Jason Zengerle ruminates in the The New Republic about a very disturbing consequence of the 2014 midterms. With the defeat of Rep. John Barrow of Georgia, there are no longer any white Democrats from the Deep South in the U.S. House of Representatives. We’re excluding Florida here, which I think is justified in this day and age, and if Mary Landrieu loses her runoff election next month, there will no longer be any white Democrats from the Deep South in the U.S. Senate, either.

This is troubling enough, but the problem looks even direr at the state legislative level. To make his point, Zengerle focuses on the fate of a legendary white pro-gun anti-abortion Democratic legislator from Alabama named Roger Bedford:

Bedford, the Birmingham News’s Kyle Whitmire writes, had “the reputation of being bulletproof,” which made him “the Democrat that Republicans throughout the state loved to hate.”

On Tuesday, the Republicans finally got him. Bedford lost by 60 votes—out of more than 35,000 cast—to his GOP opponent. (The race is headed toward an automatic recount, but Bedford doesn’t sound like a guy who thinks he’s going to win.) As recently as four years ago, Bedford was one of 13 white Democrats in the Alabama Senate. After the Republican route in the 2010 elections, that number was slashed to four. Aggressive redistricting by the new Republican supermajority—which made white districts whiter and black districts blacker; and which led to a civil rights lawsuit that will be argued in the U.S. Supreme Court next week—caused two of those four white Democrats not to seek reelection this year. That meant that this past Tuesday, the only two white Democratic Senators on the ballot in Alabama were Bedford and Billy Beasley, the latter of whom represents a majority-black district. Assuming the results hold, Bedford’s defeat means the Alabama Senate has now lost its last white Democrat from a non-majority-minority district.

Or, to put it another way, all eight Democrats in the Alabama Senate now represent majority-black districts, while all 26 Republican Senators represent majority-white districts—and all 26 are themselves white. “The Republicans set out to create districts where no whites would be able to be elected except as Republicans, so it’s so important that you have at least one white Democrat,” Hank Sanders, an African-American Alabama State Senator, told me this week. Bedford’s apparent defeat, Sanders said, “has serious long term and profound racial implications for the state of Alabama.”

There’s no point in sugar-coating this. In the Deep South, the Democratic Party is now the non-white party, and minority politicians don’t have the white partners they need to exercise any but the most local political power. While the problem is less severe in the border states, it has clearly made advances there. You can look at pretty much the whole Scots-Irish migration from the Virginias to Oklahoma and see that the Democrats were trounced last Tuesday. They badly lost Senate elections in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, Mississippi, and Arkansas, and they actually lost two Senate elections each in South Carolina and Oklahoma. Their seat in Virginia was only (just barely) saved by the DC suburbs in the northeastern part of the state.

This isn’t just a problem for the Democratic Party. It’s a big problem for blacks, too.

This situation is so deleterious for African-Americans in the Deep South because, unlike in Congress, where black Democrats have many white Democratic colleagues—not to mention a Democrat in the White House—in these Southern states, black Democratic state legislators (and, by extension, their black constituents) are completely at the mercy of Republican legislative majorities and Republican governors. What’s more, unlike in Washington, where control of the White House—and at least the Senate —swings back and forth between both parties, the Republican control of Southern state houses seems here to stay for a long, long time.

This loss of power is not what progressives or the black community envisioned when the first black president was elected, but the fury of the blowback is now undeniable. Both the party and its African-American base share a self-interest in doing something to combat the impression and (in these parts of the country) the increasing reality that the Democrats are not a party for white people.

This can’t be done by any simple tweaks to the party platform, and there’s a broader cultural element at play here that implicates more than race. Attitudes about religion and human sexuality are also major factors in what has happened, as the country has galloped ahead at breakneck speed to destigmatize homosexuality, for example, while Republican legislatures have furiously sought to restrict women’s rights.

Asking how the party can get white Democrats elected in these regions again isn’t something that blacks or progressive whites are eager to discuss, particularly when the answers may not be to their liking. But their power is at stake, as well as many of the values that they’ve fought for and thought, perhaps erroneously, that they had secured. At stake are basic civil rights (including voting rights), women’s reproductive health, and even the president’s landmark health care law. The black community’s political power is at stake, too, in a major and urgent way.

