This is the second in the four-part series on my visit to Heifer International projects in Gicumbi District in Rwanda. Crossposted from Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the Planet blog.

Holindintwali Cyprien is a 40-year old farmer and livestock keeper in Gicumbi District, outside of Kigali in Rwanda. But he hasn’t always been a farmer. After the genocide in the 1990s, he and his wife, Mukaremera Donatilla, 40, were school teachers, making a about $USD 50.00 monthly. Living in a small house constructed of mud, without electricity or running water, they were saving to buy a cow to help increase their income. And when Heifer International started working in Rwanda almost a decade ago, Cyprien and Donatilla were chosen as one of the first 93 farmers in the country to be Heifer beneficiaries. Along with the gift of a cow, the family also received training and support from Heifer project coordinators.

Holindintwali Cyprien is a 40-year old farmer and livestock keeper in Gicumbi District, outside of Kigali in Rwanda. But he hasn’t always been a farmer. After the genocide in the 1990s, he and his wife, Mukaremera Donatilla, 40, were school teachers, making a about $USD 50.00 monthly. Living in a small house constructed of mud, without electricity or running water, they were saving to buy a cow to help increase their income. And when Heifer International started working in Rwanda almost a decade ago, Cyprien and Donatilla were chosen as one of the first 93 farmers in the country to be Heifer beneficiaries. Along with the gift of a cow, the family also received training and support from Heifer project coordinators.

Today, they’ve used their gift to not only increase their monthly income–they now make anywhere from $USD 300-600 per month–but also improved the family’s living conditions and nutrition. In addition to growing elephant grass and other fodder–one of Heifer’s requirements for receiving animals–for the 5 cows they currently own, Cyprien and Donatilla are also growing vegetables and keeping chickens. They’ve built a brick house and have electricity and are earning income by renting their other house.

Although Heifer trained them how to collect water with very simple technologies using plastic bags, Cyprien took the training a few steps further and installed his own concrete tank. In addition, Cyprien has enough money to invest in terracing his garden to prevent erosion, a necessary farming practice in this very hilly area.

And today, Cyprien is going back to his roots and making plans to teach again–this time to other farmers. He wants, he says, “the wider community to benefit from his experience.”

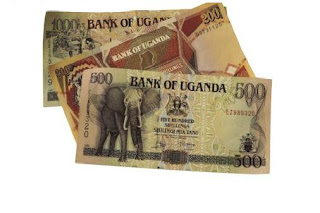

Ready for a math nightmare — every US Dollar is 1,800 Ugandan Shillings! Here’s a test for you: if something costs 51,450 shillings — what is that in US dollars? (No cheating with a calculator…)

Ready for a math nightmare — every US Dollar is 1,800 Ugandan Shillings! Here’s a test for you: if something costs 51,450 shillings — what is that in US dollars? (No cheating with a calculator…) We also tried the local beer — called Club — which reminded me of Budweiser (no offense to to Dani’s home state of Missouri).They have a darker local beer aptly called “Nile” which we will try before leaving. Oh, and for some reason Smirnoff is not only the vodka of choice — but those little Smirnoff Ice wine coolers are ubiquitous in local hands…

We also tried the local beer — called Club — which reminded me of Budweiser (no offense to to Dani’s home state of Missouri).They have a darker local beer aptly called “Nile” which we will try before leaving. Oh, and for some reason Smirnoff is not only the vodka of choice — but those little Smirnoff Ice wine coolers are ubiquitous in local hands… I can’t complain about the toilets (mostly clean, toilet seats almost everywhere in Kampala, but almost nowhere outside the city) — mostly because Uganda offered me my first hot shower since landing in Ethiopia!

I can’t complain about the toilets (mostly clean, toilet seats almost everywhere in Kampala, but almost nowhere outside the city) — mostly because Uganda offered me my first hot shower since landing in Ethiopia! Recovery is a word you hear a lot in Rwanda. From public service announcements on television to billboards—it’s the motto for a place that just 15 years ago was literally torn apart by genocide. More than 250,000 were murdered in 1994 as ethnic strife turned neighbor against neighbor in one of the bloodiest civil wars in African history.

Recovery is a word you hear a lot in Rwanda. From public service announcements on television to billboards—it’s the motto for a place that just 15 years ago was literally torn apart by genocide. More than 250,000 were murdered in 1994 as ethnic strife turned neighbor against neighbor in one of the bloodiest civil wars in African history.