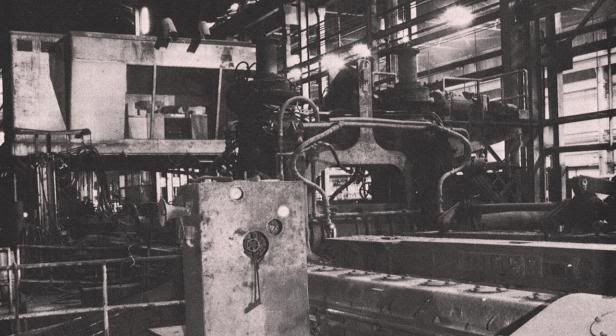

Chilly drafts of wind pour through cracked windows and holes in the roof of Bethlehem Steel’s tool shop. The interior looks like life had suddenly stopped, as though men had simply abandoned work stations and left their equipment to rot. Pigeon dirt covers rolling tables where streams of steel billets used to flow. In nearby sheds, hundreds of dies, once meticulously cut by skilled craftsmen, sit rusting and neglected because someone else’s dies are now shaping this nation’s tool steel.

– – John Strohmeyer, 1985

Abandoned oil refining plant, near Philadelphia, 2007

America began de-industrializing 35-40 years ago, but the process continues. It is a problem that free market capitalism cannot solve, because it is natural for capital to avoid long-term investment, in particular avoiding high-wage nations. It will be hard on us here in the U.S. if our Ivy League masters fail to understand what America’s basic economic problem is, or are too sold out to do anything about it even if they do understand. Only government can do anything here, and foregoing short-term profit for long-term benefit would involve short-term pain for the capitalist class. One person who does understand the underlying problem is Michael Perelman, who writes (emphasis added):

With all the attention to the current financial crisis, the time has come to look at another part of market failure — the reluctance to invest in long-lived plant and equipment. I’m not merely thinking about the deindustrialization of the US economy, but a more general reluctance. . . .

The most popular response to this reluctance to invest [was the Joseph Schumpeter concept,] creative destruction.

The idea was that when the economy became sluggish, new innovations would be so profitable that investors would rush in and build up whole new industries. In doing so, they would destroy existing industry, but the net effect was to enliven the entire economy. For Schumpeter, this creative destruction was the lifeblood of capitalism.

Schumpeter liked to use transportation as a dramatic example of creative destruction. [In the early 19th Century, c]anals slashed the cost of transportation, while setting off an economic boom. Railroads followed with another revolution in transportation, setting off another boom. Finally, the internal combustion engine allowed trucks to haul freight with even more savings, creating still another boom.

But wait! Where are the entrepreneurs? Government, not entrepreneurs, provided the wherewithal for these transportation revolutions. Governments built the canals. Governments financed the railroads with land grants and other subsidies. Governments built the highways that made possible freight hauling by trucks. Schumpeter could not have chosen a more perfect example [of how uninvolved entrepreneurs were in the long-term investment that created new transportation infrastructures]..

Entrepreneurs have good reason not to make such investments. Industries that depend on capital-intensive plant and equipment have difficulty withstanding strong competition, which forces prices down near the cost of production. But, as any introductory economics text explains, previous investments are not part of the cost of production. Unless prices are far in excess of the cost of production, a business with long-lived capital will be unable to recoup the cost of its investment. . .

Indeed, during the 19th century, railroads went bankrupt with some regularity, much as the airlines do today. [Nonetheless, such long-term] investment creates jobs that create the demand that keep the rest of the economy going. Spurts of sound investment occur after wars or depressions wipe out large swaths of capital. The period following World War II, known as the Golden Age, was a perfect example. Business can hope to pull in huge profits before the market becomes saturated.

The dot.com boom seemed to be a counter example, but in fact the physical investment for much of that period relatively small. Once the boom was underway, then irrational euphoria brought unprofitable investment online, which ultimately could not be supported.

This reluctance to invest extends to replacement of capital goods. The steel industry near where I grew up was working with factories that were built before World War I. The Great Depression forced more competitive industries to modernize, but, once the crisis passed, they too let their productive capacity age. No wonder deindustrialization swept across the United States, beginning in the 1970s. . . .

In short, the evidence that markets are sufficient to generate investment is lacking – [except when] the business cycle reaches the stage of euphoria. At that point, much of the investment will be irrational.

As business stagnates and profits fall, money will seek higher profits and finance, which will become riskier and riskier. Eventually, the house of cards falls, irrational and outdated investment becomes scrapped, and one of two things will happen. After a painful depression, bankruptcies will wipe out a good deal of debt. New investment opportunities present themselves. Eventually, the economy will be reinvigorated for a while until the cycle begins again. Alternatively, the dislocation of the depression to a different way of organizing production.

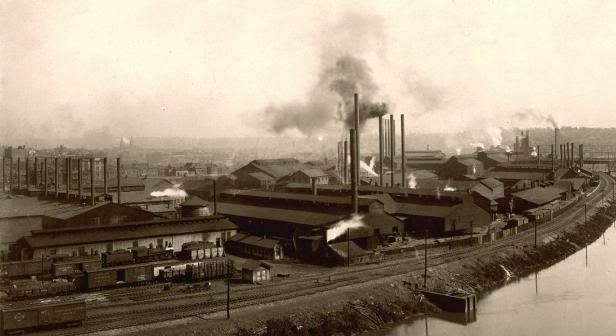

Our social challenge is to return to a non-financial industrial economy that is in harmony with the earth. So, like the picture below but without poisoning the air, water and ground. And away from the internal combustion engine.

Steel plant, Youngstown, Ohio, 1905

I don’t expect President Obama will embark on this social democratic path, which embraces planning and industrial and wage policy, and abandons the ‘market’ forces he has been officially and rhetorically in love with. But I’ll sit and hope, for a short while.

China and the Asian tigers must be incredibly stupid to build plants instead of creating CDO’s.

I think something is wrong with modern capitalism’s concepts.

And we were incredibly stupid to open up our markets to them while they closed theirs to us. But then, we did that so multinational companies could get cheap labor to sell cheap stuff to us a Walmart.

Agreed. All the way.