These problems will require fresh thinking, by which I mean that reconstructing the Blue Dog Coalition is probably not the answer. It’s not the local Chambers of Commerce we need to court, but the economically pressed white voter who must be cleaved from the plutocratic coalition that has enchanted him.

The Third Way led us here. It does not provide the route out of this maze.

about the calls for the Democrats to be more “populist” I always remind myself of some basic realities.

One of the most basic is I see no evidence that a “populist” Democrat can win anywhere below the Mason Dixon line. It is right, in my view, that we highlight economic inequality. But take Georgia. From the exit poll, Nunn did worse among White non-college graduates than she did among college graduates. Identity in the race trumped economic interest. It would be useful to see cross-tabs for vote by age – perhaps younger white voters are less polarized.

It is also true that Nunn hardly ran a “populist” campaign. Maybe the argument can be made that if her approach was more class based these numbers would change.

But there is no escape for Democrats from this that I can see. Certainly I think it makes sense to talk more about class than race, but there is simply no way for a Democrat to avoid race – the republicans will make sure of it.

For 40 years the GOP has used social issues to fight a class way. The Democrats in a mid-term election don’t have an answer yet below the Mason-Dixon line.

As you imply, when the only thing on offer is a choice between bigotry and … Bigotry will win below the Mason-Dixon line and in many other communities above the Mason-Dixon line. And if we’re completely honest, in the past forty years where Blacks have gained political power, far too many have chosen lining their own pockets instead of doing the people’s work. Even the competent and basically decent Jesse Jackson, Jr. got caught up in that.

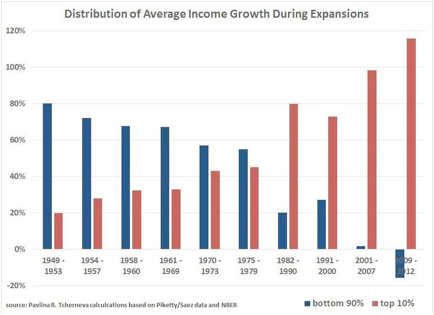

This bar graph (there’s a way to embed it that I haven’t figured out) tells a story that Democrats refuse to acknowledge.

and a couple of graphs. But the real question is WHY? Obama repealed the Bush tax cuts for the rich in 2012. I don’t think the Democrats refuse to acknowledge it – the ones I heard talked about inequality. The exit poll shows a wide consensus that the economic system is unfair – by 65-35.

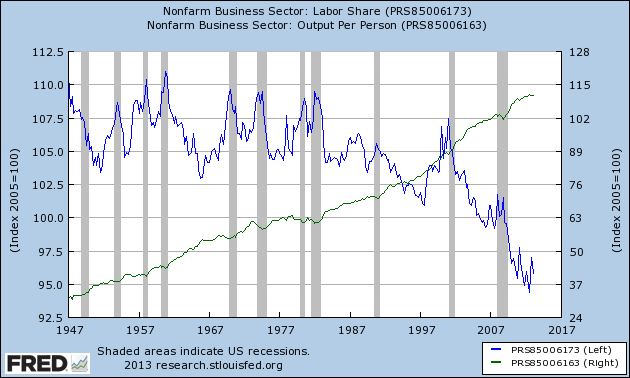

My belief is the core problem is the balance of power between labor and capital has been fundamentally altered. I believe this is because of globalization and automation primarily. Here is one graph that summarizes the issue. Not that the graph changes in 2000 – which is the same time as the trade deal with China. Blue labor’s share of income, the other line is productivity.

But what is the answer?

BTW – here is your graph:

Thanks — just posted the graph in a diary.

Yes — there is consensus that the economic system is unfair. But there’s no consensus as to how it can be made better and who is best to do that.

Most of us carry around some economic frame of reference from the past — the early years of our employment and some from when we were a child (child notions of “good” and “bad” times that later get extrapolated to who had been POTUS at the time).

If Democrats were to turn populist, it would be a different set of candidates. Ms. Points of Light Foundation is not a credible populist.

