When I saw the election results, particularly when I saw the distribution of the vote, I immediately thought of former Virginia Senator Jim Webb. As a kind of self-appointed ambassador to the Scots-Irish hill people diaspora, he’s said some things I thought wrong-headed or even insensitive, but he’s also helped me understand some things from their point of view. I was curious what he’d have to say about President-Elect Donald Trump.

Well, he gave a speech at George Washington University yesterday, and here’s part of what he said.

Hopefully the results of this election will provide us an opportunity to reject a new form of elitism that has pervaded our societal mechanisms. This is not quite like anything that has faced us before in our history. It has many antecedents but the greatest barrier, even to discussing it, has come from how these elites were formed, largely beginning in the Vietnam era, and how their very structure has minimized the ability of the average American even to articulate clearly and to discuss vigorously, the reality that we all can see.

Part of it was the Vietnam war itself, the only war with mass casualties – 58,000 American dead and another 300,000 wounded – where our society’s elites felt morally comfortable in avoiding the draft and excusing themselves from serving. As I wrote of a Harvard educated character in my novel Fields of Fire, “Mark went to Canada. Goodrich went to Vietnam. Everybody else went to grad school.” This created, among our most well-educated and economically advantaged, a premise of entitlement that poured over into issues of economic fairness, and obligations to less-advantaged fellow citizens. Writer and lawyer Ben Stein wrote many years ago of his years at Yale Law School with Bill and Hillary Clinton, “that we were supermen, floating above history and precedent, the natural rulers of the universe. … The law did not apply to us.”

Part of it was the impact of the Immigration Act of 1965, which has dramatically changed the racial and ethnic makeup of the country while keeping in place a set of diversity policies in education and employment that were designed – under the Thirteenth Amendment – to “remove the badges of slavery” for African Americans. This policy designed for African Americans, which I have supported, was gradually expanded to include anyone who did not happen to be white, despite vast cultural and economic differences among whites themselves. More than 60 percent of immigrants from China and India have college degrees, while less than 20 percent of whites from areas such as Appalachia do. But to be white is, in the law and in so much of our misinformed debate, to be specially advantaged – privileged, as the slogan goes, while being a so-called minority is to be somehow disadvantaged.

Frankly, if you were a white family living in Clay County, Kentucky, one of the poorest counties in America, whose poverty rate is above 40 percent and whose population is 94 percent white, wouldn’t this concept kind of tick you off? Wouldn’t you see it as reverse discrimination? And wouldn’t you hope that someone in a position of political influence might also see this, and agree with you?

And part of it, finally, is that diversity programs, coupled with the international focus of our major educational institutions, have created a superstructure, partially global, that on the surface seems to be inclusive but in reality is the reverse of inclusive. Every racial and ethnic group has wildly successful people at the very top, and desperately poor people at the bottom. Using vague labels about race and ethnicity might satisfy the quotas of government programs, but they have very little to do with reality, whether it’s blacks in West Baltimore who have been ignored and left behind, or whites in the hollows of West Virginia. Behind the veneer of diversity masks an interlocking elite that has melded business, media and politics in a way we could never before imagine. Many of these people also hold a false belief that they understand a society with which they have very little contact. And nothing has so clearly shown how wrong they are, than the recent election of Donald Trump.

A decorated Vietnam veteran, Jim Webb has long interpreted most things through the lens of that war. Because I was six when the last American left Saigon and because my father was too old and my older brothers too young to serve there, I don’t share Webb’s experiences of the war on any level. I don’t have a before and after to make comparisons. What I do know it that my oldest brother was born in Germany because my father was sent there after college, and that he was draft eligible by 1974 and therefore had a personal interest in the progress of the Vietnam conflict during his high school years. I had to register with the Selective Service but I never faced the prospect of being compelled by my government to serve in the armed services.

I think more than the war itself, the decision to eliminate the draft created a chasm between our military and our elites. Perhaps during the war there were places like Yale Law School where people felt that they were “floating above history and precedent, the natural rulers of the universe,” but when it came time to make decisions about sending kids to fight in Panama or Kuwait this phenomenon was broader and a much larger segment of society could view the political decisions with a sense of voyeuristic detachment. I was a sophomore in college when Poppy Bush went after Manuel Noriega and I opposed the action because I couldn’t discern the real motivations for it, but it never occurred to me that I might have to participate. The soldiers were not my peers, but more like pieces on a Risk board.

