“Veteran’s Day” 11 November 2006

A review by Cho and Ilona Meagher

A review by Cho and Ilona Meagher

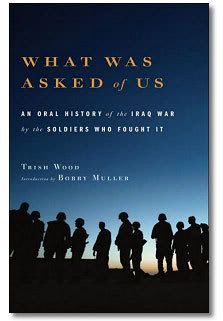

What Was Asked of Us by Trish Wood

(New York: Little Brown and Company, 2006)

"There is also a heroism in telling the unvarnished truth about war" (p. xx).

Listening is a good place to start any dialogue, especially one as controversial and grave as war. "Invite veterans to speak about their experiences in serving the country," said President Bush in a speech at Maryland’s Thomas Wootton High School. "[They] show us the meaning of sacrifice and citizenship, and we should learn from them."

In What Was Asked of Us, author and award-winning investigative reporter Trish Wood lets 29 young men and women who fought in and returned from the Iraq War speak without anyone spinning, packaging, cherry-picking, or pre-digesting their words. Some of the voices are convinced of America’s rightness to be in Iraq; others are less sure. Some are angry; some feel guilt. And chillingly, others admit to missing the adrenaline rush of the fire fights, the "fun" of posing dead bodies for photographs–and even the killing.

Also posted on the ePluribus Media Journal

As with the University of Arizona’s Border Film Project that handed out cameras to ‘Minutemen’ and ‘Crossers’ alike at the Mexican-American border, a more dimensional, more honest picture emerges from the multiple snapshots provided by those actually living within a narrative. And so too, in Wood’s What Was Asked of Us, the ‘ground truth’ rises from the stories these Iraq veterans tell. From their voices, a composite emerges of them, of us, the war, the planners, and of the post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) waiting for a growing many.

The Soldiers

There’s Ken Davis — a fundamentalist who personifies core Christian values, who remembers repeatedly telling his troops: "We only have one shot at making an impression, at showing them we are not like Saddam. We are not these infidels; we’re not these rapists; we are not murderers. We are American soldiers, and we have integrity and honor." (p. 90).

Styled the "preacher," Davis is the one to whom Charles Graner, a guard eventually convicted of prisoner abuse, asks, "They’re making me do things that I feel are morally and ethically wrong. What should I do?" (p. 91). Davis relates how he reported the Abu Ghraib outrages to his superior, significantly a few weeks before whistleblower Joseph Darby handed investigators the photo CD of Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse on January 13, 2004.

Davis concludes:

What makes us always right? That’s what I always ask myself: America, what makes us always right? In the Christian tradition, it is very clear that if you’ve sinned, acknowledge your sin. And even if that’s not enough, you go to your brothers and your sisters, and they help lift you up. But if you will not admit your sin, God will shine his light on it and show you. Someone’s got to stand up and take the blame for this war and say. . . we’re sorry (p. 99).

Like Davis, some of the other soldiers are beacons of hope and honor.

Alan King reflects: "I don’t think I’ve ever lost hope, even to this day. . . .The fact that these guys still line up at police stations, even though they are getting blown up by suicide bombers, tells you they want it to work" (p. 64). Joseph Powers, desperate to make a positive contribution, tells of his work with the orphanages — that is, until work in Iraq had to stop because of the danger the presence of the Americans drew to the children. Undeterred, Powers now works with Iraqi orphans through the War Kids Relief foundation stateside (p. 258).

These are the leaders, those whom any community would look up to and revere. Others are average guys caught up in doing the best possible in the nightmare world of insurgency. And still other voices are disturbing and remind us that all kinds of soldiers fight our wars, even the psychologically needy and the berserkers.

Sometimes if we captured one of them that had been shooting at us, if we caught him with an AK and he surrendered, we’d bring him back to the combat outpost. Sometimes they didn’t make it that far, you know? (p. 158)

US

As readers, we may recoil from such admissions of battlefield executions, but who are we, from the cushy realities of our civilian lives, to judge these men and women? For, as the composite emerges, it becomes clear that we too are complicit.

According to a poll reported by CNN, only 37 percent of 18 -24 year old Americans polled could even find Iraq on a map. Only 12 percent could find Afghanistan. Troop reaction to this ignorance is swift and unflinching:

"It really pisses me off when people don’t have an understanding of Jalal Talabani. Who’s the prime minister of Iraq? Who’s the president of Iraq? When did we assault Falluja? A lot of people died during those times." — Benjamin Flanders, New Hampshire Army National Guard (p. 238).

