Steve Gimbel for ePluribus Media brings his own wit to bear in his column The Last Laugh as he explains that “humor” is often times the best medicine — even in politics.

Steve Gimbel for ePluribus Media brings his own wit to bear in his column The Last Laugh as he explains that “humor” is often times the best medicine — even in politics.

Forget “Soccer moms,” “NASCAR dads,” and “value voters,” the operative bloc in the midterms were the “comedic constituents.” Stephen Colbert was right to proudly proclaim that every Congressional candidate who appeared on his show “Democrat or Republican, incumbent or challenger” had been elected. The power of the laugh should not be misunderestimated.

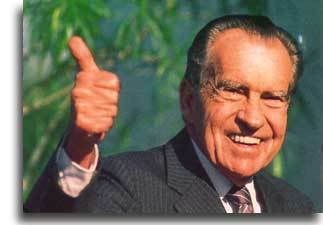

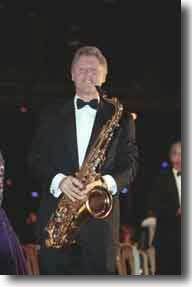

Richard Nixon’s appearance on Rowan and Martin’s Laugh In was the first time major televised comedy was used for political PR and was ultimately as important to his career as the Checkers speech. But the world changed with the Ray-Banned Bill Clinton on Arsenio. The image created the new notion of President as Celebrity-in-Chief.

Clinton’s entertainment connections projected an image of Presidential glamour the country had not seen since Kennedy’s Camelot. His prime time embrace of Aretha Franklin was seen as an act of R.E.S.P.E.C.T. to the African American community as whole, a bump they also got amongst the Jewish population from the first family’s relationship with Barbara Streisand — whose social relevance was in no small part rescued by Michael Myers’ “Coffee Talk” bits on Saturday Night Live.

It was in direct contrast to this that Clinton made the post-prime-time slot a necessary club in the campaign bag. Late Night and The Tonight Show were used to show that candidates had the levitas necessary for high office. “Boxers or briefs?,” a question for Clinton from an MTv candidate forum, is now shorthand for the contentless fluff needed to by to connect with “real people” who cynically distrust anyone with ideas, much less an agenda.

This was the period where the comedic landscape was dominated by Seinfeld. he show was not about nothing; its appeal was its narcissism, its ability to take trivialities, and by embedding them in the intricacies of lived lives, pretend that they were tragedies. To have involved the characters in authentic conflict would have been to kill the schtick — there was never and could never have been “a very special episode of Seinfeld.” It had to be axiomatic that the upper middle-class lifestyle of Jerry, Elaine, George, and Kramer was never in danger, regardless of whether one got served by the Soup Nazi, could dispose of muffin stumps, or celebrated Festivus.

And so it was with us. There were no real threats to our peace and prosperity. Congress could shut down the government and, like George losing his job, nothing changed. It didn’t matter if the President was trying to put gays in the military like a liberal or declaring the end of the era of big government like a conservative. A semen stain on a blue dress could be elevated to the level of a constitutional crisis because we had the luxury of thinking that the most imperative issue confronting us was whether the Commander-in-Chief was master of his domain.

The comedy was sarcastic in its smugness. The worries of post-modern life were mere social constructions. Political theater was “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” Existential crises were, like, so 1960s. And thus turn out for elections, especially among younger voters, approached historic lows.

The election of 2000 featured a brainy, earnest Democratic wonk; a language mangling, ne’er do well Republican; and an anti-telegenic Green repeating hypnotically “there’s no difference between the parties.” And it rang true because there was precious little difference between Clinton’s Dick Morris guided triangulation and the Bob Dole prairie-moderate branch of the GOP.

But Gore and Bush were different — in image. The vicious attacks on Gore came from a general cynicism among the pundocracy. Gore didn’t get the joke. Nothing was at stake and Bush’s playful nicknames and banter with the press showed them that he was in on the gag. We had no worries putting a gentleman’s C student in the White House because the government was too big of a ship to be moved. Its inertia would carry it smoothly regardless of who was at the helm so we might as well spend the next four years with the one we’d prefer to watch Seinfeld with.

“9/11 changed everything,” we were told. Of course, it is not clear exactly what it changed since any change could only be interpreted as a victory for the terrorists. But there was one thing — Letterman was off the air and it was widely declared that “the age of irony was over.” Nihilism had lost its place. We were hated and hunted. Real concerns now replaced self-indulgence.

But irony’s eulogy was also an unapologetically political shot across the bow of the good ship Liberal. By declaring snark to be passé, it clearly argued that this was not a time to embody any progressive traits: cleverness, nuance, or empathy. This was a time to be clear, tough, and burn with anger for revenge. Careful consideration and concern for innocent lives are exactly the sort of namby-pamby softness the terrorists relied on. They hate us for our freedoms and if you dare to use those freedoms, they will hate us even more and kill your children.

Read the rest of Steve’s Column!

About the Author: Steve Gimbel is a philosopher at Gettysburg College. He writes The Philosophers’ Playground and is the editor of Defending Einstein: Hans Reichenbach’s Early Writings on Space, Time, and Motion and The Grateful Dead and Philosophy.

ePluribus Contributors and Fact Checkers: avahome, kfred, cho, JeninRI and roxy

If you like what ePMedia’s been doing with research, reviews and interviews, please consider donating to help with our efforts.

I miss the 60’s………but Steve you brought some forgotten memories back…….. I just never realized!

If Seinfeld is the perfect analogy for the Clinton years, what is the perfect analogy for the Bush years?

I’m going for the European version of The Bachelor.

Have proven that laughter is the best medicine when dealing with truly evil folks. And Olbermann, oh he of the great slap downs in the Edward R. Murrow fashion can also be funny with his “Worst Person in the World!