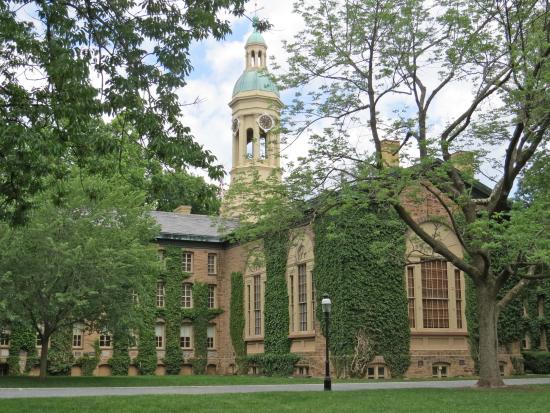

I grew up in a very distorted world during a very strange time in American history. And then I spent the next thirty years gradually deprogramming myself and learning to see with new eyes. My political awareness began in 2nd Grade when we had an election to decide between Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford. I still remember the name of the one girl who supported Ford. The public schools in Princeton, New Jersey weren’t a hotbed of conservatism in 1976. After Ronald Reagan became president, they were even less inclined to support the Republican Party.

One of my early memories is attending a birthday party at Morven, then New Jersey’s governor’s mansion, for the son of Democratic governor Brendan Byrne. When I went to friends’ houses to play, I was typically entering the home of a Shakespeare scholar, an astrophysicist, a mechanical engineer, a senior partner at a major New York law firm, a Near Eastern Studies professor, or an analyst for the CIA. No one chooses their upbringing and I don’t apologize for coming from a privileged background. Plus, there were some large disadvantages to being introduced to the world in what amounted to a disconnected bubble.

In my world, educated people rolled their eyes at Ronald Reagan and had no patience for the Conservative Movement. Where he had some support, it came from those outside of academia among people who commuted to New York to work in advertising or the financial sector. But even among this crew, the support was grudging and apologetic, and more a reflection of displeasure with the presidency of Jimmy Carter than genuine enthusiasm.

Later on, I would learn that nationally, people with four-year degrees supported Reagan and the Republican Party and that the Democrats did better with working class folks. I found this inexplicable at first because it seemed to strongly conflict with my own personal experience. But it’s a fact that remained true well into the 1990’s.

In 1994, 54 percent of white Americans with at least a four-year college degree identified with or leaned toward the Republican Party, according to the Pew Research Center. Just 38 percent associated with the Democratic Party.

With my elite Ivy League town background, I did not have anything in common with the Farmer/Labor backbone of the Democratic Party. But I was also unfamiliar with the values of typical white flight suburban America. The rock-ribbed Republican suburbs of Philadelphia (where I now live) were as foreign to me as Appalachia or the Mountain West.

One result is that I did not really understand the base of either party. I would have to learn that slowly and over a long period of time. In the meantime, the parties changed. The Democratic Party shed its farmer/labor base in stages, beginning in earnest with the passage of NAFTA. In exchange, it began to shore up the support of people more like me.

By the early 2000s, white voters without a degree were drifting toward the Republican Party and white college graduates were going the other way. By 2017, the pattern that Pew identified in 1994 was practically reversed: Just 42 percent of well-educated white voters leaned Republican, while 53 percent preferred the Democrats.

On one level, this was a welcome development. I’d always felt like an outlier in the Democratic Party and I now I felt more at home. But the flip side is that I’d spent a couple of decades learning to appreciate and value the party’s role in representing the working class, the small farmers and coal minors and auto workers and wage employees who didn’t enjoy the privileges I had growing up. I highly valued the party’s position on civil and equal rights from the earliest age, but I came to see its championing of the little guy (whatever his or her race or religion) as part of the same package and equally important.

This story is unique to me, but it’s also a story that is playing out nationally now. As the New York Times points out, inner-ring suburbs are now behaving politically much like the Princeton of my youth. Outer-ring suburbs are now the home of the white flight ethos.

