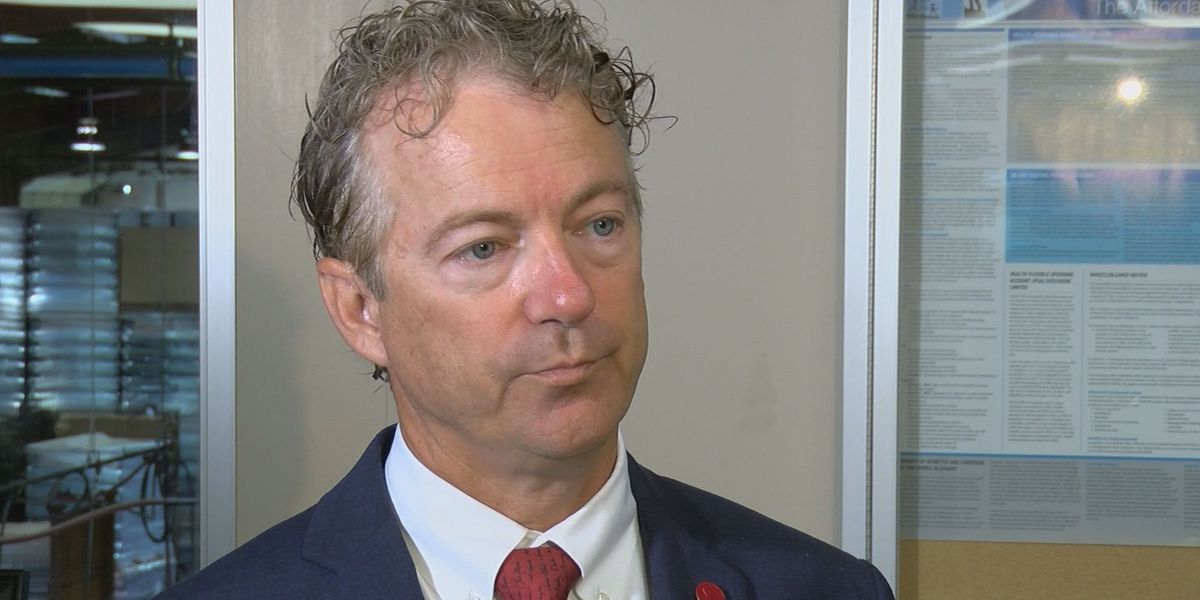

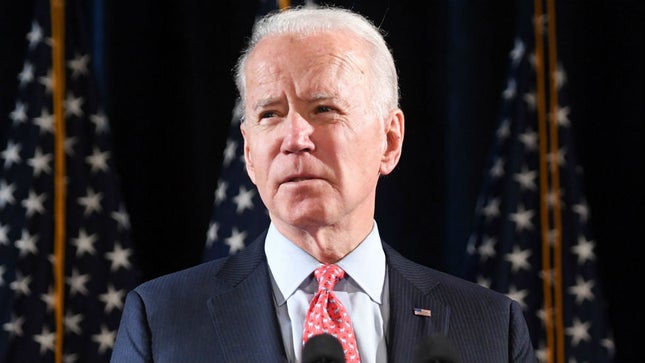

One of the more provocative takes I’ve seen since the election is from The Editors at The Drift. I think it’s unfortunate that they decided to open their piece with a prolonged savaging of Joe Biden, going all the way back to his 1988 campaign. It’s not that I think some of their critique isn’t valid, nor that it doesn’t fit with the overall construction of the article. Rather, it probably causes too many people to just stop reading, including the people who would most benefit. I know I almost did, mainly because I’m just in no mood to see Biden taken to the woodshed. He’s done what he could, and if it turned out tragically for him and for us, I can’t fault the man for giving it his best shot.

What I liked most about their take was that it comes from a pretty far left point of view, but every time I thought they were slipping into the same old boring and tired left-wing critiques of the Democratic Party, they seemed to pull the argument out of the fire. The regular chestnuts are all there, Ukraine and Gaza and the suppression of student protests, elite condescension and sanctimony, overplaying the threat of Trump, over-reliance on abortion as an issue, emphasizing Harris’s record as an incarcerator, campaigning with ex-Republicans like Liz Cheney, shying away from the defense of the Trans community, cozying up to crypto.

