Bill Pruitt was one of four producers who worked on the first two seasons of The Apprentice but for 20 years he was subject to a nondisclosure agreement and could not talk about his experience. Now he’s coming out in an article for Slate, and I have to say I’m pretty disappointed in the result. My problem is mainly with the editing of the piece, which I consider criminally negligent. It’s still worth reading and sharing with your MAGA Uncle Jerry, but it could have been so much better.

Pruitt was the last producer hired for the new reality program and he describes his interview for the job. He reveals that the show, as originally conceived, would have a different billionaire host each season, and also that Donald Trump was not the first choice but the only one who accepted. The article is primarily about the sleight of hand that goes into creating any reality show, which Pruitt likens to a magician who specializes as a pickpocket. That’s the first problem with the editing, because it takes an eon to get to any of Pruitt’s direct interactions with Trump, and his experiences with Trump are the main selling point of the piece.

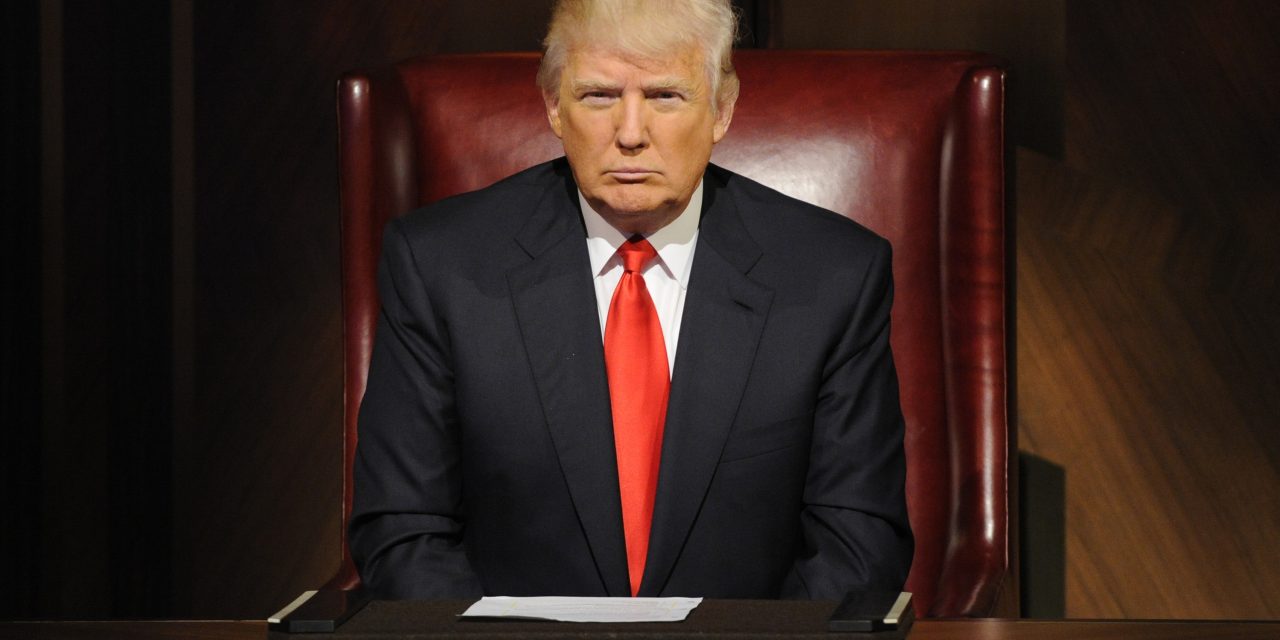

The opening of the article isn’t without value, however, as Pruitt talks about the many hoops they had to go through to present Trump as a successful and competent businessman. There’s the Trump Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City that Trump no longer actually owns which is presented as glamorous even though the sign’s lights are burned out and the carpet stinks. There’s the boardroom they built in the unoccupied mezzanine of Trump Tower which is completely unlike the Trump Organization’s actual boardroom which has chipped furniture. There’s the scenes of Trump flying in a helicopter that’s up for sale because he can’t afford it. And there’s plenty about Trump not being able to remember his lines or the names of the contestants.