Most of the soldiers presented in What Was Asked of Us express feeling estranged from ‘normal’ life. "Supporting the war is not hip right now," says one. "It’s not the thing to do right now to support the troops" (p. 152). But unlike the post-Vietnam era, when returning vets felt alienated from those questioning the war, most of today’s Iraq War veterans interviewed by Wood speak with wry distaste for those "supporters" who mindlessly regurgitate war slogans. "They don’t invest themselves in the real issues of the war," says Flanders. " Why did we get over there? When are we going to return? What is happening? How many soldiers have died?" He challenges us: "If I were to ask you, ballpark — how many soldiers have died in Iraq . . . well, do you actually know?" (p. 296)

Dominick King, a Marine who served in Falluja during the second taking of the city, provides another example of the impatience some troops have for our simplistic slogans on war and freedom:

"When we got back from Iraq, me and my friend Tabor were in the car driving to Dunkin Donuts or something in the morning, and we were at the stop sign with a car in front of us saying, ‘Freedom Is Not Free,’ and he just looks at me. He goes, ‘Can you believe this? Freedom’s not free, what has he paid?’ " (pp. 230-231)

How society thinks about the war — or doesn’t — impacts the way its participants ultimately deal with their involvement. Ambiguous wars like Iraq complicate this process.

The War

In What Was Asked of Us, Wood hands a figurative microphone over to the men and women on ‘the street,’ so we get their view, unruly and unfiltered [view the book’s video intro]. There is no news anchor pre-digesting the war for us into a tidy, uniform, consistent message.

In What Was Asked of Us, Wood hands a figurative microphone over to the men and women on ‘the street,’ so we get their view, unruly and unfiltered [view the book’s video intro]. There is no news anchor pre-digesting the war for us into a tidy, uniform, consistent message.

Instead, we, the readers, must do our own chewing. We hear from the individuals — from each and every one of 29 soldiers interviewed for the book — what they saw, what images riveted their attention, the harsh sounds they cannot forget, the chilling refrains.

- The splattered brain and bits of skull on the inside of a friend’s helmet;

- The small girl’s foot, still clad in its pink sandal, alone in the street after a suicide blast;

- The body parts, large, small, microscopic;

- The rescue of the upper torso of a blast survivor, a corpsman following behind, separately carrying the legs;

- The smell of burning flesh;

- The pink explosion of dust, colored from the blood of those caught in a Falluja firefight;

- The pounding of drowning men on the door of the submerged tank.

These men and women do not make their memories pretty for our consumption, and in their halting words and repetition, we can sense the depth of the horror that even now their subconscious won’t let go:

- "You don’t want to look at your friend who’s just been shot. You know, it’s sort of a hard thing to digest … I didn’t want to look at him … You know, you just … but once you see it, I mean … I mean, it’s not a good expression on their face." (pp. 226-227).

- "I pulled the poncho liner off him, and his head was missing. He just had half — he just had a quarter of it where the hair was and that’s what was showing" (p. 167).

- "By that time, you know — everyone — everyone in the crew except for two died, drowned. … I heard the pounding. … They were pounding on the side of the tank. You could hear them pounding on the doors" (p. 245).

- "There was one little kid that was — his whole family, mother and father, sister — they were all killed, and he was all by himself. I kind of … That takes a toll too. Seeing stuff like that, especially little kids, kind of … It bothers you. It takes a toll" (p. 12).

Unlike the 63% of Americans polled who couldn’t find Iraq on a map, those who finish this book will be intimate with the names of Iraq towns, provinces and the horrific battles that took place in them: Tall Afar, Kirkuk, Nasiriya, Baquba, Samarra, Karbala. Falluja. Readers will experience firefights at ground level, through the soldiers’ eyes: hand-to-hand combat in cemeteries, in suburban streets, on the banks of the Tigris, the Euphrates and in the scorching desert.

From their stories, it’s clear that there are two parts to this war: The successful invasion followed by the disastrous FUBAR (F*** Up Beyond All Recognition) aftermath. The soldiers’ perception of the war and their role in it is colored by when they served. And those who served multiple tours provide a perspective on how the US’s presence and the Iraqi’s reception of it disintegrated over the 3 and a half years our forces have occupied Iraq.

That progression surfaces slowly as we read through the oral histories organized in a rough chronology. Thomas Smith who served in the initial invasion from March to July 2003 and fought through to Baghdad says "I don’t think it’s for no reason. I think we did a good thing" (p. 14). Adrian Cavazos who served roughly the same time period, from March to August 2003, concludes " if I’m going to die, let me do it serving my country or doing something heroic, something where they can say, He died doing something for someone else, not something selfish or not in some freak accident" (p. 36).

