Let me get this out of the way from the start. I am not an economist. I was a lawyer before my disability, though. My first specialty was in bankruptcy, so I am all too familiar with what happens when a corporation or business becomes insolvent. In many cases firms went bankrupt because they failed to invest in new technologies, especially technologies regarding safety, both safety for the general public who purchased their products and safety for their workers. They went for short term profits, and denied the risks they were taking, risks they knew about that were ignored.

This is the problem we are experiencing right now with our world and the global effects of climate change. No one in our government seemingly has the political will to tell the truth that our time is running out merely to limit the damage global warming has wrought, much less prevent it. No one is willing to stick their necks out and demand we invest in our resources into eliminating carbon emissions by any means necessary.

Like any number of firms I dealt with after they went belly up, our political policy makers are in active denial of the risks they are taking by not addressing climate change. For any number of reasons, including a very well funded effort to disseminate lies and disinformation to the public by those who profit from ignoring the effects of our ever increasing release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, our political leaders here and elsewhere are reluctant to address the elephant in the room that even Tom Friedman (yes that Tom Friedman) has admitted exists:

You really do have to wonder whether a few years from now we’ll look back at the first decade of the 21st century — when food prices spiked, energy prices soared, world population surged, tornados plowed through cities, floods and droughts set records, populations were displaced and governments were threatened by the confluence of it all — and ask ourselves: What were we thinking? How did we not panic when the evidence was so obvious that we’d crossed some growth/climate/natural resource/population redlines all at once?

Tom, I’ll tell you why, at least in part. It’s because too many of our policy makers are relying ion traditional, conservative economic advisers when it comes to assessing the risks of climate change versus the cost of eliminating those pesky carbon emissions that are primarily responsible for global warming.

Conservative economists by the bucket load will rant and rail for hours at a time about why the cost of reducing and eventually eliminating CO2 emissions is too expensive. What they always fail to consider (or gloss over) is the risks and uncertainties of doing nothing. In general they underestimate the risks and overestimate the ability of human beings to adapt. For example:

(cont)

For the present discussion, the salient fact is that virtually all the economic models used for this purpose share something in common: they show human beings getting richer over the next century, regardless of what the climate does. […]

[Eban Goodstein is the director of the Bard Center for Environmental Policy]:

My E3 colleague Frank Ackerman has noted that even assuming what [British economist Nicholas] Stern characterizes as an extreme worst case scenario — a 35 percent reduction in income below baseline — then the world would “only” be eight times richer in 2200. Similarly, the IPCC’s four “marker scenarios” all forecast developing country per capita GDP to equal that of industrial countries in 1990, beginning in 2050 …

This represents what is perhaps the foundational faith of modern economics: a faith in human adaptability and ingenuity. Especially via the distributed decision making represented by open markets, humans can master almost any circumstances given time.

In short, many economists simply assume that climate change will have little effect on us in the long run, because dagnabit, we’re HUMANS and we can do anything! Whatever happens the future will be just hunky-dory and wealth will increase no matter what we do, climate change be damned.

To which I can only say, clearly such economists are lousy historians. Anybody remember the effects of the Bubonic plague on human societies? The collapse of the Roman Empire and the Dark Ages that followed that collapse? Or more recently the consequences of WWI and WWII on the economies of the world? Catastrophes happen.

We’ve been fortunate in many respects because the effects of the human-made disasters over the last century were offset by the tremendous technological progress our societies generated. However the current science experiment we are conducting by pumping giga-tons of CO2 into our atmosphere each year (please note that 1 giga-ton = 1,000 000,000 tons). Last year, we set a record of 30.6 billion metric tons of GHG emissions. What’s worse is that most of those emissions will continue at or near this this amount for the next decade.

Some experts were hoping that the global recession experienced in 2009 would lead to decreased and more efficient energy use. This does not seem to be the case. The IEA also reports that an estimated 80% of projected emissions for 2020 from the power industry are locked in.

Many experts and global leaders agree that a target of limiting temperature increase to 2°C by 2020 should be set. In order to achieve the 450 parts per million of CO2 required for this scenario, emissions can only reach 32 billion metric tons by 2020. That means that over the next ten years, the global emissions increase must be less than the total increase between 2009 and 2010.

