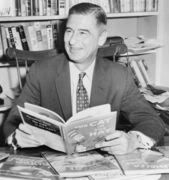

Theodor Seuss Geisel, known to millions as the infamous “Dr. Seuss” of “The Cat in the Hat” fame, had established a degree of fame before the start of World War II, but rocketed to superstardom during and particularly after the end of the war. While generally regarded as “a genuinely idealistic” and good man, he was human — imperfect — and demonstrated one significant moral blind spot in an otherwise wholly commendable life: his utterly racist resentment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It’s important to remember that he was imperfect, and to not gloss over this fact, but it is not the point of this piece. Therefore, I’ve mentioned it early on.

Theodor Seuss Geisel, known to millions as the infamous “Dr. Seuss” of “The Cat in the Hat” fame, had established a degree of fame before the start of World War II, but rocketed to superstardom during and particularly after the end of the war. While generally regarded as “a genuinely idealistic” and good man, he was human — imperfect — and demonstrated one significant moral blind spot in an otherwise wholly commendable life: his utterly racist resentment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It’s important to remember that he was imperfect, and to not gloss over this fact, but it is not the point of this piece. Therefore, I’ve mentioned it early on.

After the jump, however, I’d like to delve a bit into the significance of his other works, and the role they played in the shaping of our national conscience. It’s a role that I believe they can still play in today’s society, perhaps helping to overcome the steady degradation and undermining of our educational system.

The works of Dr. Seuss have found value in the hearts and minds of the young and old. The stories teach important lessons with an air of whimsy and fancy that encourages reading as well as thinking. Not surprisingly, the opportunity to use stories to help inspire the young can be a powerful weapon, just as the control of media outlets and infusion of propaganda can influence the older generations. Fortunately, the majority of Dr. Seuss’s work is timeless — good stories, whimsical and enticing, that give solid lessons in life and even help undermine political hard-liners.

Here’s a list of some of the works written that reflect a form of social commentary, from the Wikipedia page on Dr. Seuss:

Seuss’ children’s books also express his commitment to social justice as he perceived it:

- The Lorax (1971), though told in full-tilt Seussian style, strikes many readers as fundamentally an environmentalist tract. It is the tale of a ruthless and greedy industrialist (the “Once-ler“) who so thoroughly destroys the local environment that he ultimately puts his own company out of business. The book is striking for being told from the viewpoint (generally bitter, self-hating, and remorseful) of the Once-ler himself. In 1989, an effort was made by lumbering interests in Laytonville, California, to have the book banned from local school libraries, on the grounds that it was unfair to the lumber industry.

- The Sneetches (1961) is commonly seen as a satire of racial discrimination.

- The Butter Battle Book (1984) written in Seuss’s old age, is both a parody and denunciation of the nuclear arms race. It was attacked by conservatives as endorsing moral relativism by implying that the difference between the sides in the Cold War were no more than the choice between how to butter one’s bread.

- The Zax can be seen as a parody of all political hardliners.

- Yertle the Turtle (1958) is often interpreted as an allegory of tyranny. It also encourages political activism, suggesting that a single act of resistance by an individual can topple a corrupt system.

- Shortly before the end of the Watergate scandal, Seuss converted one of his famous children’s books into a polemic. “Richard M. Nixon, Will You Please Go Now!” was published in major newspapers through the column of his friend Art Buchwald. Nine days later, Nixon went.

- Seuss’s values also are apparent in the much earlier How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1957), which can be taken (partly) as a polemic against materialism. The Grinch, thinking he can steal Christmas from the Whos by stealing all the Christmas gifts and decorations, attains a kind of enlightenment when the Whos prove him wrong.

- Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose (1948) is often considered to be making a statement about hunting.

- Horton Hears a Who! is said to be a response to the atomic bomb. Also, one of its lines, “A person is a person, no matter how small,” has been used as rhetoric against abortion rights. However, Seuss threatened to sue an anti-abortion group for their use of the phrase. His widow, also strongly pro-choice, has reiterated these criticisms. A lawsuit was filed in Canada in 2001 on this issue.

To this list I would add “Oh! The Places You’ll Go!” as a very important piece for personal encouragement and guidance; I know of at least one friend who read it as part of a drug recovery program. At that time, I’d bought her a copy as a gift for her upcoming birthday, only to have her call me the same day to tell me to go get and read the book. 🙂 The Wiki page notes that it is also a very popular gift for students graduating high school and college — an assertion I can believe, as I’ve gifted it similarly and seen it done likewise.

We’ve seen the efforts of rabid conservative pundits to both push their own propaganda to target children as well as their efforts to rail against any children’s literature that encourage thought, imagination and growth. The most powerful and decisive tools in the battle against ideologies of hate and intolerance are those which will capture the imaginations of the young, feeding the hearts and minds of our children — those with us now, and those yet to come.

The power of the unrestricted imagination, combined with the fullhearted embrace of tolerance and the encouragement of individual thought and achievement, is the most potent “weapon” in any arsenal. Neoconservative and rabid right-wing idealogues are limited here; they will, in time, burn out and devour themselves, but only if they are effectively countered and disarmed. Or, if they win — and take our freedoms, our hearts, our minds and that of our children with them.

My personal recommendations for reading gifts to Republican families this year consist of following tomes:

- The Lorax

- The Sneetches

- The Butter Battle Book

- Yertle the Turtle

- Oh! The Places You’ll Go!

- The Zax

and occassionally a copy of

What’s your (insidiously) suggested reading list for neoconservative Republican children? Why?

Crossposted at: DailyKos, ePluribus Media, Booman Tribune, European Tribune, Never In Our Names, My Left Wing

i own a few of the books and love the inclusive message woven into the pages.

The Wrinkle in Time series is one set that sticks out to me from my childhood. It sparked my interest in the sciences, however briefly. We could use more scientific/critical thinking skills nowadays, imo.

I agree.

The whole of society in the US today is “dummed down” — people want the ‘condensed’ version of the “Reader’s Digest” version. That loses a lot in translation.