(cross-posted at Deny My Freedom and Daily Kos)

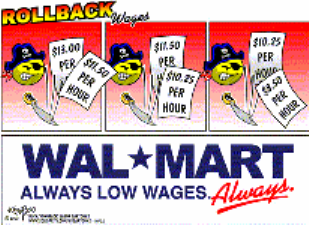

The topic of Wal-Mart is a difficult one to broach. On one hand, the prices that Wal-Mart charges are legendarily low, in large part due to their highly efficient supply chain system. Its praises have been sung far and wide by business leaders and in the marketing textbooks that business students like myself study from. However, the retail giant also has its dark side as well. Whether it be the lawsuits that the company has faced from employees, their lack of good health care coverage, or their strict anti-union policies, there’s something for everyone to dislike about how Wal-Mart does business. Sure, it may make their profits larger (they only suffered their first fall in quarterly net income this past quarter), but it doesn’t mean that they are treating their employees any better.

Recently, several high-profile Democrats, including several possible contenders for the party’s presidential nomination in 2008, have appeared at anti-Wal-Mart rallies around the country. That being said, is it really smart for us to use Wal-Mart as the proxy for the wealthy contributing to the middle class crunch? It’s certainly a question that merits some debate within the blogosphere, which has never had many kind words for the low-priced retailer. I think that while it is admirable to put public pressure on Wal-Mart to change their practices, it is not something that is necessarily a political winner.

One of the problems with criticism of Wal-Mart lies in slamming the wages it pays its workers. Here’s what Senator Joseph Biden (D-DE) had to say about the wages the company pays its employees:

“My problem with Wal-Mart is that I don’t see any indication that they care about the fate of middle-class people,” Mr. Biden said, standing on the sweltering rooftop of the State Historical Society building here. “They talk about paying them $10 an hour. That’s true. How can you live a middle-class life on that?”

In addition, Wake-Up Walmart echoes similar sentiments on its ‘Real Wal-Mart Facts’ page (linked to above):

The average two-person family (one parent and one child) needed $27,948 to meet basic needs in 2005, well above what Wal-Mart reports that its average full-time associate earns. Wal-Mart claimed that its average associate earned $9.68 an hour in 2005. That would make the average associate’s annual wages $17,114.

It’s no surprise that the salary Wal-Mart pays puts people at near-poverty levels – but it’s not any news that many working Americans don’t make a livable wage. However, there are several problems with this criticism. First, it’s higher than the federal minimum wage, which has sat at $5.15 for almost 10 years. It seems somewhat wrong-headed of us to focus on the wage Wal-Mart pays its workers when there are several other companies – fast-food restaurants, for example – that pay its employees even less. The average of $9.68/hour is higher than the highest lawfully mandated minimum wage at the current time ($8.82, in San Francisco). Democratic criticism of Wal-Mart’s wages make it difficult to square away with our support of increasing the federally mandated minimum wage. The stand-alone minimum wage raise in Congress (along with the version that was tied to cuts in the estate tax) would have raised the minimum wage to $7.25/hour. That’s almost $2.50/hour less than what the average Wal-Mart worker makes.

If we are to avoid being called hypocrites on the matter, we might do well to talk more about a ‘livable wage’ than a ‘minimum wage’ that clearly does not make it easy for people to get by with one job. Chicago has taken the lead in this, overriding Mayor Richard Daley’s veto to establish such standards:

Defying Mayor Daley and challenging Wal-Mart and Target to follow through on their threats, a bitterly divided City Council voted Wednesday to require Chicago’s big-box retailers to pay employees a “living wage” of at least $10 an hour and $3 in benefits by 2010.

[…]

The ordinance that will make Chicago the nation’s largest city to mandate wage and benefit standards for retailing giants will be phased in, beginning with mandatory pay of $9.25 an hour and $1.50 in benefits on July 1, 2007, and ending July 1, 2010, with $10 an hour and $3 in benefits. After that, the “living wage” would be raised annually to match the rate of inflation.