But these arguments are not made in the typical lazy way, nor presented as the sole or even primary reasons for defeat. Instead, they’re layered brick by brick to explain why the sum total wasn’t persuasive to lots of traditional or gettable Democratic voters who turned up their nose at Harris not simply because of the “price of eggs,” but because the there wasn’t enough contrast and there wasn’t enough flavor.

Trump has also worked hard to build an edge among loosely or nonpartisan Americans, embracing his identity as the candidate of Joe Rogan, Tulsi Gabbard, RFK, Jr., and the artist formerly known as Kanye West. The “weird” demographic — youngish, heavily male, surprisingly multiracial, hyper-online, alienated and distrustful — has clearly found a home in the Trump movement. He is, after all, weird in his own way: a post-decorum politician, swaying to Ave Maria and extolling Arnold Palmer’s penis. For wide swaths of the population, Trumpism has become the default political ideology, where those without a strong reason to arrive at some rival set of principles inevitably wind up. Why wouldn’t it be? The Democrats have nothing to offer as an alternative but a simulacrum of MAGA politics stripped of the libidinal pleasures of rage and transgression, like the caffeine-free version of Trump’s favorite beverage, Diet Coke.

In fact, The Editors have a message for far-left critics who think this problem is easily solvable with some Bernie Sanderseque messaging:

It might be pleasant to imagine that disgust at Harris’s rightward turn was at the root of her underwhelming performance — that voters stayed home or flocked to Trump because they saw him as offering an alternative. That is the diagnosis many left-wing commentators have arrived at in the aftermath of the election, just as they did four years ago, to explain why Biden squeaked past Trump by a much smaller margin than expected, even amid the perfect storm of Covid shutdowns. It implies a relatively optimistic short-term prognosis, all things considered: the American people voted against the failed Democratic establishment more than they voted for Trump; if next time we can finally succeed in nominating a true left-wing critic of the establishment, in the vein of Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, those voters will happily abandon Trumpism for authentic populism. There were, to be sure, plenty of votes cast against the Democrats in this fashion, like in the Arab American community of Dearborn, MI, which turned out overwhelmingly for Rashida Tlaib and by a thin margin for Trump. And we certainly wouldn’t mind if a reconstructed Democratic Party elevated a socialist firebrand as its next leader, though we aren’t holding our breath.

But there’s a clear element of delusion in the belief that despite strong showings in three presidential elections over nearly a decade, including two victories, “real” support for Trump remains confined to a small coterie of lunatics. Trump is the center of gravity of American politics.

And Trump is the center of gravity for reasons the Democratic Establishment has misdiagnosed:

The Biden-Harris administration made the fatal mistake of assuming that in vowing to “Make America Great Again,” the Trumpist movement channeled a widespread nationalistic mood, a longing to re-center American identity in our politics. This was the moderate complement to the wishful thinking of the Sanders left. It saw authentic Trumpism as a shallow reservoir, joining streams of discontent that could be rechanneled by Democratic politicians — except the discontent it imagined was not rage at economic elites but frustration with the “divisiveness” of liberal identity politics and the culture warring of the 2010s. Democrats could vanquish Trumpism, then, by expelling “wokeness” and replacing particularist rhetoric about race and gender with pieties about American unity. “Freedom” became the campaign’s catchphrase.

Here we see their strongest analysis, as it gets to the heart of the weakness in the Democratic coalition:

The Democrats bet the farm on the idea that a desire to defend the shared traditions and symbols of American democracy could transcend profound divides of class and ideology. America, as an ideal, was supposed to smooth over all the contradictions in the coalition. It was how they’d hold the Blue Wall in the Rust Belt while making inroads into Romney-voting Sun Belt exurbs; fundraise in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street while walking picket lines and strengthening labor law; keep the former neocons on their side while reassuring anti-war activists and Arab Americans that they were committed to peace in the Middle East. Everyone would put aside their differences for the sake of America. But “America” in this sense is, indeed, over.

