Crossposted from Left Toon Lane, Bilerico Project & My Left Wing

click to enlarge

From Wikipedia:

Prior to the Tuskegee Airmen, no U.S. military pilots had been black. A series of legislative moves by the United States Congress in 1941 forced the Army Air Corps to form an all-black combat unit, despite the War Department’s reluctance. In an effort to eliminate the unit before it could begin, the War Department set up a system to accept only those with a level of flight experience or higher education that they expected would be hard to fill. This policy backfired when the Air Corps received an abundance of applications from men who qualified even under these restrictive specifications, many of whom had already participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which the Tuskegee Institute had participated in since 1939.

The U.S. Army Air Corps had established the Psychological Research Unit 1 at Maxwell Army Air Field, Alabama, and other units around the country for aviation cadet training, which included the identification, selection, education, and training of pilots, navigators and bombardiers. Psychologists employed in these research studies and training programs used some of the first standardized tests to quantify IQ, dexterity, and leadership qualities in order to select and train the right personnel for the right role (bombardier, pilot, navigator). The Air Corps determined that the same existing programs would be used for all units, including all-black units. At Tuskegee, this effort would continue with the selection and training of the Tuskegee Airmen.

On 19 March 1941, the 99th Pursuit Squadron (Pursuit being the pre-World War II descriptive for “Fighter”) was activated at Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois. Over 250 enlisted men were trained at Chanute in aircraft ground support trades. This small number of enlisted men was to become the core of other black squadrons forming at Tuskegee and Maxwell Fields in Alabama.

In June 1941, the Tuskegee program officially began with formation of the 99th Fighter Squadron at the Tuskegee Institute, a highly regarded university founded by Booker T. Washington, through the work of Lewis Adams and George W. Campbell (Tuskegee, Alabama) in Tuskegee, Alabama. The unit consisted of an entire service arm, including ground crew. After basic training at Moton Field, they were moved to the nearby Tuskegee Army Air Field about 16 km (10 miles) to the west for conversion training onto operational types. The Airmen were placed under the command of Capt. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., one of the few African American West Point graduates. His father Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. was the first black general in the U.S. Army.

During its training, the 99th Fighter Squadron was commanded by white and Puerto Rican officers, beginning with Maj. James Ellison. By 1942, however, it was Col. Frederick Kimble who oversaw operations at the Tuskegee airfield. Kimble maintained segregation on the field in deference to local customs – a policy the airmen resented. Later that year, the Air Corps replaced Kimble with the director of Instruction at Tuskegee Army Airfield, Maj. Noel F. Parrish. Parrish, counter to the prevalent racism of the day, was fair and open-minded, and petitioned Washington to allow the Tuskegee Airmen to serve in combat.

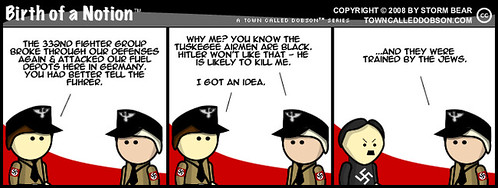

The 99th was ready for combat duty during some of the Allies’ earliest actions in the North African campaign, and was transported to Casablanca, Morocco, on the USS Mariposa. From there, they travelled by train to Oujda near Fes, and made their way to Tunis to operate against the Luftwaffe. The flyers and ground crew were largely isolated by racial segregation practices of their initial command, the 33rd Fighter Group and its commander Col. William W. Momyer, and left with little guidance from battle-experienced pilots beyond a week spent with Col. Phillip Cochran. The 99th’s first combat mission was to attack the small but strategic volcanic island of Pantelleria in the Mediterranean Sea between Sicily and Tunisia, in preparation for the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The 99th moved to Sicily where it received a Distinguished Unit Citation for its performance in combat.