It’s hard to say whose numbers are right – the supporters of the ‘living wage’ law in Chicago cited the average salary of a Wal-Mart worker to be $7.70/hour. Nevertheless, it’s clear that this is a move in the right direction – not only increasing the wages required to be paid to retail workers, but also increasing the amount of benefits that are accrued on the job. By separating the two discussions, most Americans won’t be able to distinguish why we criticize Wal-Mart for paying above the minimum wage if we push for an increase in the minimum wage to levels that don’t even match what workers currently make.

Another problem that we face is the public perception of Wal-Mart. At a Wake-Up Walmart rally, former senator John Edwards spoke about the need for consumers to think about where their money was going:

“We want every single consumer in America, every person in America, to know that if they walk into a Wal-Mart, that first of all their tax dollars are subsidizing Wal-Mart employees. Their tax dollars are helping provide health care for Wal-Mart employees, because Wal-Mart’s not doing it. Their tax dollars are going to provide housing and food stamps for Wal-Mart employees,” Mr. Edwards told a crowd of 400 at Hill House. “What is wrong with this picture?”

It’s an honorable ideal – but realistically, the average person doesn’t really give half a damn where their money goes, so long as they are getting a good deal. It’s difficult to compete with Wal-Mart when it has lower prices than its closest competitors. A couple weeks ago at work, CNBC was interviewing people at Wal-Mart about what they thought about the company. They largely had a positive reception to the store, even when the abuses that took place were brought up. In today’s Wall Street Journal, poll findings seem to confirm that Americans seem to enjoy the benefits of Wal-Mart’s low prices:

Polls commissioned by the company suggest it might have popular support on its side. A June poll by RT Strategies, a bipartisan polling firm, found that 62% of voters disapprove of Democratic candidates making Wal-Mart an issue in the election. Among Democrats, 48% disapproved while 34% approved.

A July poll by Strategy One, a research arm of Wal-Mart’s outside public-relations firm, Edelman Public Affairs, found that 64% of Democrats have a favorable opinion of Wal-Mart, with much of the support coming from African-Americans, one of the party’s most loyal voting blocs.

One could question the methodologies that these polls used, given that Wal-Mart commissioned them. However, in a quick scan of the Internet, I haven’t been able to find any real criticism. Additionally, here’s a deeper breakdown of the RT Strategies poll that was conducted:

- 71 percent of Americans believe Wal-Mart is good for consumers while 63 percent of union households hold the same belief

- 58 percent of Americans and 54 percent of union households believe union leaders should make protecting union jobs a higher priority than attacking Wal-Mart

- 60 percent of Americans say the campaign against Wal-Mart is not a good use of union dues and 44 percent of union households agree

- 54 percent of Americans and 42 percent of union households believe the campaign against Wal-Mart makes labor union leaders less relevant to solving the economic challenges facing working families today.

Although union households are less likely to have a favorable image of a very hostile anti-union company, it still seems to suggest that they believe consumers get a good deal. Therein lies our problem – we are focusing on helping the workers of Wal-Mart, who need it greatly – but what affect it has on the consumer, who just wants the cheapest goods around, seems to be very little. Also, regardless of the working conditions, there still seems to be quite a bit of enthusiasm among people to work at Wal-Mart. An excerpt from the Journal recounts what happened when a new shopping center opened near Representative Jesse Jackson, Jr.’s district:

The retailer recently opened a new store near Mr. Jackson’s Chicago district. About 3,000 people applied for the store’s 300 positions. Wal-Mart also hired local minority businesses to do accounting and logistical work for the store.

There’s been a documentary, countless articles, and several interest groups set up to confront Wal-Mart’s misdeeds. But is it best for Democratic politicians to become actively involved, as if it’s a ‘rite of passage’, in a sense? It’s a double-edged sword because we are criticizing a company that, while it may treat its workers poorly, gives undeniable benefits to its consumers – people who are largely in the same class as those who work at the store. The 2004 election showed how difficult it was for the Democratic Party to manage a nuanced position; is it something we should really trust them to do well on when it comes to Wal-Mart? Sure, it may be the easiest proxy to use when it comes to truly assessing how American workers are doing, but it’s a small slice of the working population. What many of us see as a righteous stand against an abusive corporation, many others see as an attack on a company that helps alleviate their living costs through low prices. Senator Evan Bayh had this to say about the company:

“Wal-Mart,” he said, “has become emblematic of the anxiety around the country, and the middle-class squeeze.”

