You know all those trees burning in the Northwestern United States and Canada? Those are just a small part of the great boreal forests, a/k/a the taiga in Russia, that cover as much as thirty percent (30%) of the earth’s total forests. In 1998, scientists published a study, “Climate Change and Forest Fire Potential in Russian and Canadian Boreal Forests,” which predicted that climate change would bring about significantly greater risks of “forest fire danger levels” in Canada and Siberia, with large relases of carbon into the atmosphere as a result. Seventeen years later, we are witnessing their predictions come true as over just the last five years massive fires have burned millions of acres in Russia, Alaska and Canada.

Millions of acres of forests have burned or are burning right now in the United States alone as I type these words.

Here’s the breakdown: As of Aug. 20, more than 41,300 wildfires have scorched more than 7.2 million acres in 2015, mostly in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. That’s nearly three times the 2.6 million acres that burned nationwide in 2014 and more land area than has burned in any other year over the last decade.

The blazes have consumed so much land this year because of the drought, fueled by record high temperatures during the warmest January-to-July period in history for the region. Partly to blame for the heat is a giant area of warm water in the Pacific known as “the blob” and the rapidly growing El Niño, which could be one of the most extreme on record.

The drought and high temperatures are stressing forests to the point where they can’t fend off the worst effects of wildfire, even in those forests that depend on occasional fires to survive.

Scientists are telling us bluntly that we need to make the protection of these forest eco-systems from the effects of climate change a priority. They claim that current conditions and climate trends have put the survival of these forests at a tipping point from which there may be no turning back.

“Boreal forests have the potential to hit a tipping point this century,” said Anatoly Shvidenko, a researcher scholar with the Ecosystems Services and Management Program at Austria’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). “It is urgent that we place more focus on climate mitigation and adaptation with respect to these forests, and also take a more integrated and balanced view of forests around the world.” […]

[E]xperts say that they are being threatened by warmer temperatures brought on by climate change.

“The changes could be very dramatic and very fast,” Dmitry Schepaschenko, an IIASA representative, told The Canadian Press.

“Although it [the boreal forests] remains largely intact, it faces the most severe expected temperature increases anywhere on Earth. Mr. Schepaschenko said some parts of Siberia are likely to eventually become 11 C warmer. That will bring greater precipitation, but not enough to compensate for the dryness caused by hotter weather. A drier boreal will suffer new diseases, insect infestations and vast wildfires,” The Canadian Press’s Bob Weber reported.

Vast wildfires? Equal to or worse than what we are experiencing this year? More than likely the answer to that question is “yes.” We’ve witnessed a series of ever larger wlldfire seasons in the United States over the last ten years, and this same phenomenon has also been the new normal across the rest of the globe, from Russia to Australia to Indonesia.

Scientists have urged the Canadian government to set aside as a preserve at least fifty percent (50%) of its great boreal forest ecosystems in a last ditch effort to save them.

A group of international scientists is calling for 50 per cent of Canada’s boreal forest to be protected from any type of development, and they’ve outlined their plan in a report released today at the International Congress of Conservation Biology in Baltimore, Md.

The International Boreal Conservation Science Panel (IBCSP) says half the 5.8-million-square-kilometre [diarist note: that’s roughly 1.5 billion acres] forest needs total preservation, because it is the only way to effectively ensure the ecosystem services — like storing carbon and cleaning surface freshwater — are protected. […]

According to the IBSCP, Canada’s Boreal Forest “encompasses the largest blocks of intact forest and wetlands remaining on the planet.”

The IBSCP’s call for conservation comes in the face of mounting industrial pressure on the Boreal Forest. Most of that pressure comes in the form of logging, but other sources of concern to the scientists are the oilsands in Alberta and mineral mining in other provinces.

Unfortunately, it’s an open question as to whether anyone listen to them in a “media climate” that, whether in the interest of “fair and balanced reporting”, or out of the fear of antagonizing some of their largest advertisers, gives equal weight to the opinions of those who spout denialist lies and disinformation as to actual researchers who have collected the data that shows that the climate crisis, one caused by a warming earth brought on primarily by human activity that releases CO2 and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, one about which we’ve been warned would come since Dr. James Hansen testified before the U.S. Senate in 1988, has arrived with a vengeance. And one of the new drivers accelerating the rate at which climate change occurs includes not only the carbon being released by the fires themselves, but also the decrease in carbon absorption by these great coniferous forests in the high northern latitudes.

Drawing on the latest research on forest ecology, the impacts of recent climate change, and studies on projected future climate change, this report shows that between 50 and 90 percent of the existing boreal forests are likely to disappear as a result of a doubling of atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. This doubling is expected to take place over the next 30-50 years, and is likely to create abrupt changes in the Earth’s climate that would result in severe forest decline. The rate of decline is still uncertain, but is likely to be rapid in many regions, and driven by massive fires, insect outbreaks and storms. […]

Serious disturbance of the boreal forest ecosystem can be traced back to an abrupt shift in the global climate in 1976. Since then higher temperatures have sparked larger and more frequent fires throughout the boreal forest, and the number of storms and damaging insect outbreaks has increased. These disturbances have been accompanied by a decline in conifer populations in the southern part of the boreal forest.

Unless atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are quickly stabilized climate-vegetation models predict that large areas of boreal forest will be reduced to patchy open woodland and grassland, resulting in lowered biological diversity and a reduced ability to store carbon.

Studies of the global carbon cycle suggest that boreal forests are not absorbing as much carbon as they did before 1976. As a result, the atmosphere already appears to contain 10-15 billion tonnes of carbon more than it would have if forests had continued to absorb carbon at the pre-1976 rate.

If boreal forests continue to decline, estimates suggest that burning and rotting of boreal forests could contribute to the release of up to 225 billion tonnes of extra carbon into the atmosphere, increasing current levels by a third. This would accelerate the rate of climate change.

Increasing the current levels of carbon in the atmosphere by a third would take us from our present level of roughly 400 ppm of carbon dioxide in our air to over 600 ppm. That, of course, doesn’t take into account all the other sources of increased greenhouse gas emissions (CO2 and methane) from an increased warming in the Arctic. If you wonder why climate scientists, and especially those who study the climate of the northernmost latitudes of the earth, are running around like people with their heads on fire (grim gallows pun intended) those are the reasons.

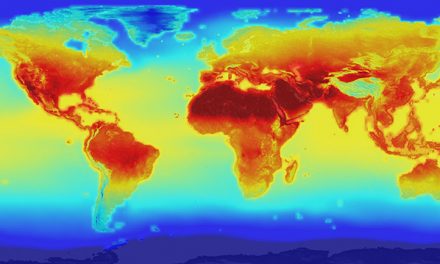

As the far north continues to heat up at a rate no less than double that of the rest of the world, we are in danger not only of losing the many wondrous species of trees, plants and animals that populate these regions, but also of increasing the amount devastation experienced elsewhere in the world from global warming due to the additional massive quantities greenhouse gases that will be released into our atmosphere as these great boreal forest environments disappear. Yet, these are the very regions that loggers and the oil and gas extraction industry want to develop the most. To save the planet we may very well have to stop some of the richest, most powerful multinational corporations on earth from getting their way.