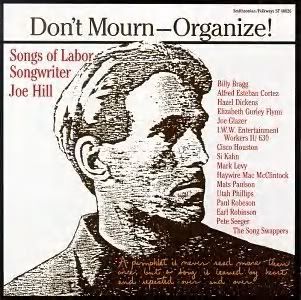

“The music of Joe Hill was a uniting force that captured the spirit of the radical Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) labor movement.

Although he never electronically recorded his songs, Hill’s music was passed from voice-to-voice across the American landscape with certain songs emerging as anthems for struggling bands of men and women seeking to redefine opportunity in this nation at the turn of the last century.

Modern students of music history have identified Hill as one the most influential protest artists in American history, an influence that can be heard in the work of songwriters as diverse as Woody Guthrie and John Lennon.” By Mary Killebrew

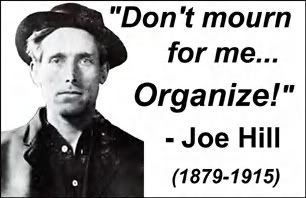

Who Was Joe Hill?

Writer of Protest songs, Union Activist, Martyr for “the Cause?”

A lot of words have been written about Joe Hill. Some of them are true, some of them are myth, some of them are lies and some of them I doubt we will ever know.

He was born Joel Emmanuel Hagglund, in 1879 in Gavle, Sweden. They didn’t have much and they had even less when his father died shortly after Joel’s 8th birthday. The six surviving children in the family (two had died from illness) were sent out to work to support the family. He began his working life in the town rope factory and then as he grew a bit moved on to shoveling coal on a steam engine for a construction company. By the time he was 12 he had contracted a type of tuberculosis that affected his joints and skin.. He underwent several skin operations and also was treated with massive doses of X-rays to control the disease.

After his mother passed away in 1902, Joel and his brother Paul decided to try their luck in America and landed in New York City in October of 1902. They arrived here with nothing and were soon greatly disillusioned to find that the “easy wealth” stories that abounded about America were highly exaggerated at best. He started his working life in the USA cleaning spitoons in a dive of a bar in the worst section of New York for a few pennies a day in wages. He soon saw that this work was not going to see him through and left New York for the Mid-West. Where he wandered and what he did during the next 8 years is not known. Somewhere along his travels he must have run into some sort of trouble or reason to change his name because sometime between 1906 and 1910, he became Joseph Hillstrom.

As he wandered across America doing all manner of low-paying and labor intensive jobs, he met thousands of immigrants just like himself, stuggling to get by as he was and it had quite an impact on him. By the time he was 30 years old he had a pretty hard and cynical view of this new land he had adopted as his home. He felt they were a vast sea of poor captive families at the feet of the small handful of very wealthy and powerful individuals.

“In 1910, as he apparently worked for a period of time on the docks of San Pedro, California, Hillstrom was exposed to the heated rhetoric of a small band of determined labor activists who claimed they had a new vision for the future, and a new method for knocking the mighty off their high horse. The group called themselves the Industrial Workers of the World–and were known by the nickname of “Wobblies.”

The Wobblies were part of an era of social, economic and political uncertainty in the United States and the world. The I.W.W. was a more radical extention of movements challenging the existing order, including Socialists, Progressives and Populists.

The I.W.W. had come to life in Chicago just a few years before Hillstrom’s introduction to the cause. The Wobbly founders were fed-up with marginal, inconsistent success in the nation’s labor movement, and offered a dream for the total transformation of the American economic system, predicated on every man, woman and child joining “One Big Union” to take profits away from the wealthy and place them in the hands of the people who did the actual work.

Hillstrom embraced the ideology of the I.W.W., and soon joined the union and began to recruit members and support fellow Wobblies wherever conflict might surface. In late 1910 he wrote a letter to the I.W.W. newspaper, Industrial Worker, identifying himself as a member of the Portland, Oregon I.W.W. local. The letter denounced the tactics of local police in attacking Wobblies and other workers in the area. In the first documented use of a name that would eventually become known around the world, the letter was signed “Joe Hill.”