On the other end of this, in the communities where many people still opt for voluntary military service, the experience of being a pawn with no say must have been experienced much more directly. And, yes, that experience began even when the draft was still existent but didn’t apply to college kids and grad students.

I think this sense of powerlessness and separation leads directly to feelings of resentment and anti-elitism. My impression is bolstered by the work of Prof. Kathy Cramer of Wisconsin-Madison who spent nearly a decade talking to rural Wisconsinites in preparation for her book The Politics of Resentment. She spoke to the Washington Post both before and immediately after the election and here is some of what she had to say.

What I was hearing was this general sense of being on the short end of the stick. Rural people felt like they not getting their fair share.

That feeling is primarily composed of three things. First, people felt that they were not getting their fair share of decision-making power. For example, people would say: All the decisions are made in Madison and Milwaukee and nobody’s listening to us. Nobody’s paying attention, nobody’s coming out here and asking us what we think. Decisions are made in the cities, and we have to abide by them.

Second, people would complain that they weren’t getting their fair share of stuff, that they weren’t getting their fair share of public resources. That often came up in perceptions of taxation. People had this sense that all the money is sucked in by Madison, but never spent on places like theirs.

And third, people felt that they weren’t getting respect. They would say: The real kicker is that people in the city don’t understand us. They don’t understand what rural life is like, what’s important to us and what challenges that we’re facing. They think we’re a bunch of redneck racists.

So it’s all three of these things — the power, the money, the respect. People are feeling like they’re not getting their fair share of any of that.

What’s interesting to me is the sense of alienation that feeds racism, yes, but also a broader anti-urban, anti-intellectual sentiment.

What I heard from my conversations is that, in these three elements of resentment — I’m not getting my fair share of power, stuff or respect — there’s race and economics intertwined in each of those ideas.

When people are talking about those people in the city getting an “unfair share,” there’s certainly a racial component to that. But they’re also talking about people like me [a white, female professor]. They’re asking questions like, how often do I teach, what am I doing driving around the state Wisconsin when I’m supposed to be working full time in Madison, like, what kind of a job is that, right?

It’s not just resentment toward people of color. It’s resentment toward elites, city people.

To drive home this point, I thought the following was particularly illuminating:

Thank God I was as naive as I was when I started. If I knew then what I know now about the level of resentment people have toward urban, professional elite women, would I walk into a gas station at 5:30 in the morning and say, “Hi! I’m Kathy from the University of Madison”?

I’d be scared to death after this presidential campaign! But thankfully I wasn’t aware of these views. So what happened to me is that, within three minutes, people knew I was a professor at UW-Madison, and they gave me an earful about the many ways in which that riled them up — and then we kept talking.

What’s important here, I think, is to understand that racism is one part of a bigger set of resentments. People can argue over whether Trumpism is driven primarily by economic insecurity or by racial attitudes but it’s clearly driven by both of those things and also by a more general sense of voicelessness and lack of power and respect.

There’s definitely a component of deservingness involved, which gets to misperceptions about who works hard and who gets the lion’s share of federal assistance. That feeling is fed constantly by Republican messaging. But I think it’s wrong to focus too much on the individual components of this resentment and anti-elitism. Rather, the whole package must be considered.

One thing to remember is that these communities actually do agree with the Democrats’ critique of the Republican Party as an organization that isn’t looking out for them. This is probably the reason that Barack Obama did substantially better with them when running against a guy like Mitt Romney than Clinton did running against a guy like Donald Trump.

I was thinking about all of this when I read Jamelle Bouie’s piece yesterday: There’s No Such Thing as a Good Trump Voter: People voted for a racist who promised racist outcomes. They don’t deserve your empathy.

I liked Bouie’s piece in the sense that it was well-constructed and strongly argued and that it came from a place of moral seriousness. In his demand that people take responsibility and be held accountable for empowering a Trump presidency and all that results from it, I could find little to argue with.

Yet, I think we can do better than denying tens of millions of people any empathy. I don’t think we should ignore that we share a broad dissatisfaction with our elites, and I don’t believe in leaving anyone behind. Most of all, as I’ve been pointing out since the election, the left in this country has to reckon with rural America’s hostility if it’s going to ever have power again in state legislatures and in Congress. So, even if we feel that they’re undeserving, we need to temper that sentiment for reasons of self-interest if nothing else.

