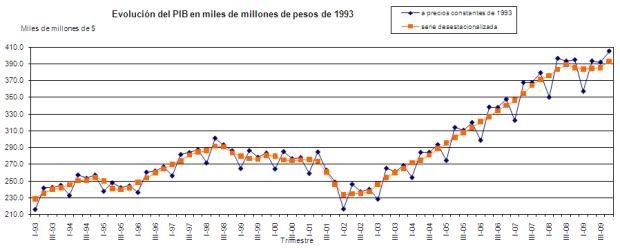

Argentina GDP growth since 1993, in 1993 pesos

Defying BBC and others’ severe pessimism, Argentina’s economy performed well from 2002 forward, after it decided to default on its debt in late 2001. So, Greece, why not just skip to the Argentina story from the default forward? Why go through your own version of the hell of Argentina’s 1999 to 2001, IMF-imposed austerity? Dean Baker:

Argentina’s economy shrank in the first quarter of 2002, the quarter immediately following the December default, and then began growing robustly. It continued to have robust growth for 5 more years until it got caught up in the world recession. If we were having an honest debate over Greece, then everyone would be talking about Argentina’s remarkable turnaround.

Now the fact seems to be that Greece has bought itself at most a year before its debt is restructured anyway. The Financial Times:

However, most of the lawyers, bankers, and emerging market investors who have worked on the dozens of sovereign defaults over the past three decades have not changed their view on the fundamentals of the distressed European sovereigns. Among them, the betting is that Europe and the International Monetary Fund have bought no more than another six months to a year before a “restructuring”.

So, why not skip the year of irrational and severe austerity? Joe Stiglitz:

What worries me about the rescue package that has been put together is that it is accompanied by severe austerity measures that are likely to lead to a weaker European economy. A weaker European economy is going to increase the deficit so that in fact the deficit reduction that people hope for will not fully be realized. There may be some, but it will be limited.

The risk is that Europe goes into the kind of death spiral that Argentina went in when it had a fixed exchange rate with the United States. It did not want to abandon that fixed exchange rate, there was no assistance of a substantial kind coming. Eventually concretionary measures were imposed and the deficit reduction was not what they had hoped. Finally it abandoned the currency, the fixed exchange rate, and it defaulted on the debt.”

I.e., why not skip today to Euro-escape devaluation (hopefully!) and default and then to that real nice growth stage?

The word is, restructuring on terms very favorable to Greece is doable. The Financial Times again:

It would seem that, were Greece to reschedule the maturities of its state debt, or reduce the real value of the debt, it would be in a much better position to do so, from a legal and logistical point of view, than other states have been in recent decades.

And how to do ‘it’ has all been worked out well, by fine authorities, in How to Restructure Greek Debt.

Excellent background on what an instructive example the Argentina should be is in Argentina: Greek financial rescue doomed to fail:

Argentina also had to go it alone after failing to make the deep cuts demanded by the International Monetary Fund to secure more loans. The country in 2001 was in many ways where Greece and other southern European nations are today, with its economy sputtering, companies failing and huge debts coming due. But instead of a trillion-dollar rescue to keep Greece from defaulting, Argentina got a cold shoulder from lenders.

While Europe’s rescue package announced this week has at least postponed the worst — a domino effect of defaults across Europe that could drag down the euro and even break up the European Union — Argentina ran out of options. It defaulted and had to figure out how to rebuild its economy without outside help.

But in its isolation, the country boomed. By boosting government spending to stimulate the economy, Argentina increased its GDP by more than 50 percent since 2003, and now plans to emerge from default by resolving the last of its bad debts.

President Cristina Fernandez says Argentina’s experience shows that austerity measures are exactly the wrong medicine in a debt crisis, which is why Europe’s rescue plan is “condemned to failure.”

“You don’t need to be an economist to know that if you reduce the flow of economic activity, you reduce even more the capacity to pay the debt,” Fernandez said in a national address this week. “It’s clear that you won’t be able to pay what you’re being lent.”

Even supporters of Europe’s rescue package say Greece, Portugal, Spain and other overly indebted European countries now face years of wage cuts, increased taxes and living with less to have a chance of avoiding national bankruptcy.

But getting your financial house in order is the best prescription for growth, European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet said in an interview published Friday on the bank’s website, expressing an orthodox economic theory that is directly opposed to Argentina’s position.

“It is a complete fallacy to say that fiscal soundness dampens growth. It is exactly the contrary,” Trichet said. “It is the absence of fiscal credibility which dampens growth.”

Let’s hope Trichet is the outlier (yeah, right!), and economic rationality will prevail. After all, says the real Argentina story, they tried it the Trichet way and it just got them more and worsening misery:

Before its default, Argentina had spent years following Washington’s economic doctrine — privatizing public services, dropping trade barriers, taking out huge loans and linking the peso 1-to-1 to the dollar. Then its economy slowed in the late 1990s, and it found it had borrowed more than it could pay back.

The IMF, which liberally lent Argentina money in good times, said draconian cuts in government salaries and pensions had to be made before fresh loans could be offered — at 6 percent interest, a rate Argentines thought was obscenely high.

It fell to Argentina’s economy minister Ricardo Lopez Murphy to announce the austerity measures in the spring of 2001: $2 billion in budget cuts, including a sharp drop in education spending. Massive street protests forced his resignation in days. But the economy kept souring, and debt payments loomed. With no political consensus for unpopular measures, Argentina drove its economy off a cliff — declaring its world-record default and devaluing its currency.

Further corrective to Trichet’s perspective is in an enlightening discussion at Al Jazeera, The impact of Greece’s downturn, particularly Mark Weisbrot from 5’30”. In short, “You can’t shrink your way out of a recession.” Duh-oy-e-e.