By January, 1911 Hill was on the border between California and Mexico, ready to join a brigade of Wobblies determined to aid the forces fighting for the overthrow of the Mexican government. As the revolution wore on south of the border, Hill was reportedly in the border town of Tijuana. Denouncing the role of capitalists in opposing the peasant uprising, Hill urged other Americans to join the fray.

Even with the occasional letter or postcard sending a time stamp on his whereabouts, Hill’s years with the Wobblies are shrouded in contradictory reports, legends and tall tales. Years later he would be reported on the front lines of virtually every major job action involving the I.W.W. between 1909 and 1912. Legend would often have Hill fighting for the Wobblies in a dozen different locations at the same time.

One thing is certain. If Hill was not on the lines in person, he was there in the form of song.” From a PBS Biography found HERE

Joe, as he was now known, had a lifelong love of music and had taught himself to play the piano, guitar and violin. He began crafting a stream of songs with the hope of firing up the poorest workers in America. The songs extolled the virtues of the workers and decried the bosses and scabs. It didn’t take long for his songs to become an important part of the I.W,W.’s Little Red Songbook.

“Hill almost certainly had brushes with the law during this time. Virtually nothing exists on paper to document what, if any, crimes were committed under his name. Wobblies report that Hill was severely beaten by police in Fresno during a labor disturbance. Hill himself would acknowledge doing thirty days in the local San Pedro jail on a trumped-up charge of vagrancy, which he claimed was a masquerade for powerful interests trying to silence him during a longshoreman’s strike. Years later the San Pedro police would paint a different picture when they reported that Hill was actually the prime suspect in the armed robbery of a streetcar, but could not be prosecuted because the assailant wore a mask and could not be positively identified.

Of all the uncertainties surrounding the life of Joe Hill, one of the most perplexing is his decision in 1913 to travel to Utah.

In 1913 Utah had been a state for less than twenty years. Institutions in the state were uneasy in light of the lingering suspicions that existed among some federal authorities to the powerful role of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Better known to non-members as “Mormons,” the church had struggled with federal authority for nearly fifty years over the controversial practice of plural marriage by members. It had been a pitched battle that was not fully settled until 1904, when church leadership issued a strict order prohibiting members from engaging in plural marriage.

Utah had modestly active mining and smelting industries, controlled largely by non-Mormon owners. Church leaders, however, had voiced strong anti-union sentiments throughout recent attempts to organize sectors of the labor force. When it came to the role of the Industrial Workers of the World in Utah, religious differences melted away. Social, economic, political and religious forces voiced opposition to the actions and aims of the Wobblies, and vowed to fight the radicals at every turn.

Some acquaintances claim Joe Hill was merely trying to get through Utah to travel to I.W.W. headquarters in Chicago and meet with Wobbly leader “Big Bill” Haywood to plan a more active role in the Wobblies’ national efforts. Regardless of his intent, Hill arrived in Salt Lake City during the summer of 1913.

He would never leave the state alive.”

PBS Biography

Snip. . .

“On the night of January 10, 1914 two men entered the small grocery store operated by John Morrison near downtown Salt Lake City shortly before 10:00 p.m. Morrison and his son, Arling, were sweeping up and preparing to close the store for the night. At the back of the store, Morrison’s younger son, Merlin, waited for the lights to be turned out so the family could go home.

murder image

Re-enactment of the Morrison shootingTwo gunmen dashed into the store wearing hats and handkerchiefs pulled up to cover their faces. One spotted John Morrison behind the counter, shouted something, and began firing a handgun at the storeowner. Almost immediately, Arling grabbed the family’s revolver and fired at the intruders. In response the masked gunman leveled his weapon at Arling Morrison and fired at least two shots. The invading gunmen then fled the store.

Young Merlin Morrison was the first on the scene. His brother was already dead from multiple gunshot wounds. His father groaned nearby. John Morrison would cling to life for a few minutes, but would die before medical attention could be arranged.

Merlin told police who arrived at the scene that he had been able to glimpse portions of the shootout from the back of the store. He provided vague descriptions of the two men, reported that Arling had shot back, and stated that the lead gunman has clearly shouted “We’ve got you now!” before firing at John Morrison. Police checked the cash register and found the day’s receipts in place in the till.

