The Pollster average of polls has just put the Brexit side ahead for the first time, which given the trend those polls have been taking, means we now have to talk about the probability of the Brexit process starting in 10 days time. In To Brexit or not to Brexit: That is the question I examined the ramification of Brexit for the UK, and in A Tale of Two States I looked at the implications for Northern Ireland in particular. In this piece I will embark on a speculative journey envisaging how a post Brexit Europe might evolve.

First of all, I am working off the assumption that the result will be tight, with Scotland and N. Ireland voting to remain in the EU but being swamped by the Brexit vote in England. There is therefore a strong probability that Scottish nationalists will seek a new referendum on Scottish independence in order to remain within the EU, and Sinn Fein will call for a new referendum on a united Ireland to enable N. Ireland to remain within the EU.

Whether either referendum will be carried is open to conjecture, and much will depend on the timing and circumstances of the vote, but there is no doubt that the UK itself will be destabilized as a result. (The position of Wales is more ambiguous with many blaming the EU for the failure to support the Tata steel works in Port Talbot, as if any Tory led Government outside the EU would have done any different…)

Next comes the 2 year exit negotiations provided for by Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. If Wolfgang Schäuble has anything to do with it, it seems that the EU will take a hard line: No preferential access to the single market without a significant financial contribution and the free movement of labour: both factors Brexit was supposed to avoid. Therefore we can expect the re-erection of trade barriers between the UK and the EU.. Regardless of the outcome, the two year negotiation period could result in a lot of uncertainty, volatility and postponement of investment decisions resulting in reduced growth all round, but especially in the UK, even with a much devalued Pound.