Now, Jim Webb has a way of talking about racial preferences that I find frustrating and problematic, but when he says that “blacks in West Baltimore…have been ignored and left behind” no less than “whites in the hollows of West Virginia,” he’s touching on something important. It’s important because it makes it easier to see how electing a champion (however flawed and ridiculous) like Trump is meaningful and validating to his supporters in a way that having the Obama family in the White House was meaningful and validating to blacks in this country. It’s important because it reinforces the point that our society has become dangerously stratified and that an elite governs us and makes decisions about trade and war without enough consideration for the people who will pay the price.

When Webb critiques the accomplishments of our multicultural and tolerant and highly educated society as being spread across a thin veneer at the top, he’s telling us something insightful and urgent.

He may still have a tin ear and he may have a constricted worldview forged fifty years ago in the jungles of southeast Asia, but he’s still worth listening to because his perspective explains a lot even when it isn’t consistently fair or accurate.

Democrats cannot afford to have rural counties in this country considering them such an enemy that they won’t give more than 20% of their votes to the party. They want more decision-making power and more respect and a more secure economy. They ought to have those things, and the left better get to work figuring out how to give it to them.

And, to be clear, electing Donald Trump will not give them the kind of power I’m talking about, nor am I talking about giving them more power to impose on our lives. I’m talking about the kind of power and economic security that will benefit the people of West Baltimore and the people in the hollows of West Virginia equally.

As for respect, that seems to be in short supply on all sides right now. A successful response to Trump and Trumpism will find a way to bring truckloads of respect back to our political discourse, because that’s what it’s going to take.

“Every racial and ethnic group has wildly successful people at the very top, and desperately poor people at the bottom.”

This. The virtue of Washington Consenus meritocracy is soooo soothing. They are not interested is raising the fortunes of the working class in general; they want to facilitate the “deserving” to jump FROM the working class.

It’s true, but the proportions are very different for various groups. Also, while rural whites have certainly got the short end of the economic stick for a while, they don’t get hunted by law enforcement. It’s hard to be a poor white in Appalachia, but still substantially better than being a poor African-American in many ghettos – or in a rural area, for that matter.

It’s not that simple. My wife’s best friend in high school was African-American. Her father was a physician. They were upper middle class. Yet she could get into any school with full scholarship while my wife, who is white and middle class, was treated like everyone else.

This system of “affirmative action” is wrong. I’ve believed this for years. Rural people have a point when they call it reverse discrimination. We should try to boost the disadvantaged but the metrics need to change. We should help those from challenging backgrounds, measuring things like household income, the schools one attended (with under-performing schools considered a measure of disadvantage), and whether one’s parents attended college.

As for Bouie, I get his anger and outrage. I can empathize with him and also empathize with rural voters who feel disempowered. We need to resist the temptation to play the Republican’s game of turning one group of disadvantaged folks against another. These are precisely the people who should be sticking together. Those of us who are politically aware should do our best to ready the ground for a sewing of unity seeds that can lead to a unity harvest by having empathy for all (except those who are clearly acting in bad faith, such as open racists).

I’d like everyone to read the story here:

http://twitter.com/garyyounge/status/798872174085963776

It will be worth your time. It’s also further proof for what Boo says. Yes, we agree on something.

Boo wrote: “Democrats cannot afford to have rural counties in this country considering them such an enemy that they won’t give more than 20% of their votes to the party. They want more decision-making power and more respect and a more secure economy.”

They want more decision making power than their relative percentage of the population justifies, just as they ALREADY get MORE FREE STUFF than would be justified based on their contribution to the tax base. I say this from my seat of eternal frustration in West by Gawd.

You must know that a lot of that FREE STUFF is because our elites see fit to subsidize corporation bottom lines instead of raising the minimum WAGE so they could afford to pay their own damn way.

And there is this…

http://www.wweek.com/portland/article-17350-9-things-the-rich-dont-want-you-to-know-about-taxes.html

If you are in the west, you will see, in February, a revival of the Sagebrush Rebellion. The Rs are going to try to privatize public land.

You heard it here first.

The government’s job is to serve the COMMON GOOD, not to proportion it out according to the tax base. Obviously the rich areas provide more and the sparser areas get more. That’s as it should be. It’s called distributive justice.