There are only three real revelations in the piece, two of which won’t surprise anyone. The first is that Trump bragged that Melania, who was then his fiancee, knew nothing about one of his hideaway residences at the Briarcliff Manor golf course. The implication being that he used it as a love bungalow. The second is that the architect of the clubhouse at Briarcliff Manor was stiffed on the bill and could do nothing because suing would cost more than he was owed.

But the real newsworthy revelation is only revealed a few dozen paragraphs into the piece, and it involves how the winner of the first season was selected. It’s important to understand that what Pruitt describes was captured on film, and also why it was captured on film. The Apprentice was both a reality show and a game show with a prize. In Season One, the winner was given a choice of overseeing the building of Trump International Hotel and Tower in Chicago, managing a new Trump National Golf Course or managing a resort in Los Angeles.

Because the program awarded a prize, it was subject to government oversight arising from the fixing of winners on several 1950’s game shows. Therefore, as a legal precaution, all production meetings related to the “firing” of contestants were filmed and recorded.

The set-up of the first season had George Ross and Carolyn Kepcher, executive vice presidents for the Trump Organization, advising Trump on which contestant deserved to be eliminated at the end of each episode, and this was first discussed off-film in these recorded production meetings. Here’s Pruitt’s account of what happened in the production meeting for the final episode, beginning with a description of the two finalists and the performance of their tasks.

Trump goes about knocking off every one of the contestants in the boardroom until only two remain. The finalists are Kwame Jackson, a Black broker from Goldman Sachs, and Bill Rancic, a white entrepreneur from Chicago who runs his own cigar business. Trump assigns them each a task devoted to one of his crown-jewel properties. Jackson will oversee a Jessica Simpson benefit concert at Trump Taj Mahal Casino in Atlantic City, while Rancic will oversee a celebrity golf tournament at Trump National Golf Club in Briarcliff Manor, New York.

…Both Rancic and Jackson do a round-robin recruitment of former contestants, and Jackson makes the fateful decision to team up with the notorious Omarosa, among others, to help him carry out his final challenge.

With her tenure on the series nearly over, Omarosa launches several simultaneous attacks on her fellow teammates in support of her “brother” Kwame. For the fame-seeking beauty queen, it is a do-or-die play for some much-coveted screen time. As on previous tasks, Ross and Kepcher will observe both events.

The key here is that the winner must be decided in some kind of fair process. In fact, each prior episode, which only produced a loser, required a producer “to equitably share with Trump the virtues and deficiencies of each member of the losing team” in order to render “a balanced depiction of how and why they lost.” Likewise, for the decision on who should be declared the season’s winner, a process was set up for deliberation. Here’s how that looked:

When the tasks are over, we are back in the boardroom, having our conference with Trump about how the two finalists compare—a conversation that I know to be recorded. We huddle around him and set up the last moments of the candidates, Jackson and Rancic.

Trump will make his decision live on camera months later, so what we are about to film is the setup to that reveal. The race between Jackson and Rancic should seem close, and that’s how we’ll edit the footage. Since we don’t know who’ll be chosen, it must appear close, even if it’s not.

We lay out the virtues and deficiencies of each finalist to Trump in a fair and balanced way, but sensing the moment at hand, Kepcher sort of comes out of herself. She expresses how she observed Jackson at the casino overcoming more obstacles than Rancic, particularly with the way he managed the troublesome Omarosa. Jackson, Kepcher maintains, handled the calamity with grace.

“I think Kwame would be a great addition to the organization,” Kepcher says to Trump, who winces while his head bobs around in reaction to what he is hearing and clearly resisting.

And here’s the big reveal of the article:

“Why didn’t he just fire her?” Trump asks, referring to Omarosa. It’s a reasonable question. Given that this the first time we’ve ever been in this situation, none of this is something we expected.

“That’s not his job,” [showrunner Jay] Bienstock says to Trump. “That’s yours.” Trump’s head continues to bob.

“I don’t think he knew he had the ability to do that,” Kepcher says. Trump winces again.