Also, the Democratic brand has had the DLC stamp for so long and the GOP has framed that neoliberal business-oriented policy as “socialist” so frequently that my own feeling is that the donkey is dead in a lot of sections of the geography.

And populist does not come imposed from a top-down ideology. It must articulate what grassroots people are actually feeling, deal with their fears, and provide a concrete vision that engages them in populist solutions.

That sort of work cannot be done in a single campaign cycle and is really not tactically easy in a campaign, although a campaign can harvest that change in sentiment.

There are huge cognitive problems about politics that must be dealt with in order have honest conversations about principles, policy, and the reality of the world that voters are facing. American voters, thanks to the media, are living in a fastasy world that is going to come up and severely punish them if they do not wake up.

And the GOP is so good with framing arguments and propaganda that that punishment will cause voters to double-down with the GOP rather than seek new solutions to problems.

We are not living in normal political times here. We are living in crisis that is beginning ever so slowly to spiral out of control.

I really don’t buy this, and not only because not 1 person in 100 could tell you what the DLC is. If I look at the exit polling the percentage of people who don’t think Democrats weren’t liberal enough is tiny. Moreover by 54-41 people want the government to do less, not more.

So I went looking for what non-voters think. Pew had the best analysis I can see. They lean Democratic 51-30 – though their attachment to party is much less than voters. They differ in their view of support for the poor – by 51-44 they believe government aid to the poor does more good than harm, while voters think government does more harm by 52-43. But even non-voters are deeply skeptical of government – by 54-43 they think it is always wasteful.

So you can argue that this is because the Dems got tied to Wall Street in the aftermath of the government bailout and this is why the number looks that way. And that is true. But I don’t see a lot of evidence that the populism of Elizabeth Warren, who ran 220,000 votes behind Obama is the answer.

Most of what I read in election results is people simply repeating what they believe. I believe – and have – that most people believe that there is little the government can do to fix the economy. This helplessness is in part driven by a sense that the forces at play – globalization, automation – are beyond the ability of government to address.

Frankly most of the agenda that I have seen suggested as a replacement is pretty weak tea. Voting against the next trade deal is great – but the damage has already been done. Are we for reversing the trade deals? Or I see suggested that we should get rid of the tax incentive to offshore work – but the incentives are small and their repeal would do little if anything to change the balance of power between labor and capital. I read some of the posts in the inequality discussion in the Washington Monthly. A lot of politicians are already saying – and in total it isn’t very impressive as a matter of policy or politics.

I do work on campaigns and have for decades. The notion that there is an obvious solution that the Democrats are intentionally ignoring is frankly wrong. Most politicians will do anything they can to get elected. Simply repeating “If only the Democrats would do this” isn’t going to get very far. Making the argument requires real data and real examples of where things work. In the absence of that much of the talk differs little from sports talk radio.

http://www.people-press.org/2014/10/31/the-party-of-nonvoters-2/

Don’t need to know what the DLC is. If income doesn’t increase when a DEM is the WH, you try the GOP. When that doesn’t work, you try the DEM again.

What I am saying is that in too many parts of the country, the D next to a candidates name has become toxic. And that the establishment actions in DC to avoid substantial action have created the economy that allows voters the illusion that government doesn’t work even when it does. Voters don’t have to be conscious of the DLC connection for the policy choices to hurt them and then blame Democrats.

Take healthcare. People benefiting from Obamacare in places without Medicare extension go from not being able to see a doctor to paying $15 to $75 in co-pays, being balanced billed for charges that the government allows, and not getting full coverage until after they have spent several hundred out of pocket. How does that help them see a doctor more easily? If you look at the map, a lot of people in the Appalachian area have not signed up—even for KYnect. There might be a reason for that. And that reason might go beyond hating Obama.

Look at the policies that Democrats actually moved through Congress for the past 20 years. NAFTA, repeal of Glass-Stegall, RomneycareUSA,…all neoliberal policies and NAFTA was whipped by AL From. How many of them have turned out to be exactly the wrong policy? But queued up are TPP and TTIF that are intended to provide the international legal foundation for transnational corporate sovereignty. Republican attacks on the “socialist” Democratic Party have obscured its neoliberalism from the voters. Voters have been fed so much misinformation and disinformation over the past two decades that they are for the most party clueless. And Guardian US and Al Jazeera America are not really going to provide an antidote to that. DirectTV is suing Al Jazeera America for violating CurrentTV’s contract and providing too much hard news.

