Crossposted from Left Toon Lane, Bilerico Project & My Left Wing

click to enlarge

From Wikipedia:

The second Klan rose in response to urbanization and industrialization, massive immigration from eastern and southern Europe, the Great Migration of African Americans to the North, and the migration of African Americans and whites from rural areas to Southern cities. The Klan grew most in cities which had high growth rates between 1910 and 1930, such as Detroit, Memphis, Dayton, Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston.

Its growth was also affected by mobilization for WWI and postwar tensions, especially in the cities where strangers came up against each other more often. Southern whites resented the arming of black soldiers. Black veterans did not want to go back to second class status. This Klan modeled itself after other fraternal organizations created in the early decades of the 20th century. Organizers signed up hundreds of new members, who paid initiation fees and bought KKK costumes. The organizer kept half the money and sent the rest to state or national officials. When the organizer was done with an area, he organized a huge rally, often with burning crosses and perhaps presenting a Bible to a local Protestant minister. He then left town with the money. The local units operated like many fraternal organizations and occasionally brought in speakers. State and national officials had little or no control over the locals and rarely attempted to forge political activist groups. Stanley Horn, a Southern historian sympathetic to the first Klan, was careful in an oral interview to distinguish it from the later “spurious Ku Klux organization which was in ill-repute — and, of course, had no connection whatsoever with the Klan of Reconstruction days.”

The accumulating social tensions of rapid change were sparked by events in 1915:

* The film The Birth of a Nation was released, mythologizing and glorifying the first Klan.

* Leo Frank, a Jewish man accused of the rape and murder of a young white girl named Mary Phagan, was tried, convicted and lynched near Atlanta against a backdrop of media frenzy.

* The second Ku Klux Klan was founded in Atlanta with a new anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic agenda. The bulk of the founders were from an Atlanta-area organization calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan that had organized around the Frank trial. The new organization emulated the fictionalized version of the Klan presented in The Birth of a Nation.

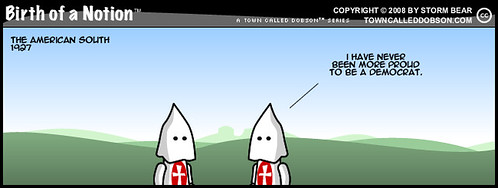

Director D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation glorified the original Klan. His film was based on the book and play The Clansman and the book The Leopard’s Spots, both by Thomas Dixon. Dixon said his purpose was “to revolutionize northern sentiment by a presentation of history that would transform every man in my audience into a good Democrat!” The film created a nationwide Klan craze. At the official premier in Atlanta, members of the Klan rode up and down the street in front of the theater.

Much of the modern Klan’s iconography, including the standardized white costume and the lighted cross, are derived from the film. Its imagery was based on Dixon’s romanticized concept of old Scotland, as portrayed in the novels and poetry of Sir Walter Scott. The film’s influence and popularity were enhanced by a widely reported endorsement by historian and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

he Birth of a Nation included extensive quotations from Woodrow Wilson’s History of the American People, as if to give it a stronger basis. On seeing the film in a special White House screening, Wilson allegedly said, “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Given Wilson’s views on race and the Klan, his statement was taken as supportive of the film. In later correspondence with Griffith, Wilson confirmed his enthusiasm. Wilson’s remarks immediately became controversial. Wilson tried to remain aloof, but finally, on April 30, he issued a non-denial denial. Historian Arthur Link quotes Wilson’s aide, Joseph Tumulty, who said, “the President was entirely unaware of the nature of the play before it was presented and at no time has expressed his approbation of it.”

Another event that influenced the Klan was sensational coverage of the trial, conviction and lynching of a Jewish factory manager from Atlanta named Leo Frank. In lurid newspaper accounts, Frank was accused of the rape and murder of Mary Phagan, a girl employed at his factory.