The rich areas are vastly richer. And they depend on the countryside as well. Where do you think your food comes from, Central Park?

In fact, those sparser areas often DO NOT get enough services.

The problem is that the country areas hate the city folks, but not for that reason.

It’s really pretty simple. These people have grievances, they vote Republican and all the Republicans do is cultivate their grievances and help make them worse.

We know this, we’ve known it for years. What we have not understood, and need to understand now, is that the Democratic party has responded to the situation in a dysfunctional way, thinking that we can just get our own voters to the polls and continue to ignore everybody else.

Even the 50-state strategy was controversial. Because they had your attitude: Wadda we gonna spend so much money on these rural hick campaigns for? Not enough bang for the buck!

Wrong …

Did you get a big enough bang on November 8th?

I agree with much of this. I was repeatedly scoffed at, on this very blog, for suggesting that racism, perhaps, wasn’t the monocausal explanation for Trump’s popularity. However, the question, only real question, remains. We have two parties, neither of which gives an effective shit about Clay County whites. One party, though, uses racism and conspiracy theory poured through a toxic media funnel to appeal to those voters. The other does not. For Clay County whites, that’s the only difference that matters. They’re fucked either way, so they vote with the party that at least offers racism and scapegoating, and doesn’t mock ignorance.

Should the other party use racism and conspiracy theory poured through a toxic media funnel to appeal to those voters? Of course not. We can capture those votes by offering policies that ease hardships! That should be easy, given that the other party doesn’t give a shit, right?

Wrong.

Easing hardship via policymaking is not enough to capture these votes, because the other side is offering them something of value. Something horrible, but valuable. Obama gave Kentucky the popular and effective Kynect, and that didn’t change a single vote.

Which means, actually, that one party does give a shit, at least on the level of policy. The other party only gives a shit on the level of messaging. Given that we cannot use racism in our messaging, and given that effective policy changes alone doesn’t capture those votes, where does that leave us?

Keep in mind we’re not in a deep hole, notwithstanding Boo’s panic about rural districts. We only need a national swing of less than 2% for the Presidency and about 4% for the House. (Haven’t looked at the 2020 Senate – that might be worse). We don’t have to flip the rural districts, just get them back to where they were in 2008 or 2000.

IMO the biggest problem is that a lot of the trouble rural areas face is just – reality. There are many fewer jobs in farming or rural-suitable industry than there were 50 years ago, never mind 100, and our current auto-oriented chain store development pattern is expensive and not affordable on a working-class budget. There are tough economic limits on providing good-quality lives by modern standard in rural areas on the median income.

Whipped out my calculator and did a little math. 106k votes spread between PA, MI, and WI is all it took to toss the election to Trump. That’s a Saturday afternoon at The Big House. Gotta believe we can get that back.

This is why I have convinced myself that it is NOT economic anxiety. It’s race. Trump won rural whites when in his announcement speech he called Mexicans rapists and said he would build a wall to keep them out. He never backed down on the race baiting, and only went up in the polls.

.

It’s just wrong.

We lost because 16 percent of those under 30K switched from Obama to Clinton.

If it was about race they wouldn’t have voted for Obama, would they?

That is the question for which I am desperately seeking an answer. Because that will define the direction that I need to go. As in your example with Kynect, a wholly Democratic policy and effort gave a life saving and life altering opportunity to hundreds of thousands of rural white people. Yet the election still gave us this, virtually unchanged from 2012 results:

How in the hell do you even begin to decipher this or come up with a way to deal with it constructively and positively? Any clues?

Even more frustrating, they elected a dude governor who campaigned specifically on eliminating Kynect. Teh stupid, it hurts.

Does the Democratic Party there stand up for the accomplishments of the state or national party? Do you not remember the Grimes/Yertle the Turtle debate two years ago that killed Grimes’s chances? The moderator asked her if she voted for Obama in 2012. Grimes wouldn’t give an answer. What does that say to voters? It says that Democrats are cowards. She didn’t even make Yertle the Turtle own Willard.

Speaking as liberal Democrat, yes, in my mind she should have proudly and unabashedly said “Yes, I voted for President Obama”, and launched into a full throated defense of Kynect. I’m not sure that would have swayed a single Republican voter, but it would have at least let Democrats know that she was a fighter for Democratic values.

