The Haymarket Tragedy and the 8 Hour work day

The People of the State of Illinois

vs.

August Spies impld. &c.

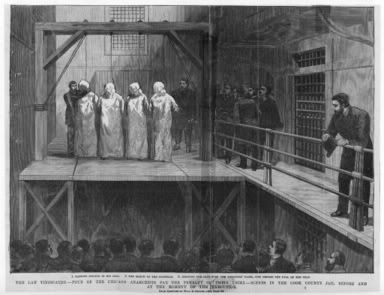

18803 Indictment for MurderTherefore it is ordered, and adjudged by the court that the said defendant August Spies be taken from the bar of the Court to the common Jail of Cook County from whence he came, and be confined in said Jail in safe and secure custody until the third day of December A. D. 1886 and that on said third day of December between the hours of ten o’clock in the forenoon and two o’clock in the afternoon the said defendant August Spies be, by the Sheriff of Cook County according to law, within the walls of said Jail or in a yard or enclosure adjoining the same hanged by the neck until he is dead, dead.

And so it was for all of the convicted, save for one:

August Spies-Death-Executed Michael Schwab-Death-Commuted to Life in Prison

Albert Parsons-Death-Executed Samuel Fielden-Death-Commuted to Life in Prison

Adolph Fischer-Death-Executed Louis Lingg-Death-Committed Suicide

George Engel-Death-Executed Oscar Neebe-15 years in Joliet Penitentiary

The event that lead up to, but didn’t culminate with these sentences, is known around the world as the Haymarket Tragedy, or Riots. I think it should be called the Haymarket Murders. The trials of these men, and the subsequent execution’s of four of them, for allegedly throwing a bomb into a group of policemen, was so tainted and contrived that John Peter Altgeld pictured here , the new Governor of Illinois pardoned the remaining three in 1893. One of the original convicted men, Lingg, had long since committed suicide in his cell, before his execution could be carried out, by biting down on a blasting cap.

Citing his reasons for the pardon , Altgeld wrote:

“The deed to sentencing the Haymarket men was wrong, a miscarriage of justice. And the truth is that the great multitudes annually arrested are poor, the unfortunate, the young and the neglected. In short, our penal machinery seems to recruit its victims from among those who are fighting an unequal fight in the struggle for existence.”

Isn’t that the truth, then and now?

The struggle for the 8 hour work day began long before the Haymarket tragedy and it lasted well beyond the convictions of these men. The reaction to the bombing and and killings of these men set these efforts back decades. In fact, in the U.S., it wasn’t until 1938 that the 8 hour workday was made law through the Fair Labor Standards Act, a result of the New Deal . In Chicago and around the country there was a brutal police and government crackdown on labor unions, socialists, and anarchist organizations.

In the second half of the 19th Century, Chicago, like many large American cities, was a center for industry and an important hub for transporting goods to the west. It’s industry was built on the backs of poor workers though. Many, even most, were immigrants, willing to work for less, if it kept their families fed and housed. In 1850 half of all of Chicago’s people were foreign born and throughout the rest of the century the number of foreign born residents remained above 40%. Increasingly however, workers became organized as a means to counter the power held by business owners and stockholders who saw no reason to obey labor laws. The eight hour work day had already been made into law by the Illinois legislature in 1867, but it was almost universally ignored by business owners because it was unenforceable. Workers were typically forced to work for 12, 14, even 16 hours a day, with little to show for their labor at the end of the week.

The U.S. Census report, of 1886, PDF, shows an average pay of $1.86 a day across all industries, and a total of 807 strikes and lockouts. Of course many workers were paid far less and frequency of payment varied widely. Many wages were paid in goods and services and boarding as well. This is the origin of the term “I owe my soul to the company store”. Families often found themselves indebted to the companies they worked for when they were forced to buy their necessities from employers who overcharged for goods, with wages too low to ever repay the debt or allow a worker and family to get out of the situation. Circumstances like these though, were more often found in rural areas where there were few, if any choices for purchasing necessities.