The police knew John Morrison. He had been a member of the police force for a brief period before turning to what he hoped would be the more bucolic life of grocery store owner. Morrison had complained on several occasions that his time on the force had made him too many enemies who carried a grudge. He feared he would be the victim of a payback when criminals were released from jail. Additionally, police knew that Morrison had already had at least one shootout with armed bandits at his store, seriously wounding one invader in the process. It was Morrision’s old service revolver that his son, Arling, had pulled from the produce bin when the shooting started.

The police quickly reached some preliminary conclusions, and passed them on to reporters who had gathered at the scene from Salt Lake City’s three major daily newspapers. First, they announced that the attack was indeed a payback by someone who knew and disliked Morrison. They pointed to the full cash register as proof that it was not a robbery attempt. They also cited Merlin Morrison’s version of the gunman’s words as proof that the bandits knew Morrison before the attack. The second conclusion reached by police was that Arling Morrison’s single gunshot had found its mark. Although there was no bullet retrieved or blood in the store, apart from the Morrison’s, police said eyewitnesses were convinced that one of the gunmen leaving the store was acting injured. Police also reported that drops of blood were found in the snow approximately one block from the Morrison store.

The next morning, Salt Lake City’s newspapers announced the search for two gunmen who had killed a father and son in a wanton “act of revenge.” PBS Biography

Now things start to get murky. At about 11:30pm that same night, Joe Hill showed up at Dr Frank McHugh’s home clutching his chest. The good Dr. examined him, noting the bullet had passed clear through him without hitting any vital organs, then cleaned and dressed the wound. He had Joe rest on a bed until it could be arranged for a friend to drive him home. Apparently during the exam, a holstered gun dropped from Hill’s clothing. During the drive home, Dr. McHugh’s friend had been asked to stop at a vacant field where Hill, it seems, tossed the gun.

When the good Dr. McHugh read about the murders at the nearby store in Murray, Utah (Salt Lake suburb) the next morning, he called the police department and reported his treatment of Joe Hill’s wounds.

“Murray police units rushed to the Eselius house, stormed up the stairs, and kicked in the door on Joe Hill’s room. Finding him in bed, the police ordered Hill at gunpoint not to move. When he made a reaching motion across the bed, an officer fired. The bullet passed through Hill’s hand, shattering bones. Hill had not been reaching for a weapon, as suspected, but was instead reaching for his pants.

Police did not know they had arrested a significant figure in a radical labor movement. Newspaper coverage of the arrest demonstrated no interest in Joseph Hillstrom’s association with the Industrial Workers of the World. In fact, there was no public connection of the murder suspect to the Wobblies until the eve of his trial. Only then was it noted in local papers that Hillstrom was, in fact, Joe Hill, a radical who had something of a following due to his songs and poetry.

Pleading poverty, Hill acted as his own attorney during a preliminary hearing. Hill offered little resistence as the prosecution produced a dozen witnesses who testified to the circumstantial case against Hill. The prosecution had discarded all of the early police theories about motive for the crimes. Rather than argue revenge against Morrison, the prosecution decided to forego motive almost entirely. Instead they spoke in vague terms of a robbery gone bad. Hill was bound over for trial, held without bail, and informed that the state would seek the death penalty against him.

For his trial, Hill accepted the offer of two young Salt Lake City attorneys to represent him free of charge. Long before a public defenders office existed to provide legal representation for the poor, young attorneys often volunteered to defend the poor in high-profile cases in the hopes of advancing their careers. In the case of Joseph Hillstrom, the defendant and his attorneys soon turned into courtroom combatants.

Midway through the prosecution’s case, Hill dramatically announced he was firing his attorneys because of his belief that they were, in fact, partners with the District Attorney in railroading him for a crime he did not commit. Judge Morris Ritchie refused to excuse the two young attorneys, allowing Hill to take a more active role in his defense. The split was never reconciled, and Hill virtually refused to have anything to do with the trial.

The prosecution’s case boiled down to a series of witnesses, including Merlin Morrison, who testified that Hill bore varying degrees of similarity to one of the gunmen seen entering the Morrison store on January 10, 1914. At least one witness identified the scars on Hill’s face as similar to scars on one of the gunment. In addition, the testimony of Dr. McHugh challenged the jury to conclude that Hill’s gunshot wound was more than mere coincidence.

