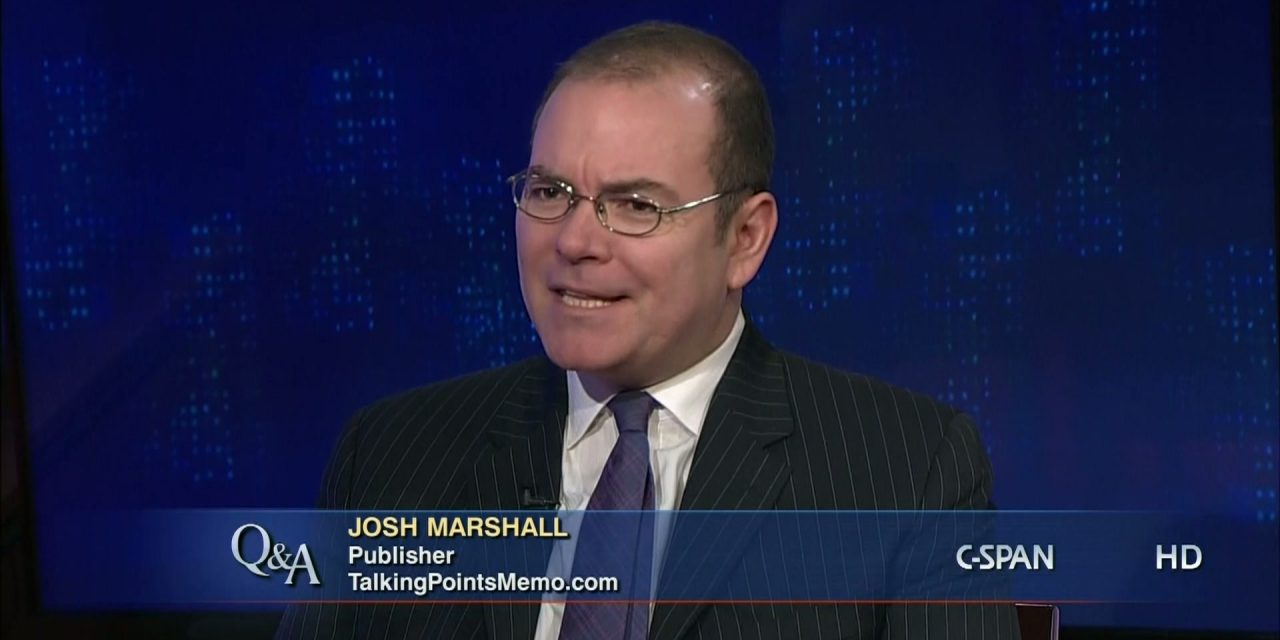

Josh Marshall is correct when he says that Alex Pareene is wrong in arguing that the Senate Democrats wasted time negotiating a bipartisan infrastructure bill. If you’ve been around these parts for very long, you’ll recognize many of the points Marshall hits, because they’ve been made by me time and time again. The heart of the matter comes down to one word (bolded below) in Pareene’s introduction.

What may appear to be an imminent victory for bipartisan deal-making was in fact a drawn-out demonstration of how broken the Senate is as an institution. The Senate (with the White House’s support) wasted months cajoling and rehabilitating a handful of key Republicans, only to pass a smaller version of something Democrats could theoretically have passed entirely on their own.

When you say something could have been done in theory, you really mean that it could not have been done, and yet Pareene has the usage mixed up. It’s fatal to his argument.

Marshall finds it necessary to explain at length why the Democrats did not have the votes to pursue a purely partisan path on infrastructure, but that seems like explaining arithmetic to a college graduate, and Pareene is not an idiot. I suppose it’s Marshall’s way of assigning good faith to Pareene’s argument, but I am not so generous. If someone knows the premise of his argument is crap and he’s still making it, I don’t see why I should spend my time rebutting their premise.

The Senate can fairly be called “broken as an institution,” but the 67-27 cloture vote on the INVEST in America Act did not provide supportive evidence. It showed, somewhat surprisingly, that bipartisanship is still possible even on major, transformative spending bills.

Yes, time is a limited resource, and there were costs to using a lot of it to craft a bipartisan deal. Other important bills were pushed back, and some may ultimately fail for this reason alone. But that’s a matter of setting priorities. In theory, all of Biden’s priorities could get through Congress in eight months, but in reality that was never a possibility. The president chose infrastructure as his top priority and if you don’t like it you should probably make your argument based on that fact rather than the supposedly pyrrhic nature of his victory.

Both Pareene and Marshall seem to agree that the INVEST Act may be the last significant bipartisan bill of Biden’s first term, and they could be correct about that. But a prerequisite for getting two bipartisan bills is getting one. It’s more likely that Biden can succeed in partially unbreaking the Senate now that’s he broken the seal. There’s a group of Republican senators he’s worked with productively and he can go back to them. Senate staffs have cooperated across the aisle and built some trust. A walk of a thousand miles begins with a few small steps.

But you don’t have to believe that Biden has toppled Mitch McConnell’s obstruction levee and that good feelings will soon inundate the land. What’s important is that he had to get 50 votes to do his bigger reconciliation bill, and he didn’t have them. To get them, he had to split his infrastructure plans in two. Any argument that doesn’t acknowledge this is essentially pretending that the Senate isn’t broken.

What we have now is the prospect of what Marshall calls “having your cake and eating it, too.” By this, he means that Biden is on course to get both a major bipartisan bill and the larger wholly partisan reconciliation package. Pareene expresses doubt that the latter bill will ever pass, but aside from some mishap like a Democratic senator falling ill or dying, the path now appears clear.

It’s simply not true that all of this could have been accomplished some other way or that it could have happened on a significantly faster timeline. That’s why Pareene is wildly off the mark when he says, “From a policy perspective, splitting the proposal in two makes little sense.” In the abstract, this is true in the exact same way as it’s true that Democratic senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Simena’s insistence on this process made no “policy” sense. A lot of Republican opponents of the INVEST Act have made the same point, arguing that getting concessions on a small(er) bill only to see them ignored in a larger bill isn’t actually winner’s game.

It’s more coherent to put all infrastructure spending in one bill, but if that was never possible then “policy” coherence is wholly irrelevant. From a political point of view, the two-step process is preferable on almost every level. It split the Republican caucus, it helped Biden prove his case (and keep his promise) for bipartisanship, and it provided some cover for Democratic senators running for reelection in tough states.

If your only remaining argument is that it was too slow and being quicker wasn’t an option, then you have nothing of substance to your complaints.

In the end, Pareene falls back on what happens “if the reconciliation scheme fails,” and that’s fine as far as it goes. If it fails, a lot of time will have been wasted. But this process was a requirement for the scheme’s success, so the logic is twisted here. If a roof requires a crossbeam, you don’t argue its collapse could have been avoided without one.

There’s still much work to be done before any of this becomes law, but so far things are going better than we had any realistic right to expect. Why is it so important to complain then?