No economist or industry analyst in their right mind would disregard contingent risks when assessing the potential growth or loss of any business enterprise. Yet that is exactly what many economists are doing when the calculate the cost of taking action to cut emissions versus the cost of doing nothing. Economists (not all but many of them) simply refuse to consider of catastrophic consequences resulting from our continued reliance on fossil fuels. A perfect example is Richard Tol, a member of the IPCC and an economist with Dublin’s Economic and Social Research Institute, who refuses to accept that the cost of investing in the reduction of carbon emissions is worth the price.

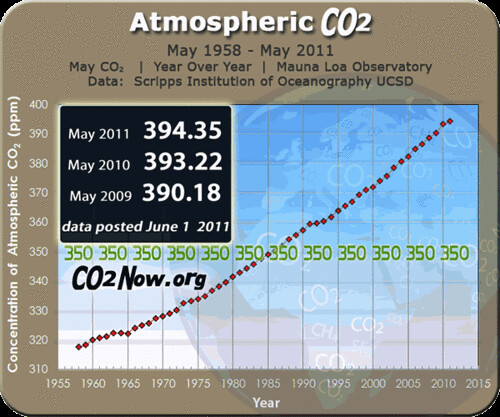

Tol believe that the reducing carbon emission on the cheap is the best way to go (i.e., imposing a carbon tax of no more than 50 cents on every ton of CO2 emitted), even though he acknowledges that his proposal would result in 850 ppm (parts per million) of CO2 in the atmosphere. Most climate scientists, however say our best hope is to increase our current level of CO2 to no more than 450 ppm if we hope to avoid the worst case scenario (and may believe 350 ppm is a much safer level even though it will still create many problems for us silly humans living on earth). As of May, 2001, however, the current level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (as measured by the Mauna Loa Observatory) is 394.35 ppm. Just look at this chart to see how much CO2 emissions have increased since 1955.

Climate modelers have concluded that a CO2 level of 850 ppm (which seems ever more likely considering current trends in emissions) would increase the average global temperature by 2100 by 3.5°C (or about 6.3°F) over the global mean for the year 2000. Climate research suggests that even a 2.0°C rise in global temperatures puts us in the “danger zone” where irreversible changes to our climate will result in catastrophic effects for human, animal and plant life. From the 2003 Assessment of Knowledge ion Impacts of Climate Change:

Above 2°C the risks increase very substantially involving potentially large extinctions or even ecosystem collapses, major increases in hunger and water shortage risks as well as socio-economic damages, particularly in developing countries.

James Hansen, renowned climate researcher at NASA goes even further. He suggests that even a 1°C rise in global temperatures is likely to create massive ecological and socioeconomic impacts with which we are ill prepared to address:

We use paleoclimate data to show that long-term climate has high sensitivity to climate forcings and that the present global mean CO2, 385 ppm, is already in the dangerous zone….Equilibrium sea level rise for today’s 385 ppm CO2 is at least several meters, judging from paleoclimate history….If the present overshoot of this target CO2 [350 ppm, or approximately 1°C above pre-industrial levels] is not brief, there is a possibility of seeding irreversible catastrophic effects.

So how does Richard Tol get away with suggesting a level of 850 ppm of CO2 is manageable? Because he downplays the risk of future impacts and underestimates the benefits of taking serious action to reduce future levels of CO2:

“Tol downweighs future impacts and overstates the lack of affordable options to bring emissions down,” said [Dimitri Zenghelis, Chief Economist of Climate Practice and Cisco Systems]. “Using his assumptions he would also recommend not committing any noticeable investment to counter a known meteor heading for earth, or a devastating global pandemic due in 50 or 100 years, because it is not our current concern.”

The truth is that asking economists to consider the true costs of warming the globe by 2.0°C or 3.5°C versus the cost of preventing such increases is unlikely to be very useful. traditional economists simply cannot accurately predict that far ahead in the future. Heck, they can’t even agree on the causes of, or the solutions for, our current economic crisis. The reason such economists are the wrong people to consult regarding the policies governments should adopt to combat climate change is not that hard to explain. I’ll let a real economist, Eban Goodstein, director of the Bard Center for Environmental Policy and former Economics Professor at Lewis & Clark and Skidmore Colleges, tell you why, however.