Throughout the trial, it had been assumed that Hill would take the stand in his own defense, describe the circumstances of his gunshot wound, and perhaps even name the woman he claimed was the reason for his injury. Even the prosecution stated that Hill had to seize the opportunity afforded in the trial to prove his innocence.

In the face of all the expectations, Hill refused to testify.

Some speculated that his was the action of a man of honor who would not dare harm the reputation of a reportedly married woman caught in an embarrassing tryst that led to the shooting. Others speculated that Hill was advised by I.W.W. legal advisors not to testify. The prosecution said Hill did not testify because his alibi would not hold up under scrutiny. The defense attorneys only knew that Hill wouldn’t talk in court.

Rather than open the door to acquittal, the move sealed Hill’s fate. The jury deliberated only a few hours before returning a guilty verdict. Under Utah law Hill was given the option of either being shot to death, or hung at the gallows for his crime.

“I’ll take the shooting,” Hill told the judge. “I’ve been shot a couple times before, and I think I can take it.”

With the death sentence, Hill was transferred to the Utah State Penitentiary to await execution.”

PBS Biography

Immediately the I.W.W. president, “Big Bill” Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn began a nationwide tour speaking at rallies and laying the claim that “Big Business” was to balme for Joe Hill’s conviction. They called on fellow workers to send letters to the judge, the police, the news papers demanding a release of Jo Hill. Hundreds of letters and telegrams and petitions showed up on the desks of Utah’s Govenor, William Spry and President Woodrow Wilson.

When the Swedish ambassador telegraphed Wilson with his conviction that Hill had not received a fair trial, the President asked Spry to delay the execution pending a full review of the case. Seething at the unusual presidential intervention, Spry offered Hill and the ambassador opportunities to produce any compelling evidence that might change the guilty verdict. The ambassador had nothing to offer, and Hill refused to speak. In one message Hill maintained that he had been denied a fair trial, and that in a fair trial he would not have been proven guilty. He maintained that it was not his duty to prove his innocence.

Despite the calls for additional presidential intervention, including a heartfelt pleading from Helen Keller, Wilson was reluctant to do more than he already had. It was only when the convention of the American Federation of Labor telegraphed a demand for action that Wilson, facing a re-election campaign in 1916, again sought to convince Governor Spry to delay the execution. This time Spry, a Republican, adamantly refused to listen to Wilson, a Democrat.

In one of his last messages from his death row cell, Joe Hill sent a telegram to fellow Wobbly “Big Bill” Haywood. The message would emerge as a rallying cry for workers and protestors for generations to come:

“Don’t waste time mourning. Organize!”

Joe Hill was shot to death by a firing squad on the morning of November 19, 1915.

PBS Biography

The speculation continues to this day whether Joe was rightly convicted of a murder he was guilty of, or whether seeing the opportunity to become a martyr for the cause that would rally thousands of workers to the union, he chose to let it be that he would forever be remembered.

While motives are debatable, it is a fact that in death Joe Hill became recognized as a martyr for his cause. The songs he had crafted for the I.W.W. took on greater significance with his execution, and were invoked with a strangely near-religious sentiment in labor strikes and protest settings. Those who shared his views would invoke his name as evidence that conspiracies existed among the powerful elite of the nation, and that a good man had fallen at the hands of Big Business and its government partners.

With the resurgence of union activity in the years after World War One, the name of Joe Hill would be invoked in dozens of labor struggles throughout the nation. His songs were sung as a tribute to the man who had urged the world not to mourn, but to organize. Soon poems and songs of tribute to Joe Hill started to circulate among the groups determined to redesign the workplace and society. One of the most enduring was penned in 1925 by the poet Alfred Hayes:

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

Alive as you and me.

Says I, “But Joe you’re ten years dead,”

“I never died,” says he.The revolution Hill yearned for did not materialize in the nation he adopted back in 1902. Yet the work, words, life and death of Joe Hill remain in the public eye ninety-one years after his execution. In one sense, proving Alfred Hayes a prophet through his poetry.

Joe Hill is still talked about in Union circles today. In those circles the belief is strongly held that he was a martyr for the greater cause, for the Union and its members. I guess only Joe really knows whether he was innocent or guilty.