The question of whether the Democrats are “liberal enough” is meaningless outside of specific policy details.

I am talking about the fact that the assumptions of socialist/liberal and the reality of neoliberal/business-friendly create cognitive dissonance that ruins the Democratic brand. And the no-issues 2014 election made it only about brand.

Had the Republicans not succeed in disenfranchising enough people, they would have brand problems too. Their problem is different. People hate what they stand for; their candidates with media complicity hide who they are.

It’s a political cul-de-sac that the Democrats, thanks to consultants like From rushed right into.

That link, though–thanks!–makes the gross outline of a simple answer very clear; if there were something Democrats could do to bring the nonvoters, two thirds of the population, out: to persuade them that they have a real stake. And whatever it is Elizabeth Warren didn’t do it.

It’s very hard to bring voters out for someone else just because you campaign with them. Unless you have a strategy for running for larger office that requires you get to know those voters.

I didn’t mean to blame Warren, either. I’m sure everything she did made things better than they otherwise would have been, and the way she thinks and the way she expresses it are both really precious resources to the party and the nation. Just to those who say the party could instantly bring out the nonvoters by adopting her ideas–I wish it could be so but I don’t think it’s that simple.

fladem — just read Armando’s presentation on the Christ-Scott voting results. What jumped out at me was the similarity to 2000. Voter suppression in the Panhandle and how the Duval Co. results magically gave GWB exactly what he needed to win. (Duval never complied with the required machine recount — that was to have been done before the whole matter was litigated in the courts.) One report early in the aftermath. Is it possible that they now have electronic votes that make it much easier to “ballot stuff?”

No.

Florida uses paper ballots that are machine read, but easily readable by humans. There is an easy audit trail now. I have worked as part of the legal protection team in Florida for 10 years. The computers are long gone.

Voter suppression is more complicated than that, and frankly less important that most think.

So, magically Duval Co. Republicans/conservatives were energized enough and in just the right numbers to show up and vote for Scott. Unlike the rest of the voters in the state that participated at a rate similar to 2010 but more favored Christ than Scott this time around.

If Duval Co. hadn’t been so rotten in the 2000 election (and I haven’t followed any Fl elections since then), I wouldn’t be so skeptical. But doesn’t matter because nobody is going to audit the results in Duval — and those that run the election there and count the votes know that.

Should add that wrt the 2000 Presidential election — in the dead of night with nobody watching, Duval Co. came up with just the right number of votes to push GWB into the lead.

I think you make many good points, but I actually think somebody like former Montana governor Schweitzer or former Virginia Senator Jim Webb could potentially turn the tide in a substantial way fairly quickly if they had a simple populist message.

Let me use an analogy in an area I know something about: white middle class teachers working with minority students in poor urban settings. Many of these teachers don’t know how to effectively educate these students. And because these teachers know they are utterly failing to do their job, they are angry at the kids who prove this to them every minute of the day, and they may even start seeing their kids as the enemy.

In trying to address this situation I have seen two general approaches. One, not very effective approach is to have teachers stare down their white privilege during some kind of nightmarish professional development day. It’s not hard to see why this doesn’t work: now, in addition to teacher knowing they are failing in their job, they are forced to feel guilty about their white privilege (or to feel guilty about feeling guilty about their white privilege). To make matters worse, the so-called “white privilege” they enjoy does not, by the way, seem to be of any use in educating these “impossible” students and their “impossible” families.

The second approach to the failure of middle class whites in urban settings is to give these teachers some simple but effective teaching techniques so that they can have some actual success with their students. Success then breeds success, and at some point you might even be ready to benefit from a “white privilege” discussion, though I have not seen this to be very effective in pushing teacher practice in the right direction.