In 2016, those two suburban types fought to a near draw. Mrs. Clinton beat Mr. Trump by 5 million votes in inner-ring suburbs. He countered with a 5.1 million-vote advantage in outer-ring suburbs.

One reason is diversity. My 2nd Grade classroom was filled with people from all over the world. I had classmates I can remember in elementary school from the Philippines, Ethiopia, Vietnam, Denmark, South Africa, Iran, India, and Pakistan. They came from all over the world to attend or teach at an elite university. My closest friends were mixed nationalities (e.g., Swedish/British) or mixed religion (Jewish/Christian) and this was normal for me. This is how Philadelphia’s inner suburbs look now. It’s how my son’s elementary school classrooms look. It’s as if Princeton has grown and expanded, and the Democratic Party has grown and changed as a result.

Yet, that feeling of being in a disconnected bubble has also expanded. It’s as if there’s a whole different America out there outside of the inner suburbs that is inexplicable. How could they support people like George W. Bush or Donald Trump?

I know the feeling because I grew up with it and had to spend so much time trying to understand it. What’s really changed is that highly educated people have become more uniform in recognizing the conservative movement for what it is and rejecting it. But working class white people have come to see the movement as their champion. The coal miners who were among Mike Dukakis’s strongest supporters even as he was getting slaughtered among white professionals are now wearing MAGA hats. I don’t see this as a positive development. I don’t want to see the left abandon the little guy (regardless or race or religion) or see the little guy abandon the left.

But political parties chase votes where they are easiest to find, and the Democratic Party is drifting into a party based more on shared values than shared economic experience. This approach wasn’t viable in the 1980’s and 1990’s, but it gets the party to parity in the country today because of the twin factors of increased diversity and increased solidarity among the highly educated.

But the bubble remains. There’s a whole other America out there that doesn’t share our values and there’s enough of them to gridlock the country and make it ungovernable. I feel like the party is at the beginning point of a journey I began a long time ago. It’s a journey to understand the country as it really is, and what is most important about being supportive of the less privileged and fortunate.

Mike Dukakis still talks about winning West Virginia in 1988, and about the fact that it’s a sign something has gone horribly wrong with the country, and with the Democratic party, that WV is now a solidly Republican state.

This recent article by David Dayen about Stephen Smith and the “West Virginia Can’t Wait” movement/organizing campaign is both a sign of hope, and a sobering warning of how much work it will take for the Democratic party to rebuild its working class base in predominantly white areas of the country: https://prospect.org/power/new-uprising-on-a-country-road-west-virginia/

The parties largely don’t have a say in the matter and structural forces long baked into the cake have forced a realignment. I liked the Jello analogy. It hasn’t fully settled yet, but the ingredients are all floating around and shifting until finally the Jello has settled into a solid.

With regard to the education question, it’s not just that educated voters are shifting towards Democrats, but that more people are college educated. The same trends are observed in U.K. and France. Educated moving to the left in combination with greater educated citizenry.

But Donald Trump has only accelerated what was already there. Hungary had local elections the other day, and what do we see? Urban areas continued to move away from Orbán’s party, as did the inner ring of suburbs, but the rural areas similarly shifted more towards Orbán!

Bernie Sanders is speaking to all segments of this country. I don’t know if this country is smart enough to support him but he’s doing what is needed to reach them all.

Bernie Sanders’s advantage is weird, anti-politics, and disaffected voters tend to support him, resulting in lower third party support, but he might be weaker in the suburbs and lose some House seats. His support among all other demographics won’t look much different from Joe Biden’s, however. See this chart.

And, you know….heart attack. Which would be immediately disqualifying for any other candidate in the race, let alone one of the women.

And you are free to bring it up as a legitimate line of inquiry and the voters can decide.

The average life expectancy of a 75 year old man post heart attack is a little more than three years.

This appears to be a white person issue, where white folks (and white men in particular) are having to deal with racial and gender equality. That means sharing the privileges they have enjoyed for so long.