However, Col. Momyer told media sources in the U.S. that the 99th was a failure and its pilots cowardly, incompentent or worse, resulting in a critical article in Time magazine. In response, a hearing was convened before the House Armed Services Committee to determine whether the Tuskegee Airmen “experiment” should be allowed to continue. Momyer accused the Airmen of being incompetent—based on the fact that they had seen little air-to-air combat during their time in theatre. To bolster the recommendation to scrap the project, a member of the committee commissioned and then submitted into evidence a “scientific” report by the University of Texas which purported to prove that Negroes were of low intelligence and incapable of handling complex situations (such as air combat). Col. Davis forcefully refuted the committee members’ claims, but only the intervention of Col. Emmitt “Rosie” O’Donnell prevented a recommendation for disbandment of the squadron from being sent to president Franklin D. Roosevelt. General Hap Arnold decided an evaluation of all Mediterranean Theatre P-40 units would be undertaken to determine the true merits of the 99th. The results showed the 99th FS to be as good or better than the other American units operating the fighter.

Shortly after the hearing, three new squadrons fresh out of training at Tuskegee embarked for Africa. After several months operating separately, all four squadrons were combined to form the all-black 332nd Fighter Group.

The Tuskegee Airmen were initially equipped with P-40 Warhawks, briefly with P-39 Airacobras (March 1944), later with P-47 Thunderbolts (June-July 1944), and finally with the airplane that they would become most identified with, the P-51 Mustang (July 1944).

On 27 January and 28 January 1944, Luftwaffe Fw 190 fighter-bombers raided Anzio, where the Allies had conducted amphibious landings on January 22. Attached to the 79th Fighter Group, eleven of the 99th Fighter Squadron’s pilots shot down enemy fighters, including Capt. Charles B. Hall, who claimed two shot down, bringing his aerial victory total to three. The eight fighter squadrons defending Anzio together claimed 32 German aircraft shot down whilst the 99th claimed the highest score among them with 13.

The squadron won its second Distinguished Unit Citation on 12 May-14 May 1944, while attached to the 324th Fighter Group, attacking German positions on Monastery Hill (Monte Cassino), attacking infantry massing on the hill for a counterattack, and bombing a nearby strong point to force the surrender of the German garrison to Moroccan Goumiers.

By this point, more graduates were ready for combat, and the all-black 332nd Fighter Group had been sent overseas with three fighter squadrons: the 100th, 301st and 302nd. Under the command of Col. Benjamin O. Davis, the squadrons were moved to mainland Italy, where the 99th FS, assigned to the group on 1 May, joining them on 6 June. The Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group escorted bombing raids into Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Germany. Flying escort for heavy bombers, the 332nd racked up an impressive combat record. Reportedly, the Luftwaffe awarded the Airmen the nickname, “Schwarze Vogelmenschen,” or “Black Birdmen.” The Allies called the Airmen “Redtails” or “Redtail Angels,” because of the distinctive crimson paint on the vertical stabilizers of the unit’s aircraft. Although bomber groups would request Redtail escort when possible, few bomber crew members knew at the time that the Redtails were black.

A B-25 bomb group, the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium), was forming in the U.S. but completed its training too late to see action. The 99th Fighter Squadron after its return to the United States became part of the 477th, redesignated the 477th Composite Group.

By the end of the war, the Tuskegee Airmen were credited with 109 Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, the German-operated Italian destroyer TA-23 sunk by machine-gun fire, and destruction of numerous fuel dumps, trucks and trains. The squadrons of the 332nd FG flew more than 15,000 sorties on 1,500 missions. The unit received recognition through official channels and was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation for a mission flown March 24, 1945, escorting B-17s to bomb the Daimler-Benz tank factory at Berlin, Germany, an action in which its pilots were credited with destroying three Me-262 jets, all belonging to the Luftwaffe’s all-jet Jagdgeschwader 7, in aerial combat that day, despite the American unit initially claiming 11 Me 262s on that particular mission. However on examing German records, JG 7 records just four Me 262s were lost and all of the pilots survived. In return the 463rd Bomb Group, one of the many B-17 groups the 322nd were escorting, lost two bombers. The 322nd themselves lost three P-51s during the mission. The bombers also made substantial claims, making it impossible to tell which units were responsible for those individual four kills. The 99th Fighter Squadron in addition received two DUCs, the second after its assignment to the 332nd FG. The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded several Silver Stars, 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 8 Purple Hearts, 14 Bronze Stars and 744 Air Medals. In all, 992 pilots were trained in Tuskegee from 1940 to 1946; about 445 deployed overseas, and 150 Airmen lost their lives in accidents or combat.