Having a black president is very uncomfortable for the South and America as a whole because the racism issue is always on the table, mostly because the GOP puts it there, since Obama has really tried to focus on results rather than specifically addressing “black grievances.” (America will ultimately benefit from this discomfort, but it probably could also benefit from a little respite from “confronting” its racism, and as soon as Obama is softened by a little distance, a halo will begin to form around him.)

Just like white middle class teachers in lower income communities of color, the vast majority of people (in the South and in general) don’t actually WANT to think of themselves as racist. So, if you can create a situation in which

— “my white guy” (e.g. Chief of the fighting Scotts Jim Webb) shows he’s going to take care of me (simple and clear economic populism);

— part of that message lifts me to the moral high ground by being simple and explicit about a “fair and square deal” for all (and yes, that can include the people of color as long as you don’t dwell on it and add confronting my racism to my already impossible list of frustrated endeavors, including clawing my way out of the lower middle class);

— all the while the candidate maintains the strong white man image

then lower and middle class whites may be able to sort of get what they need and see the Democratic party as holding that.

The situation in politics right now is analogous. The GOP and Fox news are engaged in telling poor and middle class whites, “Hey, here you are busting your ass for peanuts, and these SOBs in the Democratic party want to blame you for the suffering of others as if you actually enjoy some kind of white privilege, AND they want to take what little you have and give it to these dark-skinned complainers.” Compared to that option, electing freaks like Joni Ernst, or forgiving sinners who are “just like me” by voting them back into office after they fall very far is a lot more comforting.

If we had a clear message of economic populism fully held by someone like Webb, then people who are cornered by economic struggle could move forward and feel OK about economic populism because the Democratic Party would rescue them from the white privilege guilt trap being peddled almost exclusively by the GOP. The fact that Obama is actually black makes it too easy for the GOP to pretend that Obama wants to shame you and take what little you have, even though this has never been his M.O. at all.

Combine this approach of simple economic populism championed by a white guy with a rebooting of and long-term commitment to the 50-state strategy that Dean started, then maybe that’s something of a path forward. It would be disruptive to the establishment, just as Obama was disruptive to the Clinton DLC establishment, but the time is ripe for this kind of disruption. The problem is finding somebody as talented or nearly as talented as Obama who is a white male! And BTW, a white female will probably not work with this approach right now, since poor white males are also chafing about gender politics.

Jim Webb is 68 years old and he’s not an economic populist. His economic frame of reference is the US military which is structurally socialist but without the limitations of true socialism. That’s why someone like Webb, Ike, and Colin Powell can use language that sounds like populism even though it’s not a political/economic orientation that they personally ascribe to. Better than what the GOP sells? Sure. But it’s very limited. It’s also why DDE had a GOP Congress for only two years (’53-54), lost both the House and Senate in his first midterm and ’58 was a GOP bloodbath, losing 49 House seats and 15(!) Senate seats (and there were only 96 Senators at that time.)

I appreciate the clarifying comments about Webb. But he is one year older than the presumptive nominee Hilary Clinton and by economic populism, I’m not talking about Huey Long stuff. I’m talking about creating jobs through infrastructure spending, raising the minimum wage, tax credits for tuition for college plus even more substantial support and reform so that college costs stop rising, taxing stock options to support a tax cut for the middle class, etc. None of it is so amazing, but it is impossible for the GOP to embrace and way to the left of them, and it isn’t being articulated in a white-man friendly way by the democratic party. Would Jim Webb be against this kind of “fair shake for the middle class” stuff? BTW, he’s just the guy who comes to mind, as an example.

Before leaping to economic recommendations/suggestions, perhaps we should analyze all of the economic dislocations. For example, can any economy thrive when health care consumes 20% of GDP? Why are individual costs for college at public institutions so high? One reason is that we spend a lot more on prisons and administrative elites.

Why are so few high school graduates “job ready?” Ah, no jobs. Why? A college education does two things: 1) depresses EMPOP which lowers the unemployment rate and 2) increases the educational attainment of the employment population. But other than those graduating with specific professional qualifications (doctors, nurses, some STEM), the supply of college graduates has been exceeding such demand by employers and the economy. (The AMA has long been instrumental in holding down the number of new physicians which is why we have a shortage of primary care doctors.) That surplus, particularly from elite colleges and universities, has gone to Wall St. and banks, corporate marketing/lobbying, CIA, State, NSA. No more “George Bailey’s” that knew and served the interests of their communities. What would the economy and population of Northern VA look like today without the explosive growth of the National Security State? What has it produced that’s been of value? AWOL the only time it was challenged on 9/11 (if the official narrative is correct).

