A relatively new natural gas drilling technique – hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking” – is being rushed into wide scale use with the same heedless abandon as deep water oil drilling. Activists are trying to put the brakes on it before fracking has the chance to produce its own version of last year’s BP oil spill.

Cross posted from Pruning Shears.

No Associated Press content was harmed in the writing of this post

BACKGROUND

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Marcellus Shale is “a sedimentary rock formation deposited over 350 million years ago in a shallow inland sea located in the eastern United States where the present-day Appalachian Mountains now stand” and it “contains significant quantities of natural gas.” How significant? Well, it kind of depends on whom you ask. University researchers said there was quite a bit, but a key industry player claimed a wildly larger amount (emph. added):

In 2008, two professors at Pennsylvania State University and the State University of New York (SUNY) Fredonia estimated that about 50 TCF (trillion cubic feet) of recoverable natural gas could be extracted from the Marcellus Shale (Engelder and Lash, 2008). In November 2008, on the basis of production information from Chesapeake Energy Corporation [remember that name! – ed.], the estimate of recoverable gas from the Marcellus Shale was raised to more than 363 TCF (Esch, 2008).

Asking Chesapeake Energy if it was worthwhile to drill in an area where they had a direct financial interest seems a bit like asking Tobacco Institute scientists if smoking is linked to lung cancer, no? An increase of over 700% ought to be looked into, not blandly passed along. But either way, there’s a lot of natural gas under them thar hills and it is, as the USGS helpfully notes in its summary, “an abundant, domestic energy resource that burns cleanly, and emits the lowest amount of carbon dioxide per calorie of any fossil fuel.”

Chesapeake is on the same page, touting natural gas as “clean, affordable, abundant” and flatly states: “The only scalable, affordable alternative to burning dirty coal is to burn clean natural gas.” This is an extremely relevant and compelling point if the natural gas packages itself, grows legs and walks to the surface. Sadly, it remains stubbornly immobile. So the alternative is to force it out via directional drilling,

which involves steering a downhole drill bit in a direction other than vertical. An initially vertical drillhole is slowly turned 90 degrees to penetrate long horizontal distances, sometimes over a mile, through the Marcellus Shale bedrock. Hydraulic fractures are then created into the rock at intervals from the horizontal section of the borehole, allowing a substantial number of high-permeability pathways to contact a large volume of rock (fig. 5).

This drilling process requires a large quantity of water to hydraulically fracture the rock (hence the nickname “fracking”), and that water turns into a toxic stew:

Along with the introduced chemicals, hydrofrac water is in close contact with the rock during the course of the stimulation treatment, and when recovered may contain a variety of formation materials, including brines, heavy metals, radionuclides, and organics that can make wastewater treatment difficult and expensive. The formation brines often contain relatively high concentrations of sodium, chloride, bromide, and other inorganic constituents, such as arsenic, barium, other heavy metals, and radionuclides that significantly exceed drinking water standards (Harper, 2008).

No matter how clean it is when you actually consume it, the process of getting to it is unbelievably dirty. Even the USGS acknowledges as much: “While the technology of drilling directional boreholes, and the use of sophisticated hydraulic fracturing processes to extract gas resources from tight rock have improved over the past few decades, the knowledge of how this extraction might affect water resources has not kept pace.”

Drilling technology sprinting past environmental protection – sound familiar?

EARLY RESULTS

That’s all very theoretical and academic, but how are these early adventures into fracking going? Not so well. In some cases it is merely disturbing, as in this video of a compressor station emitting lots of noise and…stuff. Since we still do not have any sensible regulation of this process – hell, since we aren’t even aware what the byproducts and long term consequences are – it’s kind of hard to see footage like that and not be suspicious of what exactly is going on. Literally no one knows.

The independent, non-profit news organization ProPublica has an entire series devoted to the threat posed by fracking, and has uncovered several examples of the damage done by it. An award-winning documentary called GasLand has shown in frightening detail just how hazardous it is. And these problems are just when it all goes according to plan. When things go wrong, as it did with one of Chesapeake’s operations in Pennsylvania last week, (via) it’s even worse (via).

This is not just happening in America, either. The industry is trying to get a foothold in Europe, but its reputation has already preceded it. Hilariously, UK gas company CEO Mark Miller trots out the bad apples argument to try and wave off the poor track record. (Ever since Abu Ghraib “bad apples” has been the go-to talking point for high ranking officials looking to evade responsibility. Even putting aside the cheap and obvious scapegoating involved, the phrase itself is a clip from a proverb that, if fully considered, isn’t exactly exonerating.)

While major players are fiercely opposed to even simple disclosure, there is enough concern about the practice for some knowledgeable parties to sound the alarm – and thankfully not every politician is in the thrall of industry lobbyists. Still, ProPublica considers the industry at a turning point (via): one where we will either start seeing effective regulation or the same “consequences be damned” heedlessness we’ve seen elsewhere. I happen to be deeply skeptical of regulation, and I’ve gone on and on about it previously. The short version is that between cognitive regulatory capture and the starving of agencies of proper resources, the whole idea of regulation has not worked well in practice.

CLOSE TO HOME

Opposition to fracking has been growing (via), and Ohio is no exception. Our idiot governor has decided it’s a swell idea to approach economically desperate people with drilling proposals in exchange for a one-time shot of money. Chesapeake is aggressively buying up rights and has lined up a willing local front group to, I don’t know, put cartoon buckeye stickers on the equipment.