Workers then became increasingly radicalized in their efforts to bring about fair labor practices. Anarchist’s like August Spies and Albert Parsons found common cause with less radical groups on the left like Socialists, Communists, and organized labor in general. Though their goals differed widely outside of labor issues. Spies, a German immigrant, and Parsons, an American, were both editors of radical daily publications in Chicago.

Spies wrote for the Arbeiter-Zeitung , and Parsons, the Alarm , the English language version of the Arbeiter. Spies’ paper frequently advocated violence as a means of self defense against violent police tactics.

They maintained that although they did not believe in violence for its own sake, armed action in self-defense against this authority was necessary. To adopt such a tactic would be to speak the only language the existing order understood.

The Anarchists and their writings openly called for the use of dynamite as a weapon of choice. This fact would prove to be pivotal during the trial as these publications were entered as evidence, though no connection was ever made or proved that Spies or any of the other defendants were actually the one who threw the bomb into the police ranks.

On May 1st, 1886 strikes were held all across the country in support of the 8 hour workday. Parsons and his wife Lucy Parsons , and their two children led a crowd of 70 to 80 thousand strikers along Michigan Avenue. Chicago’s was the largest crowd, with 350 thousand strikers nationwide, and is regarded as the first May Day Parade. 45 thousand marched in New York, 32 thousand in Cincinnati, and thousands more in many other cities. Business owners became alarmed and regarded these strikes as a sign of a coming revolution and violence. Though police and company paid strike breakers were brutal in their reactions to strikes in general, these events set in motion an unprecedented crackdown on workers and their organizations.

On May 3rd, Spies, as was often the case, was called upon to make a speech at the Haymarket in support of the May 1st nationwide strike. His speech was given near the McCormick Reaper Works,

where striking workers had been locked out since February. During the speech part of the crowd moved to the Reaper Works, , and confronted scabs and police. Even as Spies cautioned them to use restraint. During the confrontation police opened fire on the crowd, including women and children, killing two and injuring many others. Spies and those who remained with him could hear the firing and commotion from where he was. Leaving to see what was happening, he was enraged to find that the police had opened fire on the crowd. Later, during his trial, he recalled how he felt:

“Well, as a matter of course, my blood was boiling, and I think in that moment I could have done almost anything, seeing men, women and children fired upon, people who were not armed fired upon by policemen.”

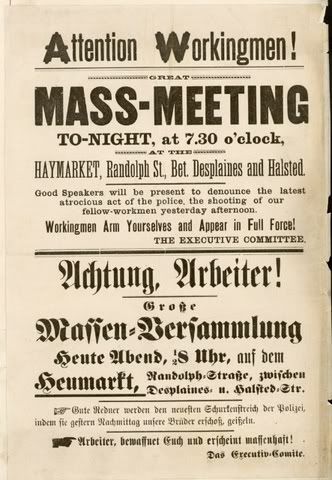

Later that evening Spies wrote a fiery, outraged call to protest the killings on the evening of May 4th. As he was but one of several editors at the Arbeiter, he claimed he wasn’t aware that another editor had added the words “Revenge” and “Workingmen arm yourselves and appear in full force

” to his editorial before it was printed and dispensed.

This was also pivotal in his trial, as the prosecutor used it as evidence that Spies and the others were bent on violence and confrontation. From transcripts of the trial and cross examination of Spies:

This is the circular containing the line “Workingmen arm yourselves and appear in full force?

A Yes sir.

Q That line was in the circular when it was brought to you, was it?

A It was.

Q Will you state what you did, if anything with reference to the circular?

A May I state what I told the person?

Q State briefly what occurred?

A I told the man that if that was the meeting which I had been invited to address–

MR. GRINNELL: That is stating what you said. He asked you to state what you did?

A It is very difficult to state that without–

MR. BLACK: Saying is sometimes doing. This is stating what he said to the man in effect.THE WITNESS: I said to the man “Is this is the meeting which I have been invited to address, I shall certainly not speak there.” He asked me why, and I told him that that line that it was on account of that line. He said that the circulars had not been distributed, and I told him if that was the case and he would alter the circular, take out that line, then it would be all right; and Mr. Fischer was called down I believe at that time, and he sent a man back to the printing office and as much as I know had the line changed.