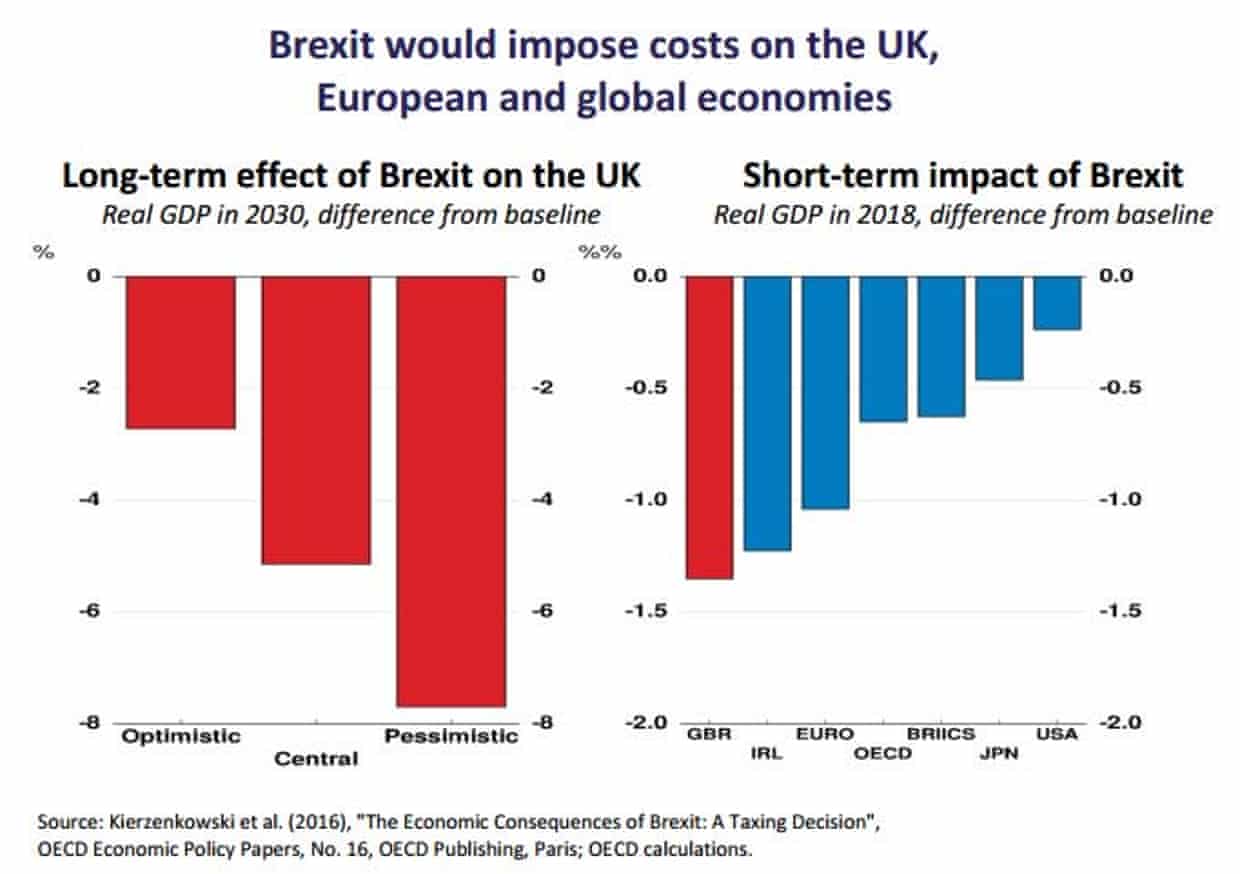

The OECD expects Brexit to send shockwaves through the global economy and expects the UK economy to be some 5% smaller by 2030 than would otherwise have been the case:

The next most heavily impacted economy would be Ireland, with GDP growth expected to be 1.25% less by 2018. A detailed study (PDF) by the ESRI think tank puts the effect on bilateral trade flows at c.20% heavily concentrated on the food and pharmaceutical sectors and estimates that this will be only partially offset by Ireland’s increased attractiveness as a location for FDI with a major competitor for FDI, the UK, no longer in the single market. Any disruption of the single all Ireland electricity market might also require the building of inter-connectors with France to lesson dependency on the UK in a crisis situation. The situation regarding 400,000 Irish born people in the UK and the 230,000 British born people resident in Ireland would also be the cause of some uncertainty and anxiety – but no more so than the estimated 2 million British Expats in France and Spain, many of whom will be voting for Brexit to stop immigration into Britain!

The lie that immigration has depressed workers wages by 10% and that it is immigrants rather than government cutbacks that are responsible for NHS overcrowding will soon be exposed if a significant proportion of these often elderly expats end up returning to Britain post Brexit. The Economist concludes that there are no good trading models for the UK to follow post Brexit, which is why the Brexit side have shifted the debate to the emotional low ground of barring immigrants and blaming them for the pressure on health services – a shift which has provoked a senior defection from the Brexit campaign.

But the EU as a whole would also suffer, with the OECD putting the impact on growth at c. -1% by 2018. So might this not provoke a more pragmatic attitude towards post Brexit negotiations with the UK? My belief is no: Even at some cost to themselves, EU members will unite around the notion of making Brexit as painful for the Brits as possible, as otherwise they would only encourage other nationalist groups in other member states and risk the disintegration of the EU as a whole. It will be a fight for survival at that stage, and anyway, why would Frankfurt or other financial centres continue to allow The City in London easy access to the single market when they could pick up that business for themselves?

Almost alone in opposing this hard line will be Ireland, anxious to maintain previous bilateral deals underpinning deep trading and cultural ties with the UK, and concerned, above all, to prevent the re-erection of border posts on the North-south boarder. Any setting up of border posts would simply be to invite a return of terrorism to the North by nationalists sensitive to any symbols of separation, North and south. This is an issue on which Ireland may and should be willing to use its veto. Maybe some compromise will be found, allowing a tacit back-door trading of UK goods provided they are routed through Ireland, but it is hard to see how there will not be some escalation of trade and migration controls, bureaucracy, delays and costs.

Northern Ireland agriculture will also be hugely disadvantaged relative to the south which will lead to all sorts of smuggling, fraudulent paperwork, and ultimately, a need for even greater subventions from England. But will England wear it, especially if Scotland leaves and the much closer Scots-Irish ties become manifest? I can see a shrinking English Treasury simply dumping Northern Ireland at the first opportunity, leaving it with no ultimate destination or transition plan. A recipe for disaster.

Perhaps the rest of the EU will be galvanised into some kind of concerted action to offset the deflationary impact of Brexit, anxious to head off nationalist movements, and a slide into quasi fascism. A very great change of mentality and leadership would be required. In many ways the UK will be withdrawing just as it has vanquished Europe, having gotten English accepted as the de facto lingua franca, and Anglo American neo-liberal economics and neoconservative politics as the dominant ruling ideologies.