After a trial in Georgia in which a mob daily surrounded the courtroom, Frank was convicted. Because of the armed mob, the judge asked Frank and his counsel to stay away when the verdict was announced. Frank’s appeals failed. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes dissented from other justices and condemned the mob’s intimidation of the jury as the court’s failing to provide due process to the defendant. After the governor commuted Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment, a mob calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan kidnapped Frank from prison and lynched him.

The Frank trial was used skillfully by Georgia politician and publisher Thomas E. Watson, the editor for The Jeffersonian magazine. He was a leader in recreating the Klan and was later elected to the U.S. Senate. The new Klan was inaugurated in 1915 at a meeting led by William J. Simmons on top of Stone Mountain. A few aging members of the original Klan attended, along with members of the self-named Knights of Mary Phagan.

Simmons claimed to have been inspired by the original Klan’s “Prescripts,” written in 1867 by Confederate veteran George Gordon to try to create a national organization. These were never adopted by the Klan, however. The Prescript stated the Klan’s purposes in idealistic terms, hiding the fact that they committed vigilante violence and murder from behind masks.

“The Klan’s resurgence in the 1920s partially stemmed from the extreme militant wing of the temperance movement. In Arkansas, as elsewhere, the newly formed Ku Klux Klan marked bootleggers as one of the groups that needed to be purged from a morally upright community. In 1922, 200 Klansmen torched saloons that had sprung up in Union County in the wake of the oil discovery boom. The national Klan office ended up in Dallas, Texas, but Little Rock was the home of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan. The first head of this female auxiliary was a former president of the Arkansas WCTU.”

In 1921, the Klan arrived in Oregon from central California and established the state’s first klavern in Medford. In a state with one of the country’s highest percentages of white residents, the Klan attracted up to 14,000 members and established 58 klaverns by the end of 1922. Given small population of non-white minorities outside Portland, the Oregon Klan directed attention almost exclusively against Catholics, who numbered about 8% of the population. In 1922, the Masonic Grand Lodge of Oregon sponsored a bill to require all school-age children to attend public schools. With support of the Klan and Democrat Governor Walter M. Pierce, endorsed by the Klan, the Compulsory Education Law was passed with a majority of votes. Its primary purpose was to shut down Catholic schools in Oregon, but it also affected other private and military schools. It was challenged in court and struck down by the United States Supreme Court Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) before it went into effect.

One historian contends that the KKK’s “support for Prohibition represented the single most important bond between Klansmen throughout the nation.” Membership in the Klan and other prohibition groups overlapped, and they often coordinated activities. For example, Edward Young Clarke, a top leader of the Klan, raised funds for both the Klan and the Anti-Saloon League. A man with his own demons, Clarke was indicted in 1923 for violations of the Mann Act.

A significant characteristic of the second Klan was that it was an organization based in urban areas, reflecting the major shifts of population to cities in both the North and the South. In Michigan, for instance, 40,000 members lived in Detroit, where they made up more than half of the state’s membership. Most Klansmen were lower to middle-class whites who were trying to protect their jobs and housing from the waves of newcomers to the industrial cities: immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, who tended to be Catholic and Jewish in numbers higher than earlier groups of immigrants; and black and white migrants from the South. As new populations poured into cities, rapidly changing neighborhoods created social tensions. Because of the rapid pace of population growth in industrializing cities such as Detroit and Chicago, the Klan grew rapidly in the U.S. Midwest. The Klan also grew in booming Southern cities such as Dallas and Houston.

For some states, historians have obtained membership rosters of some local units and matched the names against city directory and local records to create statistical profiles of the membership. Big city newspapers were often hostile and ridiculed Klansmen as ignorant farmers. Detailed analysis from Indiana showed the rural stereotype was false for that state:

Indiana’s Klansmen represented a wide cross section of society: they were not disproportionately urban or rural, nor were they significantly more or less likely than other members of society to be from the working class, middle class, or professional ranks. Klansmen were Protestants, of course, but they cannot be described exclusively or even predominantly as fundamentalists. In reality, their religious affiliations mirrored the whole of white Protestant society, including those who did not belong to any church.