Q The line was taken out?

A Well, so far as I know I struck out the line before I handed it to the compositors to put in the Arbeiter Zeitung.

Q Do you know of any of the circulars being distributed with that line after that time?

A My knowledge is, as far as my knowledge goes, there had none of those circulars been distributed at all.

Q I will ask you if you know of a large package of them being brought from the printing office to the Arbeiter Zeitung office directly after the order to change the line was given?

A That I don’t know.

Q You didn’t see that personally?

A I can’t swear to that, no sir.

Q Do you remember who the party was that brought in that circular, and took it back with the line stricken out?

A The man has been on the–

Q Greunberg?

A Greunberg or Gruenbog-I don’t know whichI have seen the man. I know him but I don’t know his name.

Q There was but one occurrence of that kind that day that you know of?

A That is all.

Q And he was the only party?

A Yes.

Q It was on that occasion Fischer was called down and by agreement the line was stricken out?

A Yes sir.

On the evening of the 4th, Spies and his brother Henry went to the Haymarket Square

looking for the meeting he’d been invited to speak at. Finding few people gathering, he went about calling those he found to gather around an empty wagon that he could use as a platform. He was joined by Schwab, Parsons and Fielden on the wagon. Spies said later that he was disappointed that so few had come to listen in light of the events of the day before. He estimated the crowd at about 2 to 3 thousand. It was a peaceful gathering as it turned out and even the Mayor of Chicago, Carter Harrison attended, leaving near the end of the speeches, convinced there was no cause for alarm, or need for police, as he deemed the meeting a peaceful one. Shortly after the Mayor left, and as the speeches were winding down, John Bonfield, the Inspector of Police, Chicago, led a large contingent of officers, 180, the short distance from the Desplaines St. Police Station to the Haymarket, where he confronted the speakers on the wagon. I’ve found so many differing stories about what happened during this whole time that it’s important to read the transcripts from the trial to get a real sense of how each event unfolded and contributed to the final violent culmination at the Haymarket.

From Bonfield’s testimony:

What did you do in the evening? Why and how did you come to rendezvous at that particular place that night?

A Sometime during the day of May 4th our attention was called to a circular calling for a meeting at the Haymarket between Desplaines and Randolph streets on that evening.

(Contents of the circular objected to by counself for defendants.)

MR. GRINNELL: I will have the circular here.

WITNESS: I have one.

Q Have you got a copy of it in your pocket?

A I have.

Q That was the circular that you have reference to? (indicating) which called your attention to that meeting?

A One similar to this.

Q Exactly similar?

A I won’t say as to the German part. The English part is exactly the same.

Q You need not read from it at present. What time was you attention called to that circular?

A That I could not say, as to what hour; sometime during the day, on May 4th.

Q Pursuant to it you had the companies rendezvous–

MR. BLACK: I object to that.

MR. GRINNELL: (Q) What did you do?

A After consultations with the Superintendent of Police he asked me–

Objected to.

WITNESS (continuing) I went and saw the Mayor on the afternoon of May 4th, and His H-nr, the Mayor, and myself had talked the matter over, as to what would be the most advisable

This is important because the Mayor had already determined that the gathering was peaceful. It was later concluded by Governor Altgeld that Bonfield had acted of his own accord in confronting the speakers. (See Pardon document for a particularly damning list of Bonfield’s transgressions).

From Mayor Harrison’s testimony:

THE WITNESS: I went back to the station and stated to Bonfield that I thought the speeches were about to be over; that nothing had occurred yet, or looked likely to occur to require interference, and I thought he had better issue orders to his reserves at that other stations to go home. He replied to me that he had learned the same and reached that conclusion from persons coming and going—he had men out all the time—and had already issued the order; that he thought it would be best to retain the men that were in the station until the meeting broke up, and then referred to a rumor that he had heard that night that would make it necessary for him, he thought, to keep his men there, which I concurred in.

Back to the confrontation.