It is difficult to foretell how the absence of the UK will shape EU policy, but a greater willingness to consider state intervention (at an EU level) may be one consequence. We may therefore see re-energised EU regional, structural, and cohesion policies and budgets together with a greater willingness to consider major inter-state infrastructural development projects part funded by the European Investment Bank. We can but hope.

Meanwhile, in England and Wales we will see competitive devaluations of the Pound, rising inflation, a sharpening of the class war to prevent wages following inflation, a deepening of regional and social inequalities as a cash strapped exchequer cuts spending, a lowering of environmental standards, and a reduction in the “red tape” which protects worker’s rights: A right wing bonanza with key business interests much more influential in determining government policy.

Labour may well decline into irrelevance as it loses its Scottish, Welsh and northern English industrial power bases. Attempts will be made to turn the Commonwealth into a “common market” and to gin up the “special relationship” with the USA. Great play will be made of the tiniest advances in foreign relations and England’s role in World affairs “punching above its weight”. No doubt the Queen will be used even more to provide a focus for nationalist sentiment and national unity. Tourists will flock in encouraged by the cheaper Pound.

A tacit competition will take place between the EU and the UK to establish which model of governance will be the more successful. England will flaunt the flexibility of a floating currency, the importance of local democracy, and the abandonment of red tape in promoting growth. But they also won’t have the “Brussels Bureaucracy” to kick around any more in order to deflect attention from their own ruling class and the increasingly sharp divide between the comfortable middle class proud to have “re-taken control from Brussels” and the great unwashed, unemployed on minimal benefits, on zero hour contracts, and relatively declining wages. England will have to find a new war to fight in order to bleed off the young and deflect the masses from blaming their own masters for their plight. No doubt some future US President will create one for them.

The EU as a whole? Not so much. It’s very inchoate size and diversity prevents it moving rapidly in any one direction. The EPP will gradually lose its grip beset by nationalist movement to its right and younger protest parties to its left. More comprehensive trade agreements (short of actual membership) will be negotiated with Turkey, Russia, the Balkan states and major trading partners world wide. Because of the size of the single market, these deals will be much more advantageous than anything the UK will be able to achieve on its own. Negotiations with the US and global corporates will be much more robust than an obsequious UK retaining illusions of empire and anxious to play with the big boys on its own at almost any price.

Some writers even suggest Ireland would be better off re-joining the UK thus re-uniting Ireland and attaining greater representation in Westminster than it ever could in Brussels. This is delusional thinking. It’s not going to happen, whatever the close and cordial relations which currently exist between the two states. Ireland is not going to turn its back on a hard won independence and much closer ties to the rest of the EU.

However the EU needs to be aware than in Ireland, as in the rest of the EU, there is increasing disillusion with the European project and the perceived centralisation of power for the sake of it in Brussels. Some new vision for the EU needs to be found, something more substantial that the elimination of roaming charges or the common availability of emergency healthcare. Unless the EU starts to deliver more concrete benefits, it’s authority and prestige will continue to wane.

My suggestion would be that it needs to start developing common taxation systems, public healthcare, procurement, education, social welfare, pensions, energy, governmental computer systems architectures and consumer protection policies which individual member states can adopt or not at their own pace, but which provide a basis for better and more efficient administration, healthcare, inter-operability and transferability of educational standards, economies of scale and sharing of research. Perhaps one member state can become the lead developer for each area.

Yes this will involve an element of fiscal transfers, but on a basis that is transparent and fair to all. The EU has to start demonstrating that it can be more than the sum of its parts, and that every member state can, in one way or another, become a net beneficiary. It has got to stop being a case of “us and them”, and the departure of the UK, which has consistently refracted its own class tensions onto a European plane will actually facilitate that process. There are actually times when smaller is more beautiful.

Cameron brought it upon himself … emulating the Iron Lady to clinch a royal place in British history. I do hope Cameron and the Tory party will be out as the Brits vote to Leave the European Union. I do see a lot of upsides as the British have been too agressive in the Middle East region and undermining the Russian government. Where did all the stolen billions from the Russian people go and which nation offered shelter to the oligarchs?

