. We know too well how narrowly considered was the thought that went into what would happen after the attack on Iraq.

On the other hand, the very mentality behind the bunker-buster philosophy is that the world – and the majority of the American populace – would be so repulsed by the massive “collateral damage” caused by using big nukes that only “low-yield” weapons used surgically are politically acceptable. As we have seen, however, such nukes can obliterate shallow installations, but not the toughest targets, where a smart regime could be expected to bury its most critical facilities.

Thus, the nuclear hawks are left with two options, a relatively – ahem – restrained attack focused on a few major targets. Relatively restrained, but still with a potential for, at least, hundreds of thousands of casualties, and the best consequences being to postpone for a few years an inevitable Iranian nuclear breakout. Or an all-out, nation-wrecking, conventional and nuclear attack on hundreds of targets potentially with millions of casualties.

Then, too, there’s the potential blowback. Here’s an excerpt from retired intelligence analyst Jeffrey White at The Washington Institute:

Long-term Reaction. In the long-term, Iran would attempt to take steps that would insure itself against another attack on its nuclear program or a broader attack on the regime. Tehran would almost certainly rebuild the program, reflecting its status as a high-value national asset. Unless significant numbers of scientists and technicians were killed in the strikes, there is no reason why Tehran could not restart the program; as long as it possesses the necessary knowledge and skills, Iran will have the basis for such a program. Indeed, Iran would likely accelerate both its nuclear and long-range-missile efforts in order to achieve a measure of deterrence as quickly as possible. The regime would also increase security for the program by instituting or increasing hardening, dispersal, redundancy, and active defense measures.

In addition, Tehran would likely plan and then implement asymmetric attacks on high-value U.S. and allied targets.

How anyone can see more than the shortest of short-term military benefits from either option is beyond my comprehension. Whatever their stated views on the subject, whatever their drive to deploy new weapons to fit their doctrine, it’s difficult for me to see how the nuclear hawks will be able to persuade others in the Administration of the efficacy of their approach. But, then, I can’t imagine how they persuaded themselves.

A word about Israel. In line with the Begin Doctrine, preemptively striking Iran has been tossed back and forth at the highest levels in Tel Aviv for at least seven years, ever since Tehran began testing its sophisticated Shahab-3 missile. More frequent and tougher talk arose as it appeared Iran was determined to build a full-service, mine-to-turbine nuclear industry with the capacity to divert and enhance a portion of its enriched uranium to the making of Bombs. Eventually, it’s assumed, Bombs get married to missiles.

Public statements from the Israeli government have been blunt – Iran will not be allowed to have the Bomb. And with hawkish attitudes regarding Iran found across the Israeli political spectrum, a preemptive strike could be expected to garner wide popular support. Still, unless directly and imminently threatened – in the old sense of those words – would Israel dare include the delivery of a few samples from its putative arsenal of nukes in any attack on Iran? Surely, even among the most militant, that would be a last resort.

What then about a conventional assault? How effective would it be? Most targets connected to Iran’s nascent nuclear industry could be taken out with conventional weapons. Dr. Jeffrey Lewis has taken a comprehensive look at what might be actual targets. However, assuming not all the technicians and scientists are killed, any non-nuclear attack would leave a high possibility that crucial aspects of the Iran’s nuclear capacity would survive and be rebuilt.

The same applies whether the U.S. or Israel were to carry out an attack. The Israeli air force would be operating at the far end of its logistical capabilities to strike Iranian nuclear-related targets. This would be no Osiraq. The U.S. has far greater forces, yet anything more than a modest attack on a few targets would encounter great obstacles. A good rundown on those can be found in the December 2004 Atlantic Monthly, which published the results of its war game on the subject.

.

