The day is done, bellies are bloated, and now, rather than pretend to give thanks, we can reflect. Might we mourn our motives, the message, and the myths of Thanksgiving Day?

We are not vanishing. We are not conquered. We are as strong as ever.”

~ United American Indians of New England.

As a child, I felt as my Mom did in her earliest years, “What are we giving thanks for on this holiday, hurting a loving native nation?” In the first grade, she was sent to the principal’s office for questioning the “accepted” truth of Thanksgiving. She understood the tales taught to schoolchildren; however, my Mom contrasted these with what she knew of the Indian people. In my youngest years, I could or would not tolerate “Cowboy and Indian” games or the genre in films. I saw the slaughter of a loving people and wondered, as I do now, “Why do we allow this to happen?” Why would we celebrate such carnage?

As a child, I felt as my Mom did in her earliest years, “What are we giving thanks for on this holiday, hurting a loving native nation?” In the first grade, she was sent to the principal’s office for questioning the “accepted” truth of Thanksgiving. She understood the tales taught to schoolchildren; however, my Mom contrasted these with what she knew of the Indian people. In my youngest years, I could or would not tolerate “Cowboy and Indian” games or the genre in films. I saw the slaughter of a loving people and wondered, as I do now, “Why do we allow this to happen?” Why would we celebrate such carnage?

I have yet to understand why we as a nation give thanks on this day. Are we grateful for our ability to rape a land, to ravage a race, or to reject the rights of those that lived in North America before “we” did? I know not. I understand that for the United American Indians of New England, this is a National Day of Mourning.

Our forefathers landed on the shores of what is now the “United States.” Many came to this continent in search of religious freedom others in search of wealth still others to simply make a new start in life. Those fleeing religious persecution then proceeded to persecute others. Those seeking wealth ignored the natives’ stole their land and oppressed them and the life changers road along in the domination and exploitation. We, as a people, as a nation, now celebrate these acts.

As children, we are taught to commemorate the Pilgrims landing. We are told that the natives befriended the white people. They did, both native and Anglo accounts support this belief. Showing compassion for others is consistent with the native culture. The white man saw this open caring nature as an opening, an opportunity to steal, pilfer, and enslave the inhabitants of this, a beautiful land. The pure and principled Puritans saw the strength of sharing as a weakness. They chose to betray, deceive, and diminish the value of the darker skinned inhabitants of the new world.

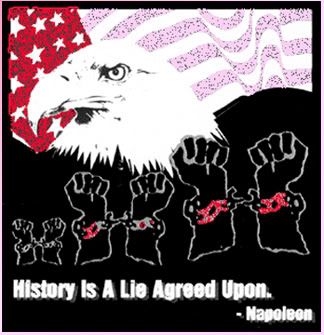

Today, as we celebrate, some say they are not forgetting our past, the founding of this nation; they are remembering. However, it is likely that they only recall childhood chants, the musings of men and women that prefer to hide the truth. After all, who writes the history books the majority of us read? It is the magnanimous man or woman wearing white skin.

Anglos and Europeans wish to appear benevolent; yet, an alternative history tells us a different tale.

The pilgrims [who did not even call themselves pilgrims] did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod — before they even made it to Plymouth — was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians’ winter provisions as they were able to carry.

Nevertheless, on this fourth Thursday in November myths move the nation; and we, as citizenry continue to believe the best of ourselves and our ancestors. We wish to think our forefathers honorable.

Yet, do we? Are we only paying lip service to this history, real or imagined? Is Thanksgiving, in modern times, more than a meal, families coming together to eat, drink, and be jovial? Is it merely an introduction to the holiday season, perchance shopping is our focus and the reason we give gratitude? How often do people truly thank each other, or their ancestors? Perchance, if thanks were to be specified it would be for our shared prowess, and the American ability to possess land that was never theirs to take.

Citizens of these United States rarely discuss this truth. What we as a nation are thankful for is what Christopher Columbus perceived and spoke of succinctly.

Native Americans in the Caribbean greeted their 1492 European invaders with warm hospitality. They were so innocent that Genoan Cristoforo Colombo wrote in his log, “They willingly traded everything they owned . . . They do not bear arms . . . They would make fine servants . . . They could easily be made Christians . . . With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

We, the white man, can force people, human beings into submission. We can come, and conquer. White wonders can enslave these harmless hearts. Converting them to our religion is possible, probable, and oh, what power we can over these naïve natives. I wonder; will we be honest with our neighbors, our image, or ourselves. Will we say that what we honor and give thanks for the bounty of land and wealth we systematically took from the benevolent Indians!