NATO had become a tool of right-wing forces of Uncle Sam and the Union Jack. See all speeches and papers from the Atlantic Council since the 1990s. It’s urgently needed to put a break on EU expansion eastwards towards Russia. A Brexit will be useful to once again separate the British Isles from the continent.

I don’t believe the scare mongering from all establishment institutions that brought the financial and banking crisis on the common man. EU HQ in Brussels, IMF and OSCE are by definition biased on the Brexit vote. The global stock exchanges and the British pound are under pressure as the polls indicate an edge towards the Leave vote. Oddly enough, Ladbroke still offer the advantage backing Cameron, his Tory party split in half and Corbyn with Labor.

○ Erstmals in der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik liegt die Rendite der zehnjährigen Staatsanleihen bei null Prozent | Süddeutsche Zeitung |

○ For Russia, Brexit would be an opportunity not a tragedy | The Guardian |

Western diplomats say the issue of Brexit appears to be at best peripheral in Russian official thinking for now, but one place where the issue of the Kremlin’s response to a potential parting of the ways between London and Brussels is very much on people’s minds is Kiev.

“Russia is enjoying the disintegration of Europe; the refugee crisis is in Russia’s interests and Russia is inflaming it,” said Alex Ryabchyn, a Ukrainian MP. He said the British voice inside the EU was vital for keeping pressure on smaller countries to put up a united front against Moscow.

“In France or Germany there are strong pro-Russian camps, and Britain doesn’t have that; Britain has always been a strong voice inside Europe advocating for Ukraine.

○ EU referendum: Is Putin betting on a Brexit? | BBC News |

○ Putin will be rubbing his hands at the prospect of Brexit | Opinion – Guy Verhofstadt |

Of course, NATO is non-political on Europe’s defense strategy vs Putin’s Russia 😉

Both Georgia’s Saaskashvili and former NATO chief Rasmussen have joined the Ukraine gravy train …

“Russia is inflaming it…”??? In what world do those people live?

If the referendum goes in favor of ‘divorce’, Parliament has to agree to it by a vote, I suppose. It is non-binding, so the Parliament must have the last word. It could hardly vote outright to ignore it. How would David Cameron ever handle this? Someone in Britain must have a plan by now. Maybe not, London is probably as clueless as Brussels, where any plan for Brexit seems publicly limited to Wolfgang Schaeble’s warnings of harsh consequences. No where have I seen any mention of the possible immediate political reaction in London. It is hard to image that David Cameron could survive. It is not difficult to imagine that the British political and financial establishment or at least the most powerful sections of it would find a way to circumvent the result: How are we going to get of this shit now? Thanks, Dave.’ I don’t expect such dire economic consequences as predicted now. This seems merely an attempt to frighten Brits from going for Brexit. Once again I predict that the vote will be won by the Remainers. You just have to love the hypocritical rich Brits living in the European mainland voting for Brexit. Has the Empire ever really ended? Three of the G8 countries are Britain and two of its very successful former colonies, USA and Canada (throw in Australia for good measure). That’s obviously how English became the dominant language. Which other language could ever possible have become the lingua franca: German? Even after a theoretical Brexit, all that will not change.

The Remainers will make the voters keep voting til they get it right?

There’s a a longstanding tradition in Europe of redoing referenda until they generate a pro-EU result.

Actually no. Ireland voted twice on the Nice Treaty because first time around it was defeated on a very low turnout because the debate had been hijacked by the anti-abortion lobby insisting it would facilitate abortion – which was, and is, b*llshit. When a protocol was added giving an explicit assurance to this effect it was passed by a 2:1 margin on a far higher turnout. So what’s wrong with that?

Ireland also voted twice on Lisbon; Norway has had two referenda on joining and Denmark two on reducing opt-outs (to be fair, they were both rejected). There were also plans to redo the French referendum on Maastricht, but it squeaked by.

Correct. If we want to be absolutely exhaustive about it, there have been 46 distinct referenda on matters related to the EU since 1973. Many of which were held in countries such as the UK with little or no tradition of holding referenda – so you could argue that the level of democracy and consultation in EU member states has increased with or since accession.