I have yet to see how Obama was disruptive to the Clinton DLC strategy (except by winning in 2008 instead of waiting). The loss of Democrats in the South and Midwest has mostly been Blue Dogs and New Democrats, but the gain in the Northeast has not been progressives.

We have a white problem in America. I’m not sure that continuing to pander to whites is a way out of the institutionalized racism that is still in place. The issue the white teacher in black lower-income community school is continuing school segregation and differential allocation of resources that privilege schools in higher income communities. Not to mention the money being syphoned out of public schools with public/private funding initiatives like charter schools and vouchers. And now, the high-stakes testing that forces teaching to the test by administrative decree. Those institutional issues make the teacher’s job that much harder but the teacher is in most locations precluded from trying to deal with those issues by the political pressure to destroy public unions, including teacher unions. (But interestingly no including law enforcement sweetheart unions.)

Likewise, the economic problem is institutional and not something that individuals can solve but the Democratic politicians could have solved when they had sufficient power to do so. Instead they lowballed what was needed and compromised on that.

And now Democrats have little power to change the institutions and Republicans have power to sabotage and destroy the institutions that could change those situations.

What you advocate is a Pyrrhic victory.

True enough wrt schools, but it’s not appropriate to discount culture. Your and my reference points for education were formed in the fifties and sixties when education was valued. (Cruise the 1940 census to see how few years of formal education people of that time had.) Adequate educational resources was all that minority and poor communities needed more of back then. The need and demand was there.

That shifted for a variety of reasons but if not promulgated by corporate America was encouraged. The educated (unless they’ve become rich) and intellectuals are disdained today. No coincidence that religiosity returned on that wave.

Edwards? He was a Southern senator.

There is now only one white Democrat left in Congress in North Carolina, one considered the progressive state in the South–David Price, who has slowly morphed from progressive to New Democrat as his district was gerrymandered to include part of the Fort Bragg area.

The Republicans have a supermajority in the House and a majority in the Senate of the NC Legislature. The governor is a Koch puppet.

And the voter ID law takes effect in 2016.

Welcome to 1895 redux.

And the administration shut down violently the one cross-cultural movement that was raising the consciousness of people about the issues of inequality and social infrastructure and that had manifested itself across the South as well as elsewhere–Occupy Wall Street. Treated like the Bonus Army was treated by Hoover in 1932.

Because Al From doesn’t want any left wing to the Democratic Party nor does he want a democratic wing. And now we know that Barack Obama was selected as a state senator to be groomed as a black DLC Democrat to follow Hillary’s term. But the ambitious young man jumped the line. And so the inside club has been slapping him down from the moment that Joe Lieberman oppesed a large stimulus through RomneycareUSA to the half-hearted midterm campaigning of 2010 and 2014.

Even within the Democratic Party it seems that black politicians are redlined. And certainly in the media; one is never asked if Steven King is an embarrassment, but white progressives and Democratic officials are continually asked about Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

Well, for me Steven Israel is an embarrassment to the Democratic Party because he limited his partisanship to candidates acceptable to a “bipartisan” club.

With a corrupt establishment, they gain their post-political career incomes. The party and the people who faithfully voted for the party, even against their own better judgement, loses both politically and materially.

Exactly how many of the 192,480 precincts voted for Democrats for any office in this election? Some enterprising Poli Sci student should check that out.

Kudos for that analogy.

Kevin Baker’s Barack Hoover Obama is now over five years old, but Democrats/liberals either still don’t get it or are in deep denial.

Wish I’d read it when it came out. That was just stunning, thanks.

Have been posting the link since it was originally published. Usually totally ignored. Occasionally appreciated. iirc a few responses on the order that I was just an Obama hater.

Shouldn’t have wasted my time because believers not only don’t like facts, but when confronted double down on their beliefs. Interesting article at Vanity Fair on the psychic debunker “Amazing Randi.” Didn’t matter how often or well he debunked the fraudster Uri Geller, those that believed Geller increased.