Bonfield approached the wagon and ordered the crowd to disperse, saying, “I command you in the name of the people of the State of Illinois to immediately and peaceably disperse.” As the speakers were climbing down from the wagon and protesting that they were peaceable, a bomb was thrown into the ranks of the police, instantly killing officer Matthias Degan. The police then began firing into the crowd. It’s not known how many, if any at all, embers of the crowd were armed and might have fired back, but it was later concluded that all police deaths, besides Officer Degan’s, were a result of indiscriminate police firing. It’s not known to this day who threw the bomb, though several conclusions have been made, including the possibility that it was someone from outside the striker’s members, with the desire to escalate the situation.

Over the next several days police swept the city beating and arresting anyone even peripherally involved with the strike movement. Among them Spies, Parsons, and the rest of the eventual defendants.

The Trial

This is getting long, so I’ll say again that it’s important to read the transcripts of the trial to see just how rigged and prejudiced that it was. It’s also important to read Governor Altgeld’s pardon because he meticulously laid out reasons and detailed each instance of the misconduct of the prosecutor, the judge, the jury, the police, and how the jury was chosen. Needless to say, the jury was comprised mostly of business owners. Hand picked by a foreman who was specifically chosen by the judge to make sure that there was a conviction. The judge, Joseph E. Gary, and the prosecutor, Julius Grinnell, thwarted all the efforts of the attorney for the defense, William Perkins Black, to get a fair trial for the defendents. Governor Altgeld had much to say about the judge and the trial in his pardon. It’s astounding to read the pardon, considering the age that it was written in. It’s clarity, indignity, and courage, at a time when to go against the prevailing sentiments of the powerful and rich, and his political enemies, meant the end of his career, is inspiring. I don’t mean to make a hero of Altgeld. He had his social and political faults. But in this instance, his acts need recognition.

A cartoon of Altgeld after the pardons

All the defendants, save for Neebe, were sentenced to death by hanging. Lingg, as I said earlier, committed suicide the day before he was to be hanged. Between the time of the convictions and the hangings there was a great outcry all across the country and around the world really, for mercy and clemency. To no avail. After exhausting all appeals, Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engel were executed in Cook County Jail at 11:57 am, on November 11th, 1887. The Governor at the time, RJ Ogelsby, after considering the continued outrage and cries for clemency, commuted the sentences of Schwab and Fielden to life in prison at Joliet Penitentiary.

The struggle for the 8 hour work day and the struggle for worker’s rights in general were dealt a terrible blow by these events. Though it wasn’t a fatal blow. The Haymarket Tragedy is now considered the source of International observance of May Day (Labor Day). Parson’s wife, Lucy Parsons, went on to become a mighty force and tireless and defiant voice for the plight of American and foreign workers. Her’s is a story in need of a series of diaries devoted just to her.

Again from Chicago History.o r g:

An Elusive Consensus

It still remains difficult, however, to reach a consensus on the meaning of Haymarket. Various attempts to erect a significant monument or memorial in the area of the meeting have never been realized, probably because Haymarket, in spite of the passage of time, remains so controversial and defies any attempt to offer an interpretation acceptable to all interested parties. On March 25, 1992, the City Council finally adopted an ordinance conferring landmark status on the block of Desplaines Street between Randolph and Lake. So far this has only resulted in the placement of a small plaque in the sidewalk near where the speakers’ wagon was located in 1886.

An irony surrounding more recent protests of commemorations of Haymarket in this country is the criticism they have received from the radical left, even though such commemorations are now almost invariably prolabor occasions. One of the most recent scenes in the dramas of Haymarket was the ceremony on May 3, 1998, marking the designation of the Waldheim monument site as a National Historic Landmark. Landmark status had been approved in 1997, and the plaque placed near the monument explained that it “represents the labor movement’s struggle for workers’ rights.” Once again the speakers were dominated by labor leaders, with the keynote address given by the president of the Chicago Federation of Labor, who criticized the latest instances of what he termed corporate greed and disregard for the welfare of workers. Present also were descendants of the martyrs, a representative of the National Park Service, the combined German-American Chorus of Chicago, and the German consul.