While the whites tell their stories, and hope that no one will ever know or question their facts, their fiction, the “Indians” share theirs. The narrative is passed down from one native born generation to the next. There is ample evidence, even in current day society to verify the veracity of Indian legends. They did everything to welcome and share with us, the whites, and we did everything to destroy, to dominate them. Nevertheless, the [drum] beat goes on. Americans prefer pretence, symbolism, and shopping. Shhh, say nothing, it is a secret, for it is sacrilegious to think that citizens of this country care more for Capitalism than meaningful traditions. However, they do.

The reality never dies. The reality is that on this “Thanksgiving Day,” many mourn. Officially, since 1970, Thanksgiving Day is considered a National Day of Mourning among the Indian nations. Even some educators are observing this, or at least instructing their students on the possibility.

Teacher Bill Morgan walks into his third-grade class wearing a black Pilgrim hat made of construction paper and begins snatching up pencils, backpacks and glue sticks from his pupils. He tells them the items now belong to him because he “discovered” them.

The reaction is exactly what Morgan expects: The kids get angry and want their things back.

Morgan is among elementary school teachers who have ditched the traditional Thanksgiving lesson, in which children dress up like Indians and Pilgrims and act out a romanticized version of their first meetings.

He has replaced it with a more realistic look at the complex relationship between Indians and white settlers.

Complex it is. Originally, there was no sin. Ooops, those words were taken from another text. The earliest settlers were pure; after all, they were Puritans. At least, most of us learned that fable.

There are other versions of this fairy tale. Aspects of these may be accurate. I believe they are, for they appear in each accounting. Hospitality and generosity are among the traditional teachings in tribal communities. Among the Indian populations, the memory lingers; it is passed down from generation to generation. The Indian ancestors participated in a series of feasts throughout the year. The Wampanoag feast, called Nikkomosachmiawene, or Grand Sachem’s Council Feast was among these. It was during this celebration in 1621 that the Wampanoag’s amassed food to help the ill-prepared Pilgrims. The new arrivals were homeless, seeking shelter, sanctuary, and shelter. They had none; they had nothing. These Anglos only had needs and desires.

Conquest and a quest for personal freedoms were their focus; nevertheless, it mattered not that in acquiring their yearnings the Anglos and Europeans robbed the native born of their own liberties. However, I digress. I meant to mention the first Thanksgiving and how it evolved.

This Wampanoag feast is marked by traditional food and games, telling of stories and legends, sacred ceremonies and councils on the affairs of the nation. Massasoit [the leader of the Wampanoag’s] came with 90 Wampanoag men and brought five deer, fish, all the food, and Wampanoag cooks.

The tribal ritual, over time, and with the luxury of legend, became known as Thanksgiving Day. When we celebrate and commemorate this coming together, supposedly we are acknowledging the delight of genuine sharing. Yet, in fact, we are unabashedly praising that we the Anglos and Europeans were intent on becoming occupiers, overseers, and eventually, the oppressors!

When we party hearty, we deny that five years earlier, English explorers arrived hoping to seize land from the native people. These journeymen landed on the shores at a Pawtnxet village. Captain Thomas Hunt was among these early arrivals.

He started trading with the Native people in 1614. He captured 20 Pawtuxcts and seven Naugassets, selling them as slaves in Spain. Many other European expeditions also lured Native people onto ships and then imprisoned and enslaved them.

In 1621, when the white English Puritans encountered the Wampanoag tribes, they identified them as “Indians.” The settlers did not distinguish one culture or clan from another. The Wampanoag were a quiet people. They were farmers and hunters. Their native lands stretched from present day Narragansett Bay to Cape Cod. They, as tradition determined shared their crops and their culture lovingly. They had no expectations, no fear of what was to come. Racism was not their reality. However, with the white man cometh change.

Native lands would eventually become modern day urban neighborhoods. Groves would be demolished; giant buildings would rise from the ground. Tribal leaders and elders would bear no witness and have no say in what was to become of their lands. Governments would dictate codes. President George Washington compared the native born to “wild beasts.” Washington did not wish to provoke their savagery.