Finally took the time to read it. Must have missed it in tracking the fate of the ACA in 2009. Excellent history and right on target. Harry Truman was in a similar situation and capitulated to some of the worst actors of the moment on national security policy. And the entry into the Korean War was a hugely bad precedent.

In all three cases–Hoover, Truman, Obama–the required actions were very politically risky not to have the allies that FDR had or LBJ had as a safety net. The characterization of Baucus, Conrad, Nelson, and Reid is on target.

Lots of Democrats and liberals do get it, but there are a lot of progressives who don’t explain enough and come off as merely liberals missing their white privilege. And boy-oh do they focus on Obama as if he’s the only and all-powerful actor like FDR seemed to most people.

It was so instructive when it was published in July 2009.

To his credit, Truman did veto Taft-Hartley but the GOP Congress overrode it. And he only had to live with a GOP Congress for two years (47-48), winning back both the House and Senate in ’48 and keeping both through ’52. The Congressional New Dealers struck back in ’54 and didn’t give up their majorities for a long time after that.

Are you referring to the Naomi Wolf “coordinate response” thing? Because that was… sketchy, let’s say.

The shutdown of Occupy Wall Street was indeed managed through the Police Executives Research Foundation (PERF) and regional DHS Fusion Centers (DHS is responsible for federal building security and had a seat at all of those tables). PERF connected the mayors and police chiefs into a connected task force that included FBI and DHS building security. And they operated in concert.

I have not seen Naomi Wolf’s report. There has been a ton of investigative reporting into how that went down. What is striking that black mayors in Atlanta and Philadelphia were among the first to crack down and among the first to use brutal police methods to do so.

And no one has satisfactorily explained what the real threat of the continued present of Occupy Wall Street was in terms of actual health and safety (the ruse used to violate the First Amendment rights of the protest).

I see the same patter of DHS Fusion Center coordination in the way that the police attacks in Ferguson unfolded and the silence of federal officials.

Don’t forget Oakland, CA Mayor Jean Quan (a once upon a time good Democrat and liberal). Unlike most screw-ups, she paid the right price for her incompetence last Tuesday; Oakland Mayor Jean Quan loses re-election bid

The Oakland Police Department is on a federal short-leash for now. When DOJ drops its oversight, no doubt the OPD will be back to its old ways. Its recidivism is notorious.

The economically-pressed white voter is perfectly satisfied to watch somebody else being pressed even harder.

If you want a social democracy in this country, the first precondition is more social democrats.

If you want social democrats, you have to actually believe that the word ‘society’ refers to an actually-existing thing. In that Scots-Irish belt running diagonally from NW Louisiana to NE Pennsylvania, it doesn’t.

I don’t see what choice they Democrats have except to be the everybody party. They don’t have to go out of their way to prove they’re a party for white people in places like New York and California, and they’d be wasting their time if they tried to reach white southerners who vote Republican because they’re bigots.

Besides, the Republicans have at least as big a problem if they’re seen–as they increasingly are–as a party that’s only for white people. We may have to put some faith in the Scots-Irish youth, and hope the the coming generations will be less racist.

But they aren’t. They are recruiting more and more people like Herman Cain, Tim Scott, Mia Love, Marco Rubio and a lot of Hispanic people in Illinois.

The Tea Party may be lily white, but the only color the Wall street Republicans care about is Green (and I don’t mean Eco-friendly).

A statement from Rev. William Barber and the NC NAACP:

I really do wish you would post on other blogs.

you keep on writing posts thinking that I

The shock to me is that you think what these White Southerners are doing is surprising. How is this surprise to you.

The Black man in the White House is the only one who gives a shyt about the White Working Class.

And they wouldn’t vote for him if it meant saving their own throats. They will continue to vote against their own economic interests because they will follow any shiny object that the GOP throws at them.

This is who they are. That you think you’re sharing some bit of news is what’s surprising to me.

This is who they’ve always been.

I feel for my brothers and sisters down South…but, until they register and vote (I’m looking at you, the 400K Black voters not-registered in Georgia)…what can I do?

