December 12 is the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Here’s a news story from the Houston Chronicle about today’s festivities: Mexicans gather to honor the Virgin of Guadalupe on annual holiday. You can read the gist of the story of the Virgin of Guadalupe’s appearance in 1531 to Juan Diego in this homily, given at the University of San Diego in the year 2000, tells the gist of the story.

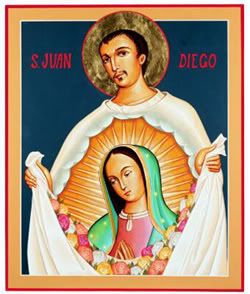

…an elderly Indian man named Chuauhtlatoczin [“Juan Diego” in Spanish] had a vision of Mary, the mother of Jesus, at Tepeyac, a squalid Indian village outside of Mexico City. Mary directed Juan Diego to tell the bishop to build the church in Tepeyac. The Spanish Bishop, however, dismissed the Indian’s tale as mere superstition — he was, after all, an Indian — but then, to humor Juan Diego, he insisted that he bring some sort of proof, if he wanted to be taken seriously. So, three days later, the Virgin Mary appeared again and told Juan Diego to pick the exquisitely beautiful roses that had miraculously bloomed amidst December snows, and take them as a sign to the Bishop. When the Indian opened his poncho to present the roses to the Bishop, the flowers poured out from his poncho to reveal an image of the Virgin Mary painted on the inside of the poncho. That image hangs today in the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City and is venerated by thousands of pilgrims from all over the world.

While I was raised Catholic, I don’t remember learning this story, or if I did, it didn’t really register. Maybe that is because of the “otherness” of the characters involved. Mary of Nazarath, I now know, certainly was not blond and blue-eyed, but as a blond, blue-eyed child, that depiction seemed normal and familiar.

I only came to really read and ponder the story as an adult, having been officially received into the Episcopal church, and felt very much at home in my new church. But it was lacked any iconography of Mary, so I turned to other sources to feed that longing. The writing of Kathleen Norris, in particular, helped me come to terms with the significance of Mary from a more modern, feminist perspective than I had encountered in the past, and also introduced me to the story of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Here is an excerpt of her writing on the subject:

In a recent essay the writer Rugen Martinez lovingly articulates the paradoxes that enliven his sense of the officially sanctioned Mary of church doctrine, and, to borrow his phrase, the “Undocumented Virgin” of personal experience and legend, folktale, and myth. I should probably take this opportunity to make an aside and state that by “myth” I mean a story that you know must be true the first time you hear it. Or, in the words of a five-year-old child, as related by Gertrude Mueller Nelson in her recent Jungian interpretation of fairy tales and Marian theology, Here All Dwell Free, a myth is a story that isn’t true on the outside, only on the inside.

Juan Diego was declared a saint by Pope John Paul II back in 2002, and I recall hearing news stories that there were doubts about the authenticity of the potential saint’s story. I remember easily accepting the notion that the story was “used” as something like a marketing strategy to help convert the native people to Catholicism. And that may indeed be part of the truth. But it’s not all of it. Kathleen Norris writes:

Mary’s love and pity for her children seems to be what people treasure most about her, and what helps her to serve as a bridge between cultures. One great example of this took place in 1531, when the Virgin Mary appeared to an Indian peasant named Juan Diego on the mountain of Tepayac, in Mexico, leaving behind a cloak, a tilma, imprinted with her image. The image has been immortalized as Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Mexican-American theologian Virgilio Elizondo argues, in The Future is Mestizo, that the significance of this image today is that Mary appeared as a “mestiza,” or person of mixed race, a symbol of the union of the indigenous Aztec and Spanish invader. What was, and still is, the scandal of miscegenation was given a holy face and name. As a Protestant I’ll say it all sounds suspiciously biblical to me, recalling the scandal of the Incarnation itself, the mixing together of human and divine in a young, unmarried woman.

I’m getting used to the idea that nothing is as black and white as it first appears–indeed, to welcome and expect that. Here is another meditation on the meaning of the Virgin of Guadalupe, from Social Edge. Will Braun writes, in part:

As immigrant peoples in the Americas –or Turtle Island, as many indigenous people know it– we live on ill-gotten land. Our homes and churches stand on land once home to others. Our spiritual histories must address this reality with honesty, grace, and compassion.

When I look at my postcard version of Our Lady of Guadalupe set beside my bed –as I often do– I see a quiet and compelling invitation to redeem the historical legacy of colonialism in our lands and in our hearts. I let the image sink in. I let it inform my attitude to history and indigenous people, inspiring me to be as much like Our Lady of Guadalupe in posture and tone, and as little like the messianic conquistadors as possible.