You can also get a good sense of the back-and-forth on this matter by reading the Institute for Strategic Studies’ October 2005 Getting Ready for a Nuclear-Ready Iran. Especially check out Part III on “Is There a Simple Military of Sanctions Fix?” An excerpt from those 322 pages:

Yet, the truth is that Iran soon can and will get a bomb option. All Iranian engineers need is a bit more time 1 to 4 years at most. No other major gaps remain: Iran has the requisite equipment to make the weapons fuel, the know-how to assemble the bombs, and the missile and naval systems necessary to deliver them beyond its borders. …

As for eliminating Iran’s nuclear capabilities militarily, the United States and Israel lack sufficient targeting intelligence to do this. In fact, Iran long has had considerable success in concealing its nuclear activities from U.S. intelligence analysts and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors. (The latter recently warned against assuming the IAEA could find all of Iran’s illicit uranium enrichment activities). As it is, Iran already could have hidden all it needs to reconstitute a bomb program, assuming its known declared nuclear plants were hit.

(Reading that evaluation, some will argue that Iran isn’t one or four years away from a Bomb, but more like a decade, according to a National Intelligence Estimate, based on CIA assessments. Whatever may be said about Iran’s nuclear capabilities, I, for one, would take the CIA’s perspective with a grain of salt given its previous failures – the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Pakistan A-Bomb being the first that come to mind.)

Even NeoCon Michael Ledeen sees attacking Iran as a difficult project. Indeed, he blames the Bush Administration for wasting five years by not firmly and intensively backing internal forces for regime change in Iran. It’s not an Iranian A-Bomb that should worry the West, he argues, but rather who controls it.

We now hear cries for violent action from those once aptly characterized by Senator Henry Jackson as “born-again hawks,” Democrats and Republicans suddenly willing to talk tough about sanctions and military strikes against Iran. This is only to be expected. Having failed to pursue serious policies in the past, we are left with distasteful options today, and the pundits’ and solons’ chest pounding shows it. They do not expect the “hard options” to be embraced; this is posturing to the crowd, this is political positioning of the most cynical sort.

{snip}

You want to bomb the nuclear facilities? Do you really believe that our intelligence community is capable of identifying them? The same crowd that did all that yeoman work on Saddam’s Iraq? The CIA that once received accurate information on Iranian schemes in Afghanistan, only to walk away from the sources that provided it? The CIA that, three times in the past 15 years or so, seems to have had its entire “network” inside Iran rolled up by the mullahs? And even if you believe that we have good information about the nuclear sites, are you prepared to deal with the political consequences, in Iran and throughout the region? Do we even know, with any degree of reliability, what those are? Look at the problems we now face in Pakistan, after a handful of innocents were killed in an assault against a presumed terrorist gathering. Then imagine, if you can, the problems following hundreds, or thousands of innocents killed in raids inside Iran. Are you prepared for that?

{snip}

Our failure to support revolution in Iran is already a terrible embarrassment, and risks becoming an enormous catastrophe. Almost everyone who writes about the chances for revolution takes it for granted that it would take a long time to come to fruition. Why must that be so? The revolutions in countries like Georgia and the Ukraine seem to have erupted in an historical nanosecond. Nobody foresaw them, everyone was surprised. Who imagined the overnight success of the Lebanese people? How long did that take? The entire region is awash with revolutionary sentiment, and nowhere more than Iran. Why assume — because no one can possibly “know” such things — that it would take a long time?

Given all the evidence that a attack – nuclear or conventional – is illogical, impractical, and, in the long run, counterproductive to national security, I’d like to be able to say I’m as certain as I was nine months ago that the U.S. will avoid taking the military option in Iran.

For the sake of all the Ideens and Aveens in the world, I’d like to be able to say that this and this and this are just chest-thumping. For the sake of all the Sallys and Sebastians, I’d like to be able to say I’m certain the decision to attack Iran hasn’t been, like the decision on Iraq, made long before there is any public debate on whether there should be an attack. I’d like to be able to say that I’m certain cooler, calmer, wiser heads will create a negotiated or other non-military solution to this increasingly scary stand-off.

I’d like to be able to say all that. But I can’t.

[Cross-posted at The Next Hurrah.]