While it had long been said that the Redtails were the only fighter group who never lost a bomber to enemy fighters, suggestions to the contrary, combined with Air Force records and eyewitness accounts indicating that at least 25 bombers were lost to enemy fire, resulted in the Air Force conducting a reassessment of the history of this famed unit in late 2006. The claim that no bomber escorted by the Tuskegee Airmen had ever been lost to enemy fire first appeared on 24 March 1945, in the Chicago Defender, under the headline “332nd Flies Its 200th Mission Without Loss.” According to the 28 March 2007 Air Force report, however, some bombers under 332nd Fighter Group escort protection were shot down on the very day the Chicago Defender article was published. The subsequent report, based on after-mission reports filed by both the bomber units and Tuskegee fighter groups as well as missing air crew records and witness testimony, was released in March 2007 and documented 25 bombers shot down by enemy fighter aircraft while being escorted by the Tuskegee Airmen.

The controversy continued to attract news media attention in 2008. A St. Petersburg Times article quoted a historian at the Air Force Historical Research Agency as confirming the loss of up to 25 bombers. Disputing this, a professor at the National Defense University in Washington said he researched more than 200 Tuskegee Airmen mission reports and found no bombers were lost to enemy fighters. Bill Holloman, a Tuskegee airman who taught black studies at the University of Washington and now chairs the Airmen’s history committee, was reported by the Times as saying his review of records did confirm lost bombers, but “the Tuskegee story is about pilots who rose above adversity and discrimination and opened a door once closed to black America — not about whether their record is perfect”. One mission report states that on 26 July 1944: “1 B-24 seen spiraling out of formation in T/A (target area) after attack by E/A (enemy aircraft). No chutes seen to open.” A second report, dated 31 August 1944, praises group commander Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. by saying he “so skillfully disposed his squadrons that in spite of the large number of enemy fighters, the bomber formation suffered only a few losses.”

Far from failing as originally expected, a combination of pre-war experience and the personal drive of those accepted for training had resulted in some of the best pilots in the U.S. Army Air Corps. Nevertheless, the Tuskegee Airmen continued to have to fight racism. Their combat record did much to quiet those directly involved with the group (notably bomber crews who often requested them for escort), but other units were less than interested and continued to harass the Airmen.

All of these events appear to have simply stiffened the Airmen’s resolve to fight for their own rights in the US. After the war, the Tuskegee Airmen once again found themselves isolated. In 1949, the 332nd entered the annual All Air Force Gunnery Meet in Las Vegas, Nevada and won. After segregation in the military was ended in 1948 by President Harry S. Truman with Executive Order 9981, the Tuskegee Airmen now found themselves in high demand throughout the newly formed United States Air Force. Some taught in civilian flight schools, such as the black-owned Columbia Air Center in Maryland.

Many of the surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen annually participate in the Tuskegee Airmen Convention, which is hosted by Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.

In 2005, four Tuskegee Airmen (Lt. Col. Lee Archer, Lt. Col. Robert Ashby, MSgt. James Sheppard, and TechSgt. George Watson) flew to Balad, Iraq, to speak to active duty airmen serving in the current incarnation of the 332nd, reactivated as first the 332nd Air Expeditionary Group in 1998 and made part of the 332nd Air Expeditionary Wing. “This group represents the linkage between the ‘greatest generation’ of airmen and the ‘latest generation’ of airmen,” said Lt. Gen. Walter E. Buchanan III, commander of the Ninth Air Force and US Central Command Air Forces, in an e-mail to the Associated Press.

Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer & Sources

BIRTH OF A NOTION WALLPAPER is now available for your computer. Click here.