But when actress Alma Washington, dressed as Lucy Parsons, unveiled the plaque, self-declared anarchists created a brief disturbance when they spat on the brass tablet and berated the crowd for permitting the Haymarket defendants to be “honored” by the very government that martyred them. By this time many union representatives and their rank-and-file, while still deeply concerned about the attempts by American business interests to weaken the position of the worker, were also likely to take a fairly conservative stand on issues of law and order and police authority.

Other echoes and ironies of Haymarket persist. In late November and early December of 1999, a group of young anarchists severely disrupted the World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle and caused considerable destruction, though they claimed that any property they damaged was only that of large multinational corporations. Around the same time a great-grandson of Peter Butterly, one of the policemen who marched on the labor rally in the Haymarket, was elected president of the Chicago Police Sergeants Association, a young union that had only recently won the legal right to exist. All this indicates how rich and complex a drama Haymarket continues to be, and that the last act will never be written.

Even to this day there is division between unions and police in Chicago. The recent efforts to name a park in Chicago in honor of Lucy Parsons, were opposed by the police, despite the passage of over 100 years time. The Monument to the Haymarket police, originally erected in the Haymarket Square, has had to be moved several times after twice being bombed, and defaced many times. It was finally moved to the Police Academy to keep it safe.

The link for the Police Monument above is wrong. It’s a photo of the most recent monument to the Martyrs, at the site of the bombing. This photo is of the original Police Monument.

The link for the Police Monument above is wrong. It’s a photo of the most recent monument to the Martyrs, at the site of the bombing. This photo is of the original Police Monument.

The Haymarket Martyrs Monument, erected in Chicago’s Waldheim Cemetery ,

remains a sacred place to workers, anarchists, and socialists worldwide. So much so that many other important figures of the labor movement, including Emma Goldman and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn chose to be buried there, alongside those that they consider the heros of working people everywhere. The cemetery is appropriately called “Dissenter’s Row”. I like that name and it’s relevance to the plight of today’s American workers who see the fruits of their labor dwindling, finding it harder and harder to make ends meet, as protections are stripped away, corporations regularly lay off thousands of workers from jobs that were traditionally the strength of American industry, or see their pensions taken away by companies claiming bankruptcy with the compliance of the courts and the government. History has a way of sweeping back around and long forgotten struggles and beliefs once again become relevant to ordinary people, struggling to raise their families in an increasingly hostile work and wage environment. It’s imperative to remember the sacrifices made by these courageous people as we ponder our own futures and what we can do to brighten them.

Peace

Video of Howard Zinn, with his introduction to author James Green’s book, Death in the Haymarket. Zinn starts off slowly, but if you’re patient it is really interesting. Also, I found that the broadband link works best.

Chicago Historical Society’s Haymarket Digital Collection

Chicago History.org’s The Dramas of Haymarket

Working Together Part I

Working Together Part II

Working Together Part III

Working Together Part IV

NOTE

Please feel free to point out any inaccuracies, as I’ve found a lot of conflicting versions of these events.

I posted this tonight because I need to leave the house early tomorrow. I probably won’t be back till evening, when I can reply to any comments. There is so much that is intergal to this story that I had to leave out because it was getting long. Hopefully the links, especially the Haymarket Digital Collection will be read and any blanks filled in.

Peace

super, powerful and disturbing. The workers (people), united, will never be defeated…

Yes, it is. United…a lesson that’s been forgotten in today’s America.

super job, super!

Haymarket & its aftermath, along with Taft-Hartley, pretty much set the seal on the limits of just how effective organized labor would be allowed to be in this country.

in gestation: Constellations

Thanks!

Where do you think it began to turn? I remember when Reagan fired the Flight Controllers. I think that when a President becomes a union buster, then it’s very difficult to overcome that.

I’d still go back to the passage of Taft-Hartley.

You’re correct that the 80’s saw the beginning of the reversals of what gains had been made, w/Reagan & the flight controllers as symbol.

and thought-out diary and another fine addition to this series. It’s so satisfying to see so much purposeful labor creating so much powerful knowledge for BTers.

Thank you Andi.

I actually got myself a little lost in all the information I found. The diary could have been three times as long really. So many pertinent and pivotal smaller events, happening within the larger event.