And here we see the argument come to its conclusion, albeit not without raising some serious questions:

…the Biden and Harris campaigns clung stubbornly to the conviction that Trumpian anti-Americanism was pushed by an aberrant fringe, and for that reason would repel good, normal, healthy voters (even registered Republicans, even people who voted for Trump the first two times). This judgment was wrong. The core claim of the Trump campaign — that America is something that existed in the past and may exist again in the future, but that doesn’t have much integrity or coherence in the present — captures something essential about many people’s experience of social reality today. The political theorist Benedict Anderson famously argued that nations are “imagined communities,” and it is hard to sustain an imagined community of America’s diversity and scale in the face of extreme economic inequality; the fracturing of the media monoculture into a bewildering patchwork of social media platforms, podcasts, streams, and cable news networks; and the decimation, exacerbated by the Covid pandemic, of offline social relationships and community institutions. Under such conditions, it is easy to suspect that anyone who insists we’re all in this together is just trying to rip you off — a suspicion that Trump is especially adept at vocalizing.

My first reaction to this is that they’ve captured something essential to understand about how Trump’s success is directly related to the fragmentation of our culture and decline of real world civic engagement. But, while I can agree that misdiagnosis goes a long way toward explaining why Harris lost, I can’t agree that the effort to overcome this fragmentation was wrong.

If an America rooted in common purpose, strong institutions, the rule of law and basic decency is “in this sense, indeed, over,” that doesn’t mean it wasn’t worth fighting for. It also seems like a perfectly sensible and defensible strategy for smoothing “over all the contradictions in the coalition.” It came close to working, and whatever happens with our government, and whomever runs it, we’ll always be better off with strong institutions and respect for the rule of law.

But re-litigating the past is of less interest than planning for the future. As you might expect, The Editors see opportunity:

Working-class discontent, to the extent it got a political hearing, expended itself in a vain struggle for position in the Democratic Party of Clinton and Obama. Now those days are over — for worse and, with any luck, for better. While working-class “realignment” (or, more accurately, de-alignment, since exit polls indicate a fairly split working-class vote) raises the disturbing possibility of MAGA victories for years to come, it was also a necessary development if any radical alternative to the two capitalist parties was ever going to acquire a mass basis. Perhaps that is not much reason for hope, in the end. But it is reason to contest the Democrats’ outrageous sense of entitlement to their base’s loyalty; to construct an alternative that can block the Republicans’ attempt to reinvent themselves as the party of the multiracial working class; to cultivate leaders who don’t brag about their IQs and insult voters’ intelligence; to replace resentment in our politics with solidarity; and to insist on a radical reinvention of our corporatized, consultant-infested political life. Reason, in short, to try.

Working class discontent is unlikely to go away under a Trump administration. The same can be said more broadly about rural and small-town discontent. Breaking and weakening our institutions won’t repair the elite’s reputations, but it may lead many to value what they’ve lost. The Democrats might not have to make any adjustments at all to reap the benefits of buyer’s remorse in the next midterm elections. But they can’t win back the genuine trust and loyalty of the working class until they get serious about what has really been driving discontent.

To me, this has been primarily a result not of immigration, globalization and trade deals, but of the lack of antitrust enforcement that began under Jimmy Carter in the 1970’s. It has hollowed out America, destroyed entrepreneurial opportunity, led to vast regional inequality, and killed the American Dream for much of the country. The Biden administration was actually excellent on these issues, but progress takes time and their messaging was terrible, in part because the media is owned by monopolists and in part because the party still wanted to court Silicon Valley and Wall Street. In truth, making implacable enemies of those forces in this election probably would have led to an even worse outcome. They print ink by the barrel and control our airwaves.

There aren’t neat and pat answers, but I have been saying for years that when left-wing populism withers, right-wing populism fills the void. And right-wing populism always takes the form of fascism. At a time when belief in our institutions is at all time low, this was fatal.

And that gets to my last question. Is this fatal?

Is there a comeback from this? Or does it all fall now? There’s a real possibility that the door has been kicked in and all that remains is for the walls to collapse.

But one thing I’m sure about is that there’s a yawning void of left-wing populism in our rural areas, small-towns and even in our cities. It’s showing up now in how education level is among the best predictors of voting preference. The Democrats tried being the upholders of the system, the adults in the room. It almost worked. But since it failed, we have the very fascist takeover I predicted for all these years. Even David Brooks sees this now.

I don’t agree with everything the Editors wrote in this piece, but I still see it as essential reading for anyone who wants to understand where we are and how we might get out.