“Yeah,” he says to no one in particular, “but, I mean, would America buy a n— winning?”

And there you have it. One the first season of The Apprentice, Trump decided to make the white contestant the winner irrespective of any objective or fair process that was in place to guide his decision. And he made that decision because he didn’t think America would like it if the black contestant won.

Pruitt ruefully describes the non-reaction in the room.

Bienstock does a half cough, half laugh, and swiftly changes the topic or throws to Ross for his assessment. What happens next I don’t entirely recall. I am still processing what I have just heard. We all are. Only Bienstock knows well enough to keep the train moving. None of us thinks to walk out the door and never return. I still wish I had. (Bienstock and Kepcher didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

Afterward, we film the final meeting in the boardroom, where Jackson and Rancic are scrutinized by Trump, who, we already know, favors Rancic. Then we wrap production, pack up, and head home. There is no discussion about what Trump said in the boardroom, about how the damning evidence was caught on tape. Nothing happens.

I am not a lawyer, but I assume that Kwame Jackson, the black Goldman Sachs broker who was the runner-up, could have successfully sued everyone involved in producing Season One of The Apprentice. Also, since amendments in 1960 to the Communications Act of 1934 “prohibited the presentation of scripted game shows under the guise of a legitimate contest,” I believe Trump exposed the producers, including himself, to criminal prosecution.

Yet, Trump’s casual racism, coming as it did at the very end of the process, was overlooked and covered up, all in the interest of saving the project. Pruitt doesn’t believe the video evidence will ever be revealed, and perhaps he’s correct about that, although a law suit could produce it through discovery requirements.

When you think about the impact the Access Hollywood “Grab ‘Em By the Pussy” audio tape had on the 2016 election, it’s easy to envision how a video tape of Trump using the word “nigger” in an Apprentice board room might reverberate in 2024. Hell, Trump might even assign a fixer to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Absent the video emerging, the best we’ll get is this account from Pruitt, and that gets to my overall dissatisfaction with the piece. It’s not just that the lede was buried, but Pruitt comes off as a run-of-the-mill critic of Trump rather than as a serious person hoping to share vital and important information with the voting public. Pruitt reveals the existence, at least at one period of time, of indisputable evidence of Trump’s exceptional racial animus against blacks. But it’s almost hidden among a more general tirade against Trump’s character and a kind of confession that The Apprentice was responsible for electing Trump by presenting a totally misleading and favorable impression of him and his capabilities.

These are two different, though related, issues. A better editor would have recognized that one is opinion and one is reporting. One is available from countless other sources who’ve had firsthand behind the scenes experience with Trump’s boorish stupidity, and the other is the existence of something potentially determinative of the winner of the November presidential election.

To me, the story is “There’s a video tape of Trump using the n-word, how can we get it?”

There’s another story about how The Apprentice shaped public perceptions of Trump and made him a viable presidential candidate. That story is worth telling too, but we shouldn’t expect it to matter too much in the big picture. Maybe Pruitt will find a better editor or a media advisor to better guide him to having the impact he clearly wants to have. I can tell he wants redemption for not speaking up in that production meeting and for his role in deceiving the public about Trump. He won’t get it from this poorly edited article, but he can keep trying.

As for Kwame Jackson, the ball is in his court. I think he should go to court and try to get that tape.

What’s the chance that the tape hasn’t been destroyed already? It doesn’t just make Trump look bad, it makes the entire production look bad. It may have been filmed as a legal precaution, but 20 years later, the only precaution anyone involved would have would be to destroy it.

The QuickBooks Amazon Integration online streamlining Your finance management by automating transactions, inventory updates, and sales tracking. This integration enhances efficiency by syncing data seamlessly between platforms, reducing manual errors and saving time on reconciliations. Businesses gain real-time insights into cash flow, expenses, and profitability across Amazon channels, enabling informed decision-making. Automated reporting simplifies tax filings and financial analysis, ensuring compliance and accuracy. With streamlined operations, businesses can focus more on growth strategies and customer satisfaction, leveraging the combined power of QuickBooks’ robust accounting features and Amazon’s extensive e-commerce platform.