Thanks Supersoling!

This complex story has been an important element in my thinking ever since I heard it — which was only a few years ago. I actually came across it while doing research on sculptors in Waldheim Cemetery.

There is so much to learn from this story: the need for valor and action, the horror and infutility of violence, the need for politicians willing to risk thier careers in the face of injustice, and, as you so eloquently stated, the circular reoccurence of oppression against workers, immigrants, poor people.

Thanks for telling this incident — with so many of its details and ramifications to the BT community.

No…Thank you :O)

I knew a little about the story from my own reading. I learned nothing about this that I can recall in school. So much of our history is deliberately ignored, and it seems that in most cases it’s at the expense of the weak, the common person. We’re taught propaganda from day one. It’s called Nationalism.

Wow! Our Supersoling is such a hard-working man. This is an amazing story, so well told. Thank you very much, I feel so much smarter now.

Thank you Alice :o)

I wondered if the back to front and front to back and back to the back (!!) way I set it out would work. I guess it did!

ps I really do like horses ;o)

Thank you, Supersoling, for the research on this — it’s one of the most fascinating (at least to me) bits of American history I didn’t learn much about at school. Anyone who was required (as I was) to read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle sometimes finds it hard to even imagine the conditions under which people were forced to survive in those days… and what sacrifices were made by those daring to challenge the system.

On the base of the Haymarket Memorial is a quote from August Spies, (IIRC), his last words before he was executed:

Talk about a fascinating (and still controversial, even after all these years) historical subject for a TV mini-series….

(Great diary series!)

Thank you Janet T.

After I posted the diary I realized I left out one of the most important parts. Thanks for pointing it out! But then, there’s so much that’s embedded within this story that ten diaries might not be enough to properly tell it :o)

Here’s a link to the speeches given by the condemned men.

Just one clarification: within the last year or so, a sculpture has been erected on the site of the Haymarket Tragedy. Mary Brogger’s design of speakers on a wagon is very stark and muscular. It took years of negotiations to come up with something that would satisfy the unions but not offend the police. You can see a picture of it here.

I used to live a few blocks from the site and attended the dedication of the monument. It was a very moving experience.

I (tried to) updated the diary with the proper photo of the Police Monument. Thanks Kahli :o)

My html skills suck though.

Offend the Police huh? They have no ground to stand on once you read the trial transcript and the pardon. Bonfield’s actions in particular, are just insane, even considering the time. Does it justify someone throwing a bomb at them? Maybe, if you’ve been a victim of his brutality.

I HATE HTML. At least you’ve figured out how to get pictures in it which is something I haven’t mastered yet!

Thank you, SS!

You’re welcome, Damnit! ;o)

You have done a great job with this.

Thank you Leezy :o)

It’s a lot to pour over, if you hit some of the links.

btw, how’s that GrandLeezy doin’ ? :o)

Thanks for asking Super. She’s great. We got her up and loving wakeboarding last weekend. What a blast. I got out there too for a bit. Man, I am still sore…lol!She is a blast to hang out with. SHe has this wicked little sense of humor. Cannot imagine where she might have gotten that from.

Hope all is well with you my friend on your side of the country.

Wonderful job, dearheart.

It can be pretty daunting researching these parts of our history, there is so much contradictory information out there. You did a fine job!

At the risk of being naging and redundant, let me say once again: The 8 hour work day, the 5 day work week, the pensions (if any), the overtime, the sick days, the holidays, the vacation days, the lunch break, the restroom breaks, and labor laws meant to protect workers’safety are ALL DUE TO THE WORK AND EFFORTS OF UNIONS and their courageous members. People died, people were severly injured, people were jailed, people lost their jobs, their homes and sometimes their families in order that WE can have all of these things (in whatever measure)we very much take for granted or think somehow the companies and corporations “gave” the workers from the kindness of their hearts.

So know how deeply it offends me when people think it is clever and right thinking to dis the Unions. Have they made mistakes? Yes. Have they sometimes gone overboard? Yes. Have some of them been corrupt at the top ranks over the years? Yes. But did they and do they stand for the disempowered, the poor, the enslaved, the common honest worker, giving them a voice? YES! Do we owe them gratitude and support for almost all of the things that have to do with working conditions, and what we consider the expected (all the things mentioned above)? ABSOLUTELY!