But those who served later often had a different view.

"How many insurgents were killed in Falluja? I don’t know," says Garett Reppenhagen, who served as a sniper in Baquba, Iraq, beginning in February 2004. "The people that we were killing were farmers from the local area. If they had a thousand dollars for a plane ticket to come to America, they wouldn’t come here and terrorize anybody. They’d feed their children." (p.181) or in Jonathan Powers’ question, "Are these kids we’ve been ignoring the next generation of insurgents? There’s 3.5 million kids out of school right now in Iraq and there’s nothing to engage them" (p. 257).

" Any war is hell, but, I mean, a meaningless one is worse." — Joseph Hatcher, served in Iraq with the 4th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division (p. 135)

The War Planners

In reading the words of these men and women [hear their voices at Wood’s highly interactive website], the disconnect between their ground truth and the war the Pentagon thought it was fighting is bruisingly clear. As Jonathon Powers puts it, "It’s not Iraq necessarily that drives the younger officers like me out. It’s the way this war has been handled within the Pentagon" (p. 102).

But to the officers among those Wood interviewed, it was clear that the war’s main ‘planners’ were out of touch with the war reality on the ground. Much has been written about the civilians in charge, those back in Washington who knew nothing of fire fights, hand-to-hand combats or counter insurgency operations. [With news of the resignation of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in the wake of the 2006 Midterm Elections, it’s unclear what direction the Pentagon’s war planning will now take.]

But to the officers among those Wood interviewed, it was clear that the war’s main ‘planners’ were out of touch with the war reality on the ground. Much has been written about the civilians in charge, those back in Washington who knew nothing of fire fights, hand-to-hand combats or counter insurgency operations. [With news of the resignation of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in the wake of the 2006 Midterm Elections, it’s unclear what direction the Pentagon’s war planning will now take.]

Although many of these voices compel our respect, Alan King stands out as what an American military man, in the tradition of the greatest generation’s troops who fought in World War II, should be. No nonsense. Fair. Fearless. Thorough. A leader who understood the intricacies of counter insurgency. "We started getting a lot more respect because I was willing to take the same risks that the Iraqis had to take" (p. 56). But Alan King also relates:

On April 8, 2003, "[Colonel] Jack Sterling came up and said "I just got off the phone with headquarters, and they don’t have a security or reconstruction plan to implement."

….snip ….

"In my personal pre-war planning for my unit, when I asked for this phase of reconstruction plan, I was told that there was one and I would get it when I needed it".

… snip …

"I learned later a plan had been drawn up by the State Department, sort of a government-in-a-box. Never was any of it implemented.

…snip…

There was a plan. Tom Warwick out of the State Department had the Future of Iraq Project, but we never got it" (p. 57).

In April 2006, George Packer’s article for The New Yorker, Letter from Iraq: The Lesson of Tal Afar details Col McMaster’s successful counterinsurgency operation, the same operation that Combat and Operational Stress Control Officer in Charge, Maria Kimble, describes in the closing pages of Wood’s book.

Early in The New Yorker article, Packer suggests that "the story of Tal Afar is not so simple. The effort came after numerous failures, and very late in the war — perhaps too late. And the operation succeeded despite an absence of guidance from senior civilian and military leaders in Washington. The soldiers who worked to secure Tal Afar, were, in a sense, rebels against an incoherent strategy that has brought the American project in Iraq to the brink of defeat." (p. 50). The New Yorker, April 10, 2006)

Although Packer goes on to describe the difficulties of counterinsurgency work, Bradley gunner Jason Neely puts it most succinctly in What Was Asked of Us: "you don’t send a fucking outfit that is supposed to dehumanize others and turn them into targets and kill them, and then fucking ask them to shake hands and stuff with the people they’ve been killing" (p. 46).

PTSD

So, as the reader soon learns reading through these necessary accounts of our returning troops, war alters the course of everything it touches. As successful as the Tall Afar operation may have been, psych specialist Maria Kimble reveals for us its raw emotion by remembering the trauma reaction she and one unit had after losing a mate to an enemy sniper:

"The soldiers who carried the soldier into camp were all distraught, very emotional," she said. "They were crying, bawling, wailing, and asking things like, ‘Why, why him?’ Immediately I just felt helpless, seeing all these male soldiers just breaking down" (p. 286).