“Equality feels like oppression for the privileged” is the gist of what someone smarter than me said. What does the “oppressed” white person do? Some recognize their group as the true oppressors and work to dilute white privilege. Others start oppressing harder.

Not surprised that more educated whites have begun breaking hard for the Democrats. Having the scales fall from their eyes, seeing what conservatism has created, applying those dearly purchased critical thinking skills, and realizing there is no home for them in a virulently anti-education, Know-nothing Republican party.

That’s related to what I came to say. The non-college voter population in the US come in two flavors, those with a fairly clear concept of how the economic dice are loaded against them and those without. The latter are mostly white, and blame their disadvantages on a crazed mythology of lost male and white supremacy. The former are mostly not white, and they are an essential element of the Democratic party, not only for the numbers, but also for the way they make Democrats more than just an educational elite, We may be the party of smart people, but it’s not measured by diplomas.

It really is zero sum to some extent. Whites really are losing power. It’s understandable why they would oppose that, any group would. What I fault them for obviously is they are willing to oppress other groups to hold on. That hasn’t been universal though it has been historically common. And educated people as you said jist have a harder time going along with whats needed to do that because they have some degree of exposure to both critical thinking and diversity thanks to their education.

“There’s a whole other America out there that doesn’t share our values”. Values? What values? I see no values being displayed by this incarnation of conservatives.

Environmentalism and civil rights became strong parts of the Democratic platform and Republicans exploited this. Another factor was the end of the fairness doctrine. An economic model developed for right-wing media to which the uneducated were far more susceptible. Add in the fact that Democrats have for years been way behind in basic political messaging skills. The realignment that began with the Voting Rights Act accelerated under Reagan and came to fruition right around 2000. I remember driving around the United States in 1999, from cities to the middle of nowhere, and seeing for the first time, before anyone spoke of a red or blue America, these major divisions. The people in what had become red America were speaking nonsense but they were sincere. They had good hearts and they meant well. In those days I was welcomed even though I was, to them, this weird city guy with different ideas. They shared their goals and fears. The very same things that I was excited about — the road-less rule in national forests, the social openness that was bringing about a slow enfranchisement of minorities — was terrifying to them. And the Democratic party had decided to go Republican-lite with its economics policies, leaving no one to defend the little guy. I didn’t get at the time how corporate interests had made deep inroads into our party but they certainly felt it. What had been the party of the working man in very recent history had entered a corrupt new deal with its corporate patrons.

So many moving parts to this story. Unlike Martin, I didn’t grow up in privilege. My dad was a working stiff. Neither of my parents had attended college (though my mom went for her AA when I was 7 and I became our neighborhood’s first lachke kid). I remember that hard boiled world well and fought my way out of it, attending Johns Hopkins on scholarship. There are elements of that working-class world I miss (the deep interpersonal loyalty that existed between friends) and there are many aspects I don’t miss. At the same time, attending a high school with many wealthy kids from l literally “the other side of the tracks” and then going to this fancy university which was a bastion of wealth and privilege (not quite on par with Princeton but not far off), gave rise to a certain envy (which I still carry). In high school I made friends from the better side of town as I stormed my way into track-one classes. I entered their world but then had to return to my own. Their families belonged to a country club where I carried clubs, polished golf shoes and cleaned toilets. Those kids were moving naturally and easily into the strata of the world that had been prepared for them while I was still having to work so hard and try to scrape my way in. Eventually I gave up and spent eight years drifting from job to job. Eventually I got back on track and attended law school but by then I was operating at a lower level. I went to a pedestrian law school. Was one of the most accomplished students and got through easily but when I go to my Hopkins reunions, I see how so many of my classmates have soared and it brings up feelings of insecurity. On the other side, my children are well placed to enter that world. My daughter had fun in high school in a way I did not and excelled and attended a top five law school. She makes multiples of what I earn. My son is a brilliant software engineer in Silicon Valley living his dream, moving from one start-up to another. He hasn’t yet found his goldmine but I would not be surprised if he did. Meanwhile he’s living a purposeful life that I don’t think will give rise to many regrets. He’s self actualized in a way I was not as I drifted from job to job.