Very good job, SS!

Hugs

Shirl

Tell it, sister!

I’m glad so many people here agreed to participate in this project. It is not surprising (though it is infuriating) that people disrespect unions. Most everyone has heard about the bad behavior some unionists have engaged in. The stories about the bravery, tenacity, humanity go largely untold.

It is the truth, isn’t it. I know I grew up hearing nothing but bad about unions. 99.999% of which was untrue.

When is the last part of this series? You know I have a lot more to say about my long time association with Unions and my many jobs held as a Union Representative.

September 11th is the last scheduled diary.

You’re so right shirl, this is another one of those criminal oversights(no doubt intentionally)in our history books and what we learn, are taught in school…or not taught as seems to be the case in so much of our history.

Truly what I remember being taught is that the government saw how badly workers were treated and passed laws(our of the goodness of their hearts no doubt)to alleviate this injustice when nothing could be farther from the truth.

The union/workers movement was a huge huge part of history and a hard fought and bloody one over many many years with not just men involved but so many women also-another part of regulating women to the back of the bus so to speak.

And you are so right also about many people thinking unions heyday are over, that they achieved what they needed to achieve yet more than ever given the decline of wages and decent working conditions unions again should be more relevant than ever. We(all working people)badly need a huge resurgence of unions to get back workers rights and fair wages. And also not blame the decline in wages, decent working conditions on immigrant labor but place the blame where it belongs on the employers-large corporations and small business owners.

I’ve never been in a Union. And I was always given a negative opinion about them by the people I worked in construction with when I was young. The stereotypical smears. Lazy, overpaid, blah, blah, blah.

I did notice a certain air of superiority with some union workers. Not saying though that that was the norm.

Wonderful job super(as are all these diaries)..especially since this is such a big subject with so many offshoots to to link up to and read about to try and get the whole picture.

This is one of the best series here, after all what is more important than all the working people-who make up this country and make it what it is-the CEO’s wouldn’t have their big pay and profits if not for all the people working who make it possible for them to rip off from the top their increasing obscene ‘wages’. You’d think they’d show just a smidgeon of respect to the workers-yeah a pipe dream I know and something that is apparently never going to change. It’s not even good business to screw over the people who work for them, another thing employers will never seem to learn.

Thank you :o)

Most soft and squishy CEO’s would get a blister just looking at a hammer. That pretty much sums up my opinion of them.

Workers though? They’re the backbone of this country and the powerful have always trampled on them. They’re doing it again, right now. The whole culture is becoming soft, as I see it. The most valuable thing that my Father ever taught me was to give a good effort at my work. That it would make me proud of myself. He was right.

If I could have two things written on my tombstone, it would be these,

He was a good Father

and a hard worker.

I’ll take weathered hands over soft ones any day :o)

Thank you so very much for writing this astoundingly excellent and informative diary.

All I can think of to say is to repeat some inspired platitudes:

1)If we do not know our history, we are doomed (DOOMED, I say) to repeat it.

2)Workers Unite!

Thanks.

I didn’t mean to miss making a reply to you Blueneck.

No offence taken Super, it wasn’t much of a comment, as most of what I wanted to say has been said, and it is hard to add much more than kudos to you for such a thorough diary. I just wanted to leave a small mark to show my support for this diary in particular and for the whole series, too. All of the diaries have been great, and the topic is extremely important right now.

and double wow! There has been so much great information in these diaries (and this one is a grand slam) that we really should be x-posting these at other lefty sites.

P.S. – I am not volunteering

Thanks Teach ;o)

I think we should burn these to disks and pass them out at the schools!

For you :o)

you ol’apple polisher. I give this diary an A+.

I wouldn’t give the kiddies a disc, I’d put all of these diaries on a My Space page.

A late, but grateful thanks for your great work on this diary. I’ve been out fund raising and politickin’ for the last couple of days and was too pooped to comment until tonight;-)