Most economists live with a powerful picture … in their heads.

Calamities such as the Great Depression, major regional wars, global epidemics like AIDS, or the recent burst in the global housing bubble, barely put a dent in long-run growth. The default assumption is that capitalism will march relentlessly on, regardless of climate change (or peak oil, or fresh water, or top soil shortages). Sidestepping the issue of whether continued growth enhances welfare, the conventional economists’ position seems well-grounded in historical experience. […]

At the macro level, Integrated Assessment Models develop damage functions very roughly calibrated from sectoral studies of moderate warming, that then reflect arbitrary increases in damages with greater warming. Elizabeth A. Stanton, Frank Ackerman, and Sivan Kartha (2009) point out that because William Norhdaus’s DICE model carries an exponent of two on its damage function, the model has to heat the planet up by 34 degrees F to cut global GDP in half! Increase the damage function exponent to four or five, and DICE makes collapse look somewhat more likely, but by no means inevitable.

In short, they use assumptions that if moderate warming causes X amount of damage to the global economy, than increased warming will only have a slightly higher effect on GDP for example. Yet can anyone here truly believe that the effects of a 34 degrees F increase in global temperatures (i.e., 19°C) would only cut global GDP in half? Even climate deniers might be skeptical of that claim. We are already seeing the effects of extreme weather events increase at our current level of warming and CO2 levels.

We’ve witnessed “500 year floods” that have occurred twice in the past 15 years. Arctic sea ice at its lowest extent in human history. Massive wildfires from Russia to Arizona to Greece. The greatest mass extinction event we have ever experienced. Water resources necessary to keep literally billions of people alive in danger of vanishing within our lifetimes. The die-off of oceanic life. Droughts that threaten our future food supplies.

These are events and risks that economists are not qualified to opine upon. They don’t know the science. Their projections of current trends in the economic costs of climate change tend to assume a straight line increase when in fact we are more than likely experiencing logarithmic growth in the effects of rapid climate change that make their pretty little graphs regarding the economic costs of climate change utterly useless as tools for policy makers.

Back to Eban Goldstein:

To sum up: Economic models that model marginal changes have a hard time grappling with the economics of disaster. That said, academic economists nevertheless have waded in, and do tend to be aware of the limitations of their modeling exercises, providing appropriate caveats in the text. That said, those caveats often disappear from bottom line policy purposes to which studies are put. Thus the projections of continued future economic growth from the IPCC, and Stern.

Guess who understands that climate change is not your ordinary blip on the economists faith in ever increasing economic growth? People who make understanding risk their business. In other words, the insurance industry. Much as I hate those companies, they are far more objective in their assessment of climate change than most economists, and politicians for that matter:

While climate zombies in Congress are lurching in lockstep toward environmental catastrophe, the insurance industry has been scrambling to act. It’s well past time we listened to what they have to say. Insofar as the Republican party is the party of business, they might want to lend an ear as well. […]

The insurance industry is all about risk assessment and capital accumulation. Katrina-like catastrophes lurk on the discernibly warmer horizon, giving insurance companies a real deal incentive to slice against the zeitgeist of denial. […]

Over the last five years, the insurance industry has become increasingly proactive on climate change, in terms of both underwriting and investment. Reinsurance companies – essentially firms that insure the insurers to manage and defray risk – have taken the lead. In September 2007, insurance firms formed ClimateWise in order to reduce economic risk associated with climate change.

That same year, Andrew Castaldi, head of the catastrophe risk unit for the Swiss Re America Corp, testified to the Senate’s homeland security and governmental affairs committee, “We believe unequivocally that climate change presents an increasing risk to the world economy and social welfare.”