Through treaties and commerce, Jefferson hoped to continue to get Native Americans to adopt European agricultural practices, shift to a sedentary way of life, and free up hunting grounds for further white settlement.

Though at times, Jefferson seemed torn; he wished to honor that this land belonged to the natives, the Indians, he also revealed himself, often.

Thomas Jefferson — president #3 and author of the Declaration of Independence, which refers to Indians as the merciless Indian Savages— was known to romanticize Indians and their culture, but that didn’t stop him in 1807 from writing to his secretary of war that in a coming conflict with certain tribes, [W]e shall destroy all of them.

As munificent as past Presidents attempted to be, the more the “man” was able to wield power against the “Indians” the more they wished to exert.

Between 1785 and 1866, over 400 treaties were made with the Indians, and it is fairly well-known that every one of them were broken. Some typical scenarios involved taking back the land promised to them or not allowing the Indians to deal with trespassers themselves the way the treaties promised. Starting around 1985, some Indian tribes, like the Oneida, have won Supreme Court decisions giving them back their aboriginal lands, but because these actions would relocate thousands of white people and involve huge sections of states, the matter of enforcing it is anything but clear. The states have not cooperated, and the Tribes have resorted to suing white residents in the area.

Here is a list of significant events in Native American history:

The Indian Removal Act (1830). This forced a mass relocation of Indian nations to west of the Mississippi, the most infamous one being the “Trail of Tears” which left half of the Cherokee nation dead. Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831). This Supreme Court ruling held that tribes are not foreign nations, but dependencies, and need not be treated equally. Massacre at Sand Creek (1864). Outside of Denver, a wagon train wiped out an entire peace-loving tribe of 200 Indians after inviting them in for supper, then hung their victims’ body parts from the wagons as they traveled westward. The Major Crimes Act (1885). This extended U.S. law enforcement jurisdiction into Indian territories, effectively breaking all treaties that guaranteed they could have responsibility for law enforcement themselves. The General Allotment (or Dawes) Act (1887). This used a “blood quantum” test to take away over 100 million acres of land from “mixed blood” Indians. Massacre at Wounded Knee (1890). U.S. cavalry gunned down 300 Indian men, women, and children for participating in a Ghost Dance, the purpose of which is to enter a world inhabited only by Indians. The Indian Citizenship Act (1924). This conferred U.S. citizenship on all Indians who wanted it and would renounce their claims to tribal identity. The Indian Claims Commission Act (1946). This gave Indians the right to claim monetary compensation for land unjustly taken away from them, in 1865 dollars. The Relocation Act (1956). This qualified Indians for job training if they moved off the reservation to urban areas. The Sioux Occupation of Alcatraz Island (1969-1971). U.S. Marshal’s eventually cleared the Indians off, but they believed they were exercising their rights under an old treaty that gave them first claim to any “unoccupied areas.” The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971). This eliminated indigenous mineral rights in Alaska so the U.S. could build the Alaskan oil pipeline. 25% of all oil reserves, 35% of all coal reserves, and 50% of all uranium deposits still lie under Indian land today. The AIM Occupation/Protest at Wounded Knee (1973). This was a staged protest to expose police brutality, and the crowd succeeded at instigating it. The Fish-ins and Sit-ins at Oregon & Maine (1980s). Indians protested fishing quotas and lumber company activities on sacred ground. The Consumer and Sporting Event Boycotts (1990s). Indians protested use of Indian images and nicknames for products and athletic teams.

Though natives of this northern continent are taking action, they are standing up for their rights, it is obvious. If change might impose on the lives of the lovely fair skinned Anglos or Europeans, then court rulings will remain in limbo. The indeterminate state of affairs will be as the unwritten history, known and ignored.

On this Thanksgiving Day, as on those in the past, gluttony will live long and prosper. The giving of thanks will often be a greedy endeavor. Most Americans will enjoy prosperity, as the natives within this country go forgotten. The original Americans will fret for freedoms lost. They and their numerous and knowing compatriots will mourn, as another year of discrimination passes. I wish them an their offspring authentic peace. I pose no pretense of smoking the pipe.

* While some may say, not all native North American tribes were loving, the Wampanoag practiced peace. I would love to believe that wars on this land were a result of oppressive occupations; however, humans, sadly, can be a little too human for me.

Please Walk a Mile in the Moccasins . . .

Please peruse another wonderful assessment . . .

Betsy L. Angert

BeThink.org or Be-Think