The Klan attracted people but did not hold most. Membership turned over rapidly as people found it was not the group they wanted. Millions joined, and at its peak in the 1920s, the organization included about 15% of the nation’s eligible population. Lessening of social tensions contributed to decline.

The Klan attracted people but did not hold most. Membership turned over rapidly as people found it was not the group they wanted. Millions joined, and at its peak in the 1920s, the organization included about 15% of the nation’s eligible population. Lessening of social tensions contributed to decline.

In reaction to social changes, the Klan adopted anti-Jewish, anti-Catholic, anti-Communist and anti-immigrant slants. The social unrest of the postwar period included labor strikes over low wages and working conditions in many industrial cities, often led by immigrants, who also organized unions. Klan members worried about labor organizers and socialist leanings of some of the immigrants, which added to the tensions. They also resented upwardly mobile ethnic Catholics. At the same time, in cities Klan members were themselves working in industrial environments and often struggled with working conditions.

Klan groups lynched and murdered Black soldiers returning from World War I while they were still in military uniforms. The Klan warned Blacks that they must respect the rights of the white race “in whose country they are permitted to reside.” The number of lynchings escalated, and from 1918 to 1927, 416 African Americans were killed, mostly in the South.

In Florida, when two black men attempted to vote in November 1920 in Ocoee, Orange County, the Klan attacked the black community. In the ensuing violence, six black residents and two whites were killed, and twenty five black homes, two churches, and a fraternal lodge were destroyed.

Although Klan members were concentrated in the South, Midwest and west, there were some members in New England, too. Klan members torched an African American school in Scituate, Rhode Island.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a violent and zealous faction of the Klan called the Black Legion was active in the Midwestern U.S.. The Legion wore black uniforms and targeted and assassinated communists and socialists.

In southern cities such as Birmingham, Alabama, Klan members kept control of access to the better-paying industrial jobs but opposed unions. During the 1930s and 1940s, Klan leaders urged members to disrupt the Congress of Industrial Organizations(CIO), which advocated industrial unions and was open to African-American members. With access to dynamite and skills from their jobs in mining and steel, in the late 1940s some Klan members in Birmingham began using bombings to intimidate upwardly mobile blacks who moved into middle-class neighborhoods. “By mid-1949, there were so many charred house carcasses that the area [College Hills] was informally named Dynamite Hill.” Independent Klan groups remained active in Birmingham and were deeply engaged in violent opposition to the Civil Rights Movement.

The Klan had major political influence in several states and was influential mostly in the center of the country. The Klan spread from the South into the Midwest and Northern states, and into Canada where there was a large movement against Catholic immigrants. At its peak, Klan membership exceeded four million and comprised 20% of the adult white male population in many broad geographic regions, with 40% in some areas. Most of the membership resided in Midwestern states.

The KKK controlled Southern legislatures and the governments of Tennessee, Indiana, Oklahoma, and Oregon. In Indiana, Republican Klansman Edward Jackson was elected governor in 1924.

In another well-known example from the same year, the Klan decided to make Anaheim, California, into a model Klan city. It secretly took over the City Council, but the city conducted a special recall election and Klan members were voted out.

Klan delegates played a significant role at the path-setting 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City, often called the “Klanbake Convention.” The convention initially pitted Klan-backed candidate William Gibbs McAdoo against Catholic New York Governor Al Smith. After days of stalemates and rioting, both candidates withdrew in favor of a compromise. Klan delegates defeated a Democratic Party platform plank that would have condemned their organization. On July 4, 1924, thousands of Klansmen celebrated victory on a nearby field in New Jersey by burning effigies of Smith and by burning crosses.