In 2008, Ernst & Young – not known for having to peel bark from their sweater vests after intensive treehugging sessions – named climate change the number one risk to the insurance industry. In a 2009 report, Lloyd’s of London warned of climate change contributing to “resource-driven conflicts; economic damage and risk to coastal cities and infrastructure; loss of territory and resultant border disputes; environmentally induced migration; government fragility; political radicalisation; tensions over energy supplies and pressures on international governance”. […]

And this month, while US media fail to consistently connect the dots between weather patterns and climate change, Munich Re – the world’s biggest reinsurer – stated plainly, “weather extremes such as the massive floods experienced by China since early June are due to the advance of climate change.” While acknowledging factors like population growth and rising property values – especially in risk-prone areas – Munich Re wrote, “it would seem that the growing number of weather-related catastrophes can only be explained by climate change.”

Insurance companies aren’t jumping on the climate change bandwagon because they are starry eyed idealists, or economic terrorists, or part of a mass conspiracy existing in Senator Inhofe’s oil soaked brain. As we all know, they are among the hardest of hard headed capitalists. The difference between them and the Oil industry is simple: they don’t have a vested interest in getting people to deny the reality of climate change. Unlike many traditional economists, they don’t see the world through rose colored glasses when it comes to risk assessment. They know a threat to their business model when they see one, and trust me they aren’t supporting the views of climate researchers out of the goodness of their hearts because when it comes to business they don’t posses that organ.

So the next time some right wing dittohead tells you that economists don’t think its worth the cost investing in solutions to reduce CO2, the principal driver of climate change, ask them why insurance companies are so damned concerned? Ask them why they can’t get insurance for wildfires? And ask them why should we rely on economists predictions of the effects of climate change when so many of them couldn’t predict the financial crisis that led to the so-called Great Recession?

Because my friends, as much as I respect economists, they aren’t the experts our policy makers should be looking to with respect to the dangers posed by inaction regarding climate change. Far from it

Great piece, and very extensive in your citations. Particularly spot on is your look at the insurance industry. The insurance industry is to the US what the KGB was to the USSR–they know what’s coming. (The KGB pushed alongside reformist types to install Gorbachev, because they were acutely aware of how thoroughly stagnant Soviet society had become). The insurance industry is also an excellent rebuttal to those who say economic planning is impossible, because it’s precisely how they make their money.

At some level though, (capitalist) economists are clueless about climate change because they have a neat trick to make anything that doesn’t fit their model of growth disappear:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Externality

We don’t calculate the cost, even in strictly economic terms, of climate change, because it doesn’t fit in the price model, such as it is. It’s an “externality.” The cost gets paid, just later on and by people outside the inquiry. You get your tenure or your post at the Cato Institute regardless.

John Bellamy Foster at the Monthly Review is a good go-to scholar for this stuff, if you haven’t read him already.

Thanks for the post and your work generally.

Very nice piece, Steven. A minor quibble on your wording: there are not risks associated with the course of doing nothing (or nearly nothing). There are certainties. Calamaties, great ones with staggering economic and human costs, will happen. The only question is how accelerated the timeline will be.

It depends on your assumptions about spontaneous mitigation efforts (as opposed to planned ones) as to the certainty and the magnitude of the adverse effects.

In the long run, we’re dead. A certainty. Actuarial tables are calculated to predict the risk (likelihood of death) associated with various rating factors. One of those factors is age.

The closer on the timeline and the more certain, the less opportunity for immediate response and remediation. Depending on how elaborate the actions are in order to carry out an immediate response.

The conservative economists and climate “analysts” are not arguing for no levee but for putting in sandbags when and if a risk occurs. And certainly not taking developable land with river views out of flood plains. Or prohibiting “ocean view” properties on barrier islands.

The comment about “externalities” is spot on. It is a methodological problem that some economic-ecological types have recognized from the 1970s. One of the first to take a whack at it was Walter Isard in Ecologic-economic Analysis for Regional Development; Some Initial Explorations with Particular Reference to Recreational Resource Use and Environmental Planning published in 1972.