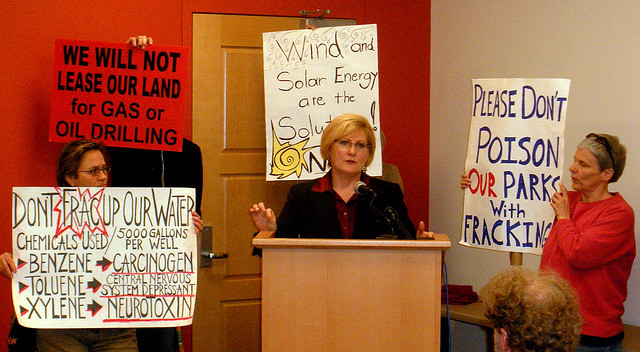

The state legislature is considering a proposal to open additional state lands to drilling, and in response local activists staged a protest on Tuesday (via ProgressOhio‘s Flickr page):

State Rep. Teresa Fedor spoke at the rally:

And she noted – with commendable understatement – “There’s a lot that we don’t know about this new and unconventional drilling.” (Read about previous Fedor awesomeness here.)

Her point shouldn’t really be controversial at all. Considering the problems, and in some cases catastrophes, that we already know about elsewhere it shouldn’t be terribly provocative to cool it for a bit and try to get a better grip on what’s happening. Unfortunately there are people like Tom Stewart of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association offering rebuttals such as this, which I wish I were making up:

With energy development or with any kind of economic activity, there’s always going to be an environmental footprint. Airplanes do fall out of the sky. … What Ohio citizens need to be concerned about is that the proper regulatory process is in place to regulate the industry, to ensure the public that they can have faith and trust that this is done properly.

The GOP-dominated legislature seems likely to do Chesapeake’s bidding and open up more public land for this private company to profit from. But the opposition has been getting the word out, and doing so with increasing visibility. The issue won’t go away until Chesapeake and their ilk go away (and until their sponsors in Columbus do as well), but in this case – as with the phenomenally energetic referendum effort to repeal SB 5 – citizen action might yet veto corporate greed.

<hr>

Notes

- There’s a nice Marcellus Shale map for Ohio here.

- From the USGS paper:

The United States uses about 23 TCF of natural gas per year (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2009), so the Marcellus gas resource may be large enough to supply the needs of the entire Nation for roughly 15 years at the current rates of consumption.

From the Chesapeake site:

now estimated to contain more than two quadrillion cubic feet of natural gas, more than doubling America’s previously estimated natural gas reserves, and giving us close to a 200-year supply of clean, affordable, American natural gas.

Not sure where the extra 185 years supply comes from. But then notice this from the Guardian piece:

Within two years, predicts James Smith, outgoing UK chairman of Shell, the company will go from being an oil business to a gas producer. “Estimates show that we could have enough gas to power the world for 200 years,” he said.

So maybe 200 years is the Friedman Unit of fracking.

- From the Chesapeake site:

Wind and solar facilities are not economic without taxpayer or ratepayer subsidies.

From the USGS paper:

From the mid-1970s to early 1980s, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) funded the Eastern Gas Shales Project (EGSP) to develop new technology in partnership with industry that would advance the commercial development of Devonian shale gas (Schrider and Wise, 1980).

Why is it that government funding is a partnership when given to fossil fuel companies but a subsidy when given to renewable energy companies?

- Last week I listened to the radio for the first time in a long, long while – probably over a year (see my “Free MP3 sites” blogroll!) I was tuned to a “morning zoo in the afternoon” type show for less than an hour. In that tiny, rare sampling of time I heard a Chesapeake commercial. A cheerful voice explained that no one cares more about the environment than Chesapeake, so if you own mineral rights why not give us a call? The fracking industry has been incredibly aggressive on this initiative.

- A minor complaint, but I don’t like seeing the word “brine” used to describe any part of the fracking wastewater. It makes it sound like something you might encounter when tromping around the Scottish highlands instead of the poisonous brew created by blowing a bunch of shit to smithereens deep underground and then hauling it to the surface.

Danps — I’m sure you’ve seen the recent Cornell study on fracking, regarding potential contributions to overall climate change. Basically, industry claims that natural gas is a clean alternative to coal & oil are seriously questioned.

How about the recent expose’ by that leftist rag, the New York Times, regarding previously suppressed information on fracking hazards?

link

My community sits on some of the most ‘promising’ areas of play in the Marcellus Shale; I’ve been shouting about this for years now, to anyone who’ll listen. The energy companies have been six steps ahead of us until very recently, putting the full measure of deceit & persuasion against the interests of communities throughout the state, preying on the poor, uninformed & self-interested. In the last election, millions of dollars were poured into a GOP challenge to our progressive congressman, Maurice Hinchey, who introduced the Frac Act in Congress & is a staunch opponent of business as usual. He retained his seat.

Now Chesapeake, once the predominant interest in exploiting New York’s gas plays, is busily selling off leases to other companies & moving elsewhere, due to oppositional hang-ups in New York. One of those ‘elsewheres’ has clearly been Ohio.

It’s absolutely crucial that we all get ourselves up to speed & active against these interests as quickly as possible! There are no positive aspects to what they’re doing aside of potential profit & there is no morality involved. Their exploitation of our resources isn’t even likely to address domestic energy consumption, because the market is global.

BTW, we do not currently have a natural gas shortage, so the hellish rush & obscene pressure to develop is only, again, a matter of potential profit.

Thanks much, wilderness wench.

Re: not having a shortage, one of the talking points by the industry is that we have to do this stuff because consumers are just using too darn much energy. I tend to think that’s a guilt trip (like the argument that food prices have spiked because we’re using commodities like corn in alternative fuels). At the very least, rising demand can be met with conservation measures and alternative sources – particularly solar.

Well, in order for crisis capitalism to work, there’s gotta be a crisis. If there’s no crisis, it has to be manufactured, either in actuality or in perception. Naturally the crisis must be manipulated to benefit the interested parties .. or else the crisis doesn’t exist. Even if it does (see climate change).