As 2004 turned into 2005, troops found their duties increasingly included having to clean up remains of suicide-bombed areas, some containing as many as 30 dead bodies. "It’s extremely traumatic," Kimble says.

In addition to the nearly 3,000 killed in action in Iraq, 20,000+ have returned home with polytraumatic injuries, altering bodies and lives and dreams forever. [The ‘signature injury’ of the Iraq War is traumatic brain injury (TBI) as a result of this war’s Molotov cocktail: the improvised explosive device (IED)] At least 38,000 are being treated for psychological injuries by the Veterans Administration. All told, a full 86,000+ Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) vets have been granted VA disability, with another 30,000+ claims pending review.

Although most of our troops will return home and successfully process their war experience, all will find they have changed in one way or another. Some will have more difficulty and may find their combat stress evolving into post-traumatic stress disorder. Known over the years as nostalgia, soldier’s heart, shell shock, or post-Vietnam syndrome, war trauma is as old as war itself. Returning warriors of all eras have had to find ways to live with what was seen and done during conflict. They need to make peace with those who sent them to war. They also have to find their rhythm and place again among community, employers and family.

As war voyeurs on the sidelines, war even changes us.

"America might have to change before I can change," says Garett Reppenhagen, a cavalry scout and sniper. (p. 293) He tells of how the military and the Iraq War tested him — and disgusted him. The black humor and cruelty — sometimes even his own — the troops directed at the Iraqis they were sent to liberate weighed heavy on him.

Reppenhagen tells us: "I could have been a conscientious objector and bowed out. I could have gone to prison. I could have run away," he said. "You could take the harder road. But I was a coward" (p. 293).

He served in Iraq during an explosive period, arriving just two months before one of the bloodiest months of the war, April 2004. He was there during the kidnapping and brutal public execution of four contractors in Falluja. He was in Iraq during the second taking of the city in November of 2004. And he was in-country during the Abu Ghraib scandal, which he says hurt their collective effort:

In the first Gulf War, hundreds of Iraqi soldiers just laid down their arms and joined the American side. They surrendered. That’s not happening anymore. They’re fighting to the death. No Iraqi, no insurgent, wants to be captured by American forces now because they envision themselves in Abu Ghraib (p. 192).

And on and on these accounts and stories go: swirls of oral history rising up from a crackling fire expertly built by Wood.

Iraq War vet and founder of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA), Paul Rieckhoff, when asked at a panel discussion on war and veterans’ issues what Americans can do to support the troops, answered, "Seek out the experience of Iraq." Author Trish Wood provides just the text to make that possible.

The Stories They Tell Us

What Was Asked of Us hearkens back to two Vietnam era classics.

The lesser-known of the two (though now a standard college literature-course text), The Things that They Carried, Tim O’Brian’s novella of Private Cacciato going in-country, offers a glimpse into the world of the Vietnam conflict through O’Brian’s catalogue of what Cacaccio carried on his back, in his head, and in his arms. Trish Wood, in her ‘Acknowledgements,’ points to the other war classic: Everything We Had: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Thirty Three American Soldiers Who Fought, compiled by Al Santoli.

What these Vietnam-era books provide is the answer to that age-old question: "What was the war really like?" Truth surfaces not from a single point of view, but multiple voices providing a thousand different details that allow us a glimpse, from the safety of our reading chairs, of war chaos on the ground and in the confusing thick. Wood continues that tradition and lets these courageous voices tell us what we asked them to endure for country and flag.

About the Authors:

Cho is a writer, editor and board member of ePluribus Media.

Ilona Meagher is an activist and citizen journalist with ePluribus Media, as well as editor of PTSD Combat: Winning the War Within. Her collaboration with ePluribus Media has resulted in the PTSD Timeline — a database of reported OEF/OIF PTSD incidents — as well as the 3-part series Blaming the Veteran: The Politics of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and The Corroding Effect. A journalism student at Northern Illinois University, Ilona is currently putting the finishing touches on her upcoming book, Moving a Nation to Care: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and America’s

Returning Troops.

Photo Credits: Photograph of Lieutenant Colonel Alan King by staff Sergeant Kevin Bell; Photograph of Doc Paul Rodriguez courtesy of Paul Rodriguez

ePluribus Contributors: avahome, aaron barlow, roxy

Also posted on the ePluribus Media Journal

Buy this book…

If you like what ePMedia’s been doing with research, reviews and interviews, please consider donating to help with our efforts.