The issue of Wal-Mart, though, could come back to squeeze Democrats if we do not address the issue sensibly. In an election year where the dominant issue is going to be Iraq, is it worth our time to focus our firepower on one chain of stores? I believe that while Democrats can endorse what groups like Wake-up Walmart are doing, there’s no reason they should have to actively campaign – particularly when it could look like we are advocating for the rights of one set of workers but not everyone else.

I think a lot of people have a love/hate relationship with Wal-Mart. They hate everything but the low prices on certain items.

For example, I was recently looking for a salad spinner. Not a major thing, I’ve recently been eating a lot more salad and thought a salad spinner would make the process a bit easier. Anyways, I went to a couple of kitchenware stores and the only ones I could find were 39.99 or more! (Canadian dollars) On the way home, I passed a Wal-Mart and thought I would check, just to see. Sure enough, they had one for 4.99. I’m not poor, but I’m not going to throw my money away. When I can by something there for almost a tenth of the price as a specialty store, I’m going to do it.

Generally though, I try and shop at other stores when possible. For example, we have a chain called the Superstore which I worked at when I was in school. It’s unionized by the UFCW and it was a half-decent place to work. The long-term employees were making close to 20 bucks an hour and I know they’ve had a raise in their latest contract. I don’t feel as bad shopping there knowing that the people working there are making a decent amount of money.

Knowing that people want to shop ethically, but not pay a ton more to do it, promoting locally-run cooperatives is a good strategy where practical. If you can get a bunch of people together to combine their purchasing power, you can get good deals on all sorts of products and not feel bad about giving money to Wal-Mart.

Walmart is cancer capitalism at its most cancerous.

How can you NOT attack it?

Once Walmart has the RFID system in place, it won’t need to bother with employees.

If we would only relax and get injected with tiny microchips, we could march off to the Big Box and automatically turn over our remaining money for all those goodies we need to be really happy.

I leave the political strategy to others, but there are several points raised which need to be addressed.

If you want some independent information about Walmart and would like to comment as well please visit our group blog, we are not affiliated with any pressure groups:

TheWritingOnTheWal.net

That’s the question. And the sad, repugnant horrifying answer is found in the fact that Democrats (and many liberals)even enterain that question.

Workers this week. Gays the next. Immigrants. Blacks. Women. God forbid their rights should get in the way of someone’s electability.

I guess it is just quaint to expect politicians to stand up for something and to make their case for it. Are we electing leaders or prostitutes?

American Families

Ever see how Wal-Mart goes after a toilet paper company, saying it will give them a contract IF they only sell to them. So the company does an overhaul only to be told that a China firm has undercut them by .0008 cents. So Wal-Mart will go with them and the American business falls apart.

Nothing is being manufactured in America nowdays except a few clinging companies and WAR.

War-Mart… coming to a job loss due to outsourcing in your family.

Plus, CHEAP has a price. I wouldn’t own an item made by a child who goes hungry every night.

I completely agree with what you’re saying.

However, most American consumers do not think about where they are buying things from. If it’s cheap, it’s as good as sold.

That’s what I’m trying to find out – what the best way to address the issue of speaking to the consumer is. I don’t feel that Wake-up Walmart and the Democratic politicians are doing that.

How do you reconcile this to the bashing of “big oil” that politicians engage in?

An argument could be made that oil companies have a less direct effect on the price of gasoline than does Walmart on the stuff it sells. After all 80% of the oil supplies are owned by national governments or their state-controlled oil companies.

Politicians don’t seem to have any problem attacking certain firms by name (BP recently and Exxon in the past) why should Walmart be treated differently?

Love ya, psifighter, but this diary makes me sick at heart.

The fact that you pose the question means that Wake-Up Walmart and the Democrats who support it have not yet made their case well enough. And that is important to know.

In you last sentence you say, “it could look like we are advocating for the rights of one set of workers but not everyone else.”

What people fail to realize is that Wal-Mart’s policies effect far more than the workers they employ. Their policies effect workers in other big box and grocery chains. Their policies effect everyone who pays taxes. Their policies effect all the workers of all their suppliers and all the workers of their suppliers’ competitors.