“The Black man in the White House is the only one who gives a shyt about the White Working Class.”

And he doesn’t either. No one dies.

And you continue to write these pieces trying to walk around the obviousness of the racism that is wrapped all up in the voters South of the Mason-Dixon.

So, keep on with this populist bullshyt.

These are the people, who, for generations, have voted against their economic self-interest, because they were comforted with the fact..

‘ well, at least I’m not a Nigger’.

When Barack Obama was elected President of the United States, that security blanket that they wrapped themselves in, showed itself to be as threadbare as it’s always been.

You believe someone should coddle them.

I say that they’ve been coddled long enough and fuck ’em, they need to face reality.

But, this continued message of somehow Black people should just be quiet, and then maybe White people who vote against their own self-interest, will want to Vote Democrat..

Naw, Son.

I don’t think so.

With all due respect, that same racism exists in the Chicagoland area and down into southern Illinois. It exists in Wisconsin. It is the driving force for the emergency manager laws in Michigan. It exists in parts of Minnesota. Most of Missouri. And now a huge chunk of Iowa. I could go on.

Yes, this. And that reality is just as true south of the Mason-Dixon line as it is north of it.

But it is not a matter of noise or quiet, it is a matter of dismantling the institutions that preserve that racism from the current form or redlining, to police brutality, to job discrimination, the starving of public education, the classroom to prison pipeline, and on and on. The institutional bases of the perception and the reality of white privilege.

The civil rights movement required white allies and elites to change the law. This will too until there is demographic dominance in elections. But then, look how that can also be torn down. Look at Detroit. Look at what Rahm Emanuel has done to Chicago.

Populism is about coalitions with white allies who aren’t bigots and are willing to work to deal with economic issues and issues of elite power that affect everyone. It’s not that black people have to be quiet, it’s that white people who understand the economic and political issue have to join them and bring the noise.

IMO, for the forseeable future, every incumbent in every needs a progressive primary challenger with a consistent populist message (a first pass would be the Moral Movement agenda). And that includes city and county candidates down to the Soil and Water commissioners. And it includes incumbents who are Republicans. (Watching a serious progressive challenger take apart Louis Goehmert in a primary contest would be a delight.)

White identity politics is a hell of a drug.

Here’s the gist of the non-voter position. It isn’t about ideology.

And in a lot of ways, non-voters are right to think that way.

Howard Dean nails it:

Understand that he concluded by backing Hillary for ’16. So, my respect for Dean’s political smarts went way down — perhaps to nothing.

The solution I’m seeing the Democratic party machine put forth is “We can win back working-class white voters with Hillary, particularly white women. The rest of the Obama coalition will come along.”

That’s not an actual solution, of course. It’s the shit sandwich we’re being handed.

But the alternative is obliteration of this country.

White women are never responsible for the women’s gap. They routinely vote with their husbands. Depending upon them is foolish.

Gender gap is difference in the male/female vote within any demographic. For whites it was 10% in 2000 and 7% in 2004, 6% in 2008 and 7% in 2012. A majority of unmarried white men and women supported Obama in 2008 and the gender gap between the two was only 2%. Maybe we should ban marriage.

I posted this at my blog.

Over the last couple of years Boo and his gang have exuberantly cheered denunciations of the Republicans as a party of old white men waging war on women.

They have repeatedly denounced the white working class and especially the Scotch-Irish of Appalachia for racism and crowed the Democrats didn’t need them any more, they could dominate the politics of the nation with minorities, elite whites, and the white youth vote.

They have joined the screaming in absolutely ever incident of incendiary and furious, bogus accusation of white cops, white demonstrators, and white people as racist murderers of innocent black youth.

They have urged amnesty and open borders expressly to flood the country with non-whites who will mostly vote Democratic in order to permanent cripple the power and importance of whites in America and the Republican Party, as well.

They have at every opportunity sneered at the Republicans as “the white peoples party” and crowed that the Democrats were the party of minorities.

And they have publicly exulted that the demographic changes in the US that increase the proportion of non-whites will kill off the Republican Party.

They were still exulting just a few short weeks ago.

Then came November 4, 2014.