PS: I get the inequities in education because I lived it. The elementary schools on the different sides of my town were day and night different. All the best teachers were on the other side. My school was literally next to a toxic waste dump and was eventually closed while the EPA cleaned up the Superfund site next door. They were worried about the stagnant playground air that I grew up breathing. No one mentions the holes in the chain link fence and how we kids would play in the pretty colored sands. A lot of my elementary school classmates have had cancer. Many have died.

I remember not scoring well initially on standardized tests. I learned to do so. By the time I was in law school I was routinely in the top 1 or 2 percent of anything I took (the LSAT, the AFOQT when I decided I wanted to get into the Air Force and fly planes). But I had to work so hard to develop those skills because those sorts of words weren’t spoken in my home, my parents had so many chores for me that I had to stay up to 2 or 3 a.m. sometimes to get my math homework done and the like. It was a tough, hard slog. And I’ve long felt that I didn’t have the chance to discover my potentials or follow them. I love my work these days and consider myself lucky. But I think it’s a pale shadow of what might have been if I had come up with more advantages.

That said, I’m one of the very lucky ones. So many of my elementary school classmates were just as smart as I and they fell away from their potentials at a very early age. Long before high school. Some have made money but typically as things like plumbing contractors. Those kids didn’t come within a thousand miles of their potential. When I see them at high school reunions, there’s such love. They feel like my brothers and sisters even though, way back when, I was the nerd many of them picked on. We grew up in the same sandboxes and there’s a connection that runs deep.

One more thought: The most profound difference between the sides of town came about in the area of parenting. That’s where huge differences in culture emerged. There were better and worse parents on both sides of the tracks but, generally speaking, the kids of privilege were treated as something important and precious. The parents behaved as if nothing was too good for them. Much was expected of many of them. Their parents assumed they would attend college and do well, whereas on my side of town none of that was a given. A kid might become an assistant manager at Walgreen’s and that was fine. On my side of town, at a more tender age, the style of parenting was way more harsh. Shaming was considered a good source of motivation. We got slapped around quite a bit, and quite openly too. Right in the street, in full view of our friends. Our parents seemed quite proud to display what today would be obvious parental incompetence but it didn’t seem like that to them at the time. It was normal and healthy and good. They had been raised this way and, as far as they could see, it had been good for them so it would probably be good for us too.

On the other side of town, the parents tended to be far better educated. They seemed to have a better sense that abuse was not good parenting. Some were more openly loving than others. Some got great parenting from parents who were present and loving and wonderful. Others were largely ignored and left to be raised by nannies and other caregivers. But even they received a lot of positive messages about their self worth. While we were being torn down they were being built up. If there were exceptions in my neighborhood, families in which there was good parenting, I’m not aware of it. Some were worse than others and my parents were by no means the worst. In fact, as ignorant as they were, I believe they were better than most of their peers. I was shamed plenty and coerced and treated roughly but very little of it involved physical violence. I also was blessed with a very loving and kind grandmother. But for her, I don’t know who I would be. I’m sure I would not have wound up at Johns Hopkins. My father would have been perfectly happy to send me into the military. My mom would have worried but, for either of them, had I just gone to college, that alone would have seemed like success enough. Even a decent job without college would have been enough to make them happy had I been with what seemed to them a good company. In those days there was this sense that a good company would take care of a loyal employee. No wonder so many people feel so screwed over.

Thank for your comment. I appreciate reading about people’s personal experiences.

Not fulfilling my potential is basically the great shame of my life.

I just wanted to offer some appreciation for the posters at this site, because this conversation would not have been possible on the pre-migration (Booman Tribune) site.

Why do you say that you are in a bubble? You live in a cosmopolitan world. People in crappy little towns in West Virginia, where no one ever moves in and most people under 40 who aren’t addicted to oxy moved to Pittsburgh or Washington a decade ago – they live in a bubble.