The problem isn’t a price theory one as much as it is that economic analysis works almost exclusively with quantities (units, volumes, etc.) and dollar-costs. But dollar-costs at any point in time and space are set by some putative market. And that market evaluates costs/prices in terms of the supply that some putative human beings desire (value), the cash they have with which to get what they value, and the supplies of what they value, and the comparative competitive power of the buyer and seller to shape the resulting price. The frame of reference is in terms of what is of value or provided by a single economic actor, human being or corporation. And the results are assumed to be a straightforward aggregate of these transactions. Except that work in the past couple of decades shows that they are not an aggregate but the emergent effect of a network of decisions.

Nonetheless, man is the measure of all things.

The ability to model (predict is really giving it too much credit) effects of global climate change depends on the climate models of the effects on quantities of resources and growth in population. These are not the economist’s bailiwick. So the choice of model results from the climate, agriculture, industrial forecasting, technological guys, and other forecasters is the numero uno important choice in a study.

So what dictates that choice, given several different methodologically sound result sets? Well, a study would likely show that the model selected aligned with the source of funding of the study.

So who is it that is likely to fund studies that minimize the economic impacts of climate change and provide overly optimistic estimates of technological response? Come on, guess who.

And what institutions are they likely to use to fund these studies? Think tanks, university chairs that they have endowed…

And how do the results of these studies get known by the public? Through interviews in various media. Who buys advertising in the media? Hint: Greenpeace can’t afford that much media time.

And economists are not actuaries. Risk is an externality until it is realized as a cost.

So, it isn’t economists in general, it is certain economists who as public intellectuals give opinions way outside their expertise. The classic illustration in Milton Friedman, whose expertise was in how governments manage the money supply and how they can do it better. So Friedman the public intellectual advocates smaller government and government with limited role in the economy. Why? The political concept of “liberty”. Friedman never did research into free, ungovernanced competitive markets. Or he would have known that they tend to either destroy the freedom, destroy the ungovernanced, destory the competition, or destroy the market itself. Dare I say that we’ve seen all of these in the last decade.

Economists, who unsupported by other scholars, pontificate on the cost/benefit of addressing climate change in this way or that are operating outside their pay grade. Which is why the most meaningful results have come from internationally-convened committees of multiple disciplines.

I wouldn’t even trust Paul Krugman to be the sole person making a decision about what solutions to climate change to pursue. Regulations have risks and costs of corruption, pseudo-markets like cap-and-trade can be gamed or not constrained enough to make a difference, direct projects can be squandered.

Your focus on the threats to established business models creating competing communities of scholars is right on target. Which political candidates are the property, casualty, agricultural, and weather hazard insurance companies backing? How about the re-insurers?

When it comes to politics, business owners don’t always actually act in their own interest because of the information that is fed them by their industry (lobbying) associations, the staff of which are part of the Village (or its state equivalent).

You know, re: externalities: I would have been an A student in algebra if I was allowed to say that certain variables are no longer part of the equation. That’s how inane externalities are.

Interesting about Friedman. I knew his general line but never dealt with him biographically. There’s a problem with academic expertise as it works at least in the US, which is that one thrives by making oneself master of a subject so small that nobody can challenge one. There is no place for synthesis, at least if one wants to get ahead. All this is great, if it’s used properly. Obviously, it’s generally not, and certainly not with economic policy.

By the way, I see your comments often and appreciate your thoughtfulness.

But economics is not algebra.

There are in fact things that cannot be priced. The values that shape purchasing preferences come for the general culture; you can only see their effects on the sorts of products actually bought. The regulation that ensures that the market can continue operate without destroying itself is and externality. How do you price the benefits of a register of deeds compared to the MERS system, for example. Integrity of operation is an externality.

All of he ecological processes that do stuff that helps the economy, but do it for free — air and water cleansing, for example — are externalities. The fact that it is free, means that it is an externality as far as the economy is concerned.

The goose that laid the golden egg was an externality. In fact that is a classic fable about not ignoring externalities even if they cannot be quantified. You can quantify the value of the golden eggs (weight x price of gold per unit of weight) but not the value of the goose. And after you kill the goose, you can’t quantify the loss because you don’t know the full lifetime production of the goose that you killed.

The environment is the goose.

This is fundamentally why I call cap-and-trade and carbon tax “pseudo-market” solutions.