In some states, such as Alabama, the KKK worked for political and social reform. The state’s Klansmen were among the foremost advocates of better public schools, effective prohibition enforcement, expanded road construction, and other “progressive” political measures. In many ways these reforms benefited lower class white people. By 1925, the Klan was a political force in the state, as leaders like J. Thomas Heflin, David Bibb Graves, and Hugo Black manipulated the KKK membership against the power of Black Belt planters who had long dominated the state.

Black was elected senator in 1926 and later became a Supreme Court Justice. In 1926, with Klan support, a former Klan chapter head named Bibb Graves won the Alabama governor’s office. He pushed for increased education funding, better public health, new highway construction, and pro-labor legislation. Because the Alabama state legislature refused to redistrict until 1972, however, even the Klan was unable to break the planters’ and rural areas’ hold on power.

Many groups and leaders, including prominent Protestant ministers such as Reinhold Niebuhr in Detroit, spoke up against the Klan. To blunt attacks against Jewish Americans and conduct public education, the Jewish Anti-Defamation League was formed after the lynching of Leo Frank. When one civic group began to publish Klan membership lists, the number of members quickly declined. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People carried on public education about Klan activities and lobbied against Klan abuses in Congress. After its peak in 1925, Klan membership began to decline rapidly in most areas of the Midwest.

In Alabama, KKK vigilantes, thinking they had governmental protection, launched a wave of physical terror in 1927, targeting both blacks and whites for violating racial norms and perceived moral lapses. The state’s conservative elite counterattacked. Grover C. Hall, Sr., editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, began a series of editorials and articles attacking the Klan for their “racial and religious intolerance.” Hall won a Pulitzer Prize for his crusade. Other newspapers kept up a steady, loud attack on the Klan as violent and “un-American.” Sheriffs cracked down. In the 1928 presidential election, the state voted for the Democratic candidate Al Smith, although he was Catholic. Klan membership in Alabama dropped to less than six thousand by 1930. Small independent units continued to be active in Birmingham, where in the late 1940s, members started a program of bombings against the homes of upwardly mobile African Americans. KKK activism increased against the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

When the Grand Dragon of Indiana and fourteen states, David Stephenson, was convicted of the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer, the Klan declined further. Stephenson was convicted in a sensational trial. According to historian Leonard Moore, a leadership failure caused the organization’s collapse:

Stephenson and the other salesmen and office seekers who maneuvered for control of Indiana’s Invisible Empire lacked both the ability and the desire to use the political system to carry out the Klan’s stated goals. They were disinterested in, or perhaps even unaware of, grass roots concerns within the movement. For them, the Klan had been nothing more than a means for gaining wealth and power. These marginal men had risen to the top of the hooded order because, until it became a political force, the Klan had never required strong, dedicated leadership. More established and experienced politicians who endorsed the Klan, or who pursued some of the interests of their Klan constituents, also accomplished little. Factionalism created one barrier, but many politicians had supported the Klan simply out of expedience. When charges of crime and corruption began to taint the movement, those concerned about their political futures had even less reason to work on the Klan’s behalf.

Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley Evans sold the organization in 1939 to James Colescott, an Indiana veterinarian, and Samuel Green, an Atlanta obstetrician, but they were unable to staunch the exodus of members. The Klan’s image was further damaged by Colescott’s association with Nazi-sympathizer organizations, the Klan’s involvement in the 1943 Detroit Race Riot, and efforts to disrupt the American war effort during World War II. In 1944, the IRS filed a lien for $685,000 in back taxes against the Klan, and Colescott was forced to dissolve the organization in 1944.

After WWII, folklorist and author Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the Klan and provided information to media and law enforcement agencies. He also provided secret code words to the writers of the Superman radio program, resulting in episodes in which Superman took on the KKK. Kennedy’s intention to strip away the Klan’s mystique and trivialize the Klan’s rituals and code words may have contributed to the decline in Klan recruiting and membership. In the 1950s, Kennedy wrote a bestselling book about his experiences, which further damaged the Klan.

Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer & Sources

BIRTH OF A NOTION WALLPAPER is now available for your computer. Click here.