In 39 of these referenda, the side supported by the Government of the day won. That is a pretty high proportion given that governments frequently get turfed out at the next election. There were three defeats for the government of the day which resulted in the Government of the day negotiating changes to the Treaty in question and subsequently carrying a second vote by a much higher margin:

First Defeat and re-run

Referendums related to the European Union – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Second defeat and re-run:

Referendums related to the European Union – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Third defeat and re-run:

Referendums related to the European Union – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Note that in each case there was a much higher turnout for the second vote and the vote was carried by a much higher margin than the original defeat.

I think we can draw a number of conclusions form this:

I would call the above evidence of democracy in action and working. For some reason some “progressives” seem to think the reverse: that the EU is less democratic than it ever was.

In one sense that may be true. Now that the EU has expanded to 28 members its institutions must reflect the views of 28 members which necessarily makes it more remote from the views of any one member. But it would be less democratic, not more, if one member where to be increasingly able to determine the path of the EU as a whole.

The UK campaigned vociferously for the expansion of the EU membership to include 10 eastern European states, and now it complains that the EU is less responsive to its particular concerns. But that is the logical consequence of the expansion!

Reminds me of complaints in the good ole USA when white male property owners lost their exclusivity on the right to vote

OK, so what’s in it for Britain? Or should I say, “what’s in it for Britain’s 1%”?

I think it is better seen as a fight among the 1%.

For the tories, the EU has long been a good target of blame for all Britains woes (in particular those created by said tories), at the same time as the financial elite has enjoyed the market access and the old time elite has enjoyed the money to large landowners from EU’s common agricultural policy (CAP). But having blamed the EU for so long, there is now a significant portion of britts who really believe things would be better on the outside. And there is a faction among the elite who would like to use it to gain more political power at the expense of others in the elite. They might lose money on it, but it is not like they can spend what they already own.

Think of Boris Johnson as the UK’s Donald Trump if you will. But with slightly better hair.

Rather like the US idiots who think a balanced budget would help the economy and there are no jobs because taxes are too high. Since they believe the government should less and have a balanced budget, plus lower taxes, they follow a path that can only lead to zero taxes and zero spending, hence zero government.

I’m not going to comment on all sorts of rumours … witness accounts vary too much … she tried to break up a fight … attacked with knife … moments later two shots were fired .. MP taken to hospital and is in critical condition …

○ Live: MP Jo Cox Critical After Being Shot | Sky News |

○ MP Jo Cox injured following reports of shooting and stabbing in Birstall, West Yorkshire | BBC News |

○ PM Cameron: It’s right that all campaigning

has been stopped after the terrible attack on Jo Cox.

I won’t go ahead with tonight’s rally in Gibraltar.

○ Twitter account Jo Cox MP

○ Jo Cox – biography

So awful

No political motive about the Brexit discussion … a local incident waiting to happen for more than a decade.

○ Thomas Mair a Long Time neo-Nazi of National Alliance

there is an odd synchronicity in events in the UK and the US: some months ago, we were hearing about the election of Jeremy Corbyn at the time that the Sanders campaign was becoming a serious force. Now, the stupid nativist chickens are coming home to roost in both countries…

Frank, you may find this of interest. http://ritholtz.com/2016/06/brexit-the-aftermath/

Thanks

With the Undecideds breaking for Leave this is becoming a disaster for the UK political class. A Brexit almost certainly means another Scottish Independence referendum and this time almost certainly means a Yes majority. It also means the Tories will join Labour in a faction fight exactly at the time the government needs to be focused on the nuts-and-bolts of leaving the EU.

Glad I’m watching this from o’er the Pond.

More bs … hoping the Leave camp wins tomorrow. As I have written, Britain is a key voice inside Europe for NATO aggression. See my earlier posts about the Atlantic Council, a think tank for ambitious neocons seeking a career in US foreign policy. I’m thinking about Yvo Daalder a few years ago: “make Russia a pariah state” ahead of further NATO expansion. Libya and Syria were well planned for turmoil and chaos. Serving ally Israel and the Gulf States by placing hrash sanctions on Iran. Must get rid of the axis Tehran – Baghdad – Damascus – Beirut and global terror of Shia funded by the Ayatollahs.

○ HRC foreign policy advisor Nicholas Burns: Articles for the Atlantic Council

○ Boston College – Nicholas Burns Biography

○ The Insiduous Role of the Atlantic Council: Securing The 21st Century For NATO