But what distresses me most, as I mentioned in another comment is the assumption that we have to trade ethical, humane values for creativity.

The last word in my last sentence was meant to be electability.

for the voter.

Tell them how much their cheap products are actually costing them because their tax dollars go to support those employed by the largest corporation in the world. We support them with paying out taxes for their healthcare because Wal-Mart won’t.

It’s supporting the destruction of AMERICAN JOBS, and it’s supporting slave labor.

No one should wear a coat that another starved while making.

oh… and NIKE, the big employer in my neighborhood… they all drive fancy cars with their gold swoops on the ass end of their BMW’s and SUVS but guess who MAKES the shoes and clothing.

Americans need to start THINKING about things. Instead of just fatassing it on the couch in front of American Idol.

Our democrats haven’t done shit about the war, wal-mart, healthcare… but it’s not my fault that I at least will continue to bash anything about Wal-Mart.

Buy Locally owned, support your community. Support your neighbor’s family AND YOUR OWN.

(((PSI)))) 🙂

Janet:

If you feel so strongly about Walmart, why not contribute to our blog. There is something to get your blood boiling nearly everyday.

http://thewritingonthewal.net

Looking forward to what you have to say…

My blood pressure is already too much LOL Thank you for the invite though. My good friend here does alot of anti-Wal-Mart activities. We’re fighting one that’s trying to weasel it’s way in to Beaverton, Or.

She has Wal-Mart, I have Lt. Watada and CodePink issues… plus I have two kidlets at home.

I’ve added it on to my favorites and will pass it along to my friends. Thanks!!!

I don’t know where Rubbermade is manufactured, but I am pretty sure that the W-store (we don’t say its name in our house) almost drove them out of business because it wouldn’t meet a certain price point.

I believe a more through review of the issue has been done by Frontline…

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/walmart/

Truthfully, I try to avoid Wal-Mart as much as possible. It so much nicer to shop for groceries at a grocery store, like Hy-Vee.

The true Wal-Mart story is that they squeeze their suppliers/vendors for a lower price. And those suppliers/vendors then squeeze their employees, to lower wages or move their jobs abroad. Just as mentioned by Janet..once the U.S. Co. cannot be squeezed below a foreign supplier..Wal-Mart drops their American supplier/vendor.

Whatever, happen to buying “American”, spend your money where you make it!

I acknowledge all the faults you have listed above. That’s not what I’m trying to get at, though. I’m well aware Walmart has committed various moral and ethical transgressions.

What I’m trying to examine is if the way that the Democratic Party is trying to deal with the company is the best possible way.

Why not, those faults listed make them “fair game” of how the Republicans are cozy with big business and don’t care

about the average worker. Anyway..Wal-Mart for the first time did not post an increased in profit..maybe to many of their customers are getting “hot gas–> there is your next diary.:

http://www.kansascity.com/mld/kansascity/15370193.htm

I think no matter what, the Dems will get spanked on any issue.

We could find Bush in bed with the dead body of ten boys and if the Dems were outraged about it… Rush, Inc would find some way to blame liberals for it

🙂

Dems don’t fight the counter-spin on anything it seems. It does look like they are elitists after poor people just trying to make ends meet… but THAT is what Wal-Mart does to entire communities.

I lived in one that had Kmart and Wal-Mart and it destroys then entire economy of that area.

Right you are Janet. And here in small town, small state Idaho they kill the local businesses. All of the things listed about the W are absolutely worth pounding. They pay different wages in different areas of the country. Here in Idaho it is about $6.50 per hr. So their lying claims about workers wages are just that LIES.

Their grocery prices here are certainly NOT the cheapest here and the non-packaged food items are not the best by a long shot.

They get huge tax breaks and property tax breaks as an “inticement” to come to our state. It puts a tremendous burden on all the other business who just cannot compete. As everyone knows, if you can get the customer in the store you have pretty much got them

I think the MYTH of their low prices is mostly that, although some items are lower than anywhere else.

People with very little spendable income feel they have no place else to go. . .and that is by far the majority of people in low wages Idaho.

But most of all, What wall mart does and gets away with affects every retail and manufacturing business out there and all of their employees, so it is MUCH MUCH a bigger and more important problem than just walmart.

JMHO