Crossposted from Left Toon Lane, Bilerico Project & My Left Wing

click to enlarge

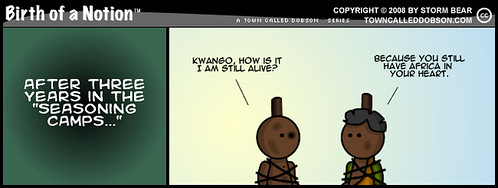

On reaching the Americas the slaver ship crews prepared the Africans for sale. They washed, shaved and rubbed them with palm oil to disguise sores and wounds caused by conditions on board. The captains usually sold their captives directly to planters or specialized wholesalers by auction. Families who had managed to stay together were now often broken up. Bonds formed during the voyage were also broken.

Many slaves shipped directly to North America bypassed this process; however most slaves (destined for island or South American plantations) were likely to be put through this ordeal. The slaves were tortured for the purpose of “breaking” them (like the practice of breaking horses) and conditioning them to their new lot in life. Jamaica held one of the most notorious of these camps.

Immediately owners and their overseers sought to obliterate the identities of their newly acquired slaves, to break their wills and sever any bonds with the past. They forced Africans to adapt to new working and living conditions, to learn a new language and adopt new customs. They called this process ‘seasoning’ and it could last two or three years.

For Africans, weakened by the trauma of the voyage, the brutality of this process was overwhelming. Many died or committed suicide. Others resisted and were punished. The rest found ways of appearing to conform which still preserved their dignity.

Most of the Africans brought into North America prior to 1740 came by way of the West Indies. The most valuable slaves were those born in the Americas–known as Creole slaves, and the least valuable were those directly from Africa. Traders tried to present the enslaved African as being as much like a Creole slave as possible in look and behavior. The process began with the sale itself. Although no standard applied for everywhere in the Americas, the most experienced slavers usually cleaned up the Africans by shaving all the hair from their bodies, washing them with water, and oiling them down with palm oil. The about-to-be-sold slave was also fed often but in small amounts for a few days prior to the sale, trained not to resist having all parts of their bodies examined–especially their reproductive organs, and sometimes allotted a little rum to liven their spirits. In the West Indies, traders might put those slaves destined for the American South into sugar plantation work gangs for a few weeks labor to break them in to the routine. After 1740, when the demand for slave labor was highest, most enslaved people sold into the American South came directly from Africa, and they had to be seasoned by their American owners.

Already branded in Africa with the traders mark, they might be branded again with the mark of the new owner. They also would receive new names–usually Christian ones, or names from Classical Rome and Greece–such as Jupiter or Plato, or African-sounding names–like Quack (which was derived from the African word Quaco, meaning a male born on Wednesday) or Squash (which probably came from the word Quashee, meaning a female born on Sunday). Usually older slaves would be put in charge of the seasoning process, teaching the newly purchased enslaved African how to work in gangs, how to conduct themselves, and how to adapt what they knew in Africa to the new environment of slavery.

The following is a transcript from a slave named Olaudah Equiano in 1789. This is part of the Hanover Historical Text Project

We were not many days in the merchant’s custody before we were sold after their usual manner, which is this: On a signal given (as the beat of a drum), the buyers rush at once into the yard where the slaves are confined, and make choice of that parcel they like best. The noise and clamour with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the countenances of the buyers serve not a little to increase the apprehensions of the terrified Africans, who may well be supposed to consider them as the ministers of that destruction to which they think themselves devoted. In this manner, without scruple, are relations and friends separated, most of them never to see each other again. I remember in the vessel in which I was brought over, in the men’s apartment, there were several brothers, who, in the sale, were sold in different lots; and it was very moving on this occasion to see and hear their cries at parting.

O, ye nominal Christians! might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God, who says unto you, Do unto all men as you would men should do unto you? Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends to toil for your luxury and lust of gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice? Are the dearest friends and relations, now rendered more dear by their separation from their kindred, still to be parted from each other, and thus prevented from cheering the gloom of slavery with the small comfort of being together and mingling their sufferings and sorrows? Why are parents to lose their children, brothers their sisters, or husbands their wives? Surely this is a new refinement in cruelty, which, while it has no advantage to atone for it, thus aggravates distress, and adds fresh horrors even to the wretchedness of slavery.

Disclaimer:

When I went to school, we were never taught Black History. We never learned about the Black leaders, the long, agonizing history that brought most Blacks to America. Those atrocities were glossed over in favor of mindlessly boring topics like the X Y Z Affair.

This series of cartoons will review Black history as told from a Black mother to an interracial child. This series will be ugly, course, horrific and truthful. I will mostly abandon the commentary for an article on Black history.

This series is not about Obama or Hillary. I want to you to try to imagine how Black families tell their children of the atrocities their ancestors, all of them, suffered because of the color of their skin. Try to imagine how Black families counsel their children when someone calls them “nigger” for the first time. Can you imagine the bone crushing emotion that must well up? Can you imagine the agony, frustration and anger?

Can you imagine being the Black preacher who tries to paint a picture of a just God every Sunday? Especially in a country that claims where the notion of racism is a thing of the past, the job is difficult.

These strips may at times be entertaining and sometimes they may not – mostly not.

I don’t want you to laugh so hard you cry, I want you to cry so hard you do something about it.