I don’t know much at all about the state of the Kentucky Democratic Party, Grimes was obviously an abysmal candidate, and was trounced by over 15 points in that 2014 Senate race. However, she won reelection as SOS by a two point margin in 2015. But she has espoused some pretty typical conservative views when it comes to guns, the ACA, the EPA and foreign policy.

That’s the whole point though. She’s the usual timid Democrat. And we all know why they’re timid. Gotta keep that campaign money flowing in. But then they have no answers when stuff like the last 6 years happens. And the Democratic Party becomes a nuclear wasteland as a result. That is what some people don’t seem to understand. Even if HRC had eked out an Electoral College victory, she’d still be presiding over a Potemkin Village of a party.

Yes, but which party tried to get them health care? And which party will take it away? Which party seeks to raise the minimum wage? And which party wants to do away with it? Which party tried to address the cost of college? And which party does not care?

The policies that Webb APPEARS to seek are there. But the media refused to talk about it, and Clinton went negative (nobody was listening anyway). Of course if those policies got close to being in acted Webb would immediately start ruminating about cost and the deficit. Trump blowing up the deficit with 1% tax cuts? Webb won’t say a word, even though the people who will eventually pay for those cuts are…..the working class.

It’s NOT economic, except in the sense that white working class in these areas are convinced that bucks are buying steaks.

.

That’s absolutely my point! One party didn’t just try to get them health care, one party actually did. (At least in some areas, such as Kynect.) The other party only gave them scapegoating and resentment. They chose scapegoating and resentment.

However, did we tell them that we gave them Kynect? (And no, it’s not enough to blame ‘the media.’ Managing the media, or making our own, is our job.) Clearly enacting helpful policies isn’t enough. And clearly racism, nativism, misogyny, anti-elitism, etc., is enough. Just barely, but enough.

So. What was our failure? I know what the voters did wrong. But what did our party do wrong? We need to answer that, if we’re going to fix it.

Democrats ran, and run, from democrat accomplishments. That would be one failure.

Look at this diary! Right before the election, when everyone thought Clinton would win, Chris Fucking Mathews said Clinton (as POTUS) would HAVE to reach out to Trump voters (white people). Now that Clinton has lost, what is everyone saying? Democrats HAVE to reach out to Trump voters. And the so called progressives on this site AGREE! And who does Booman pick as the ‘reach out to white people’ spokesman? Fucking Jim Webb, the poster boy for republican lite. The guy who almost certainly says in private ‘I agree with a lot of what he says’.

Think about Trump voters….they voted for a reprehensible person, with no moral code whatever, knowing he was going to make the lives of POC absolutely miserable for at least four years. Knowing he was going to take health care away, knowing he would kill environmental rules. They ARE deplorable! She was right about that.

Yet now so called progressives, the ones that so desperately wanted a democratic reset, now want to take Webb’s advice and reach out a hand.

It’s quite amazing.

.

So what’s your specific suggestion, in terms of what we do now?

First, and most difficult, get a nominee that the right wing media has not defined for voters. It’s extremely unlikely any nominee will be defined like Clinton was (nor have the self inflicted wounds), but we know republicans learn their lessons well, and any potential nominee will almost certainly face congressional investigations.

Next….right now the base of the party is facing very hard times. Trump has opened the racist Pandora’s box. He’s appointed a bigot as chief advisor. The democrats HAVE to have the backs of minority’s. That is their base. Tied to that, congressional democrats HAVE to fight like hell over Medicare and SSS. The ACA is gone, but they need to be clear who killed it.

In other words, the democrats have to show principles. In a way, this is the opposite of appealing to whites (as it’s being defined by Webb). Isn’t principles what progressives have been demanding? IMO going specifically after whites is not principled. It’s abandoning its base to the wolves.

That would be a start. Stand up for something. If they can’t do that, then they deserve everything that happens to them.

As a side note…isn’t it interesting that appealing to POC is considered identity politics…but appealing to white grievance that throws POC away is considered smart politics?

.

So nominate basically any other candidate, call out the Republicans for racism, and fight for Medicare and Social Security?

If you’re right, we’ve got this in the bag.

I am for reaching out to Trump voters who voted for Obama twice.

Please explain how this is wrong.

In all of this stuff I think there is a tendency to confuse the average Trump voter with the swing Trump voter.

These are very different things.

It is easy, because the consequences are so enormous, to overstate the problem here. We lost pretty narrowly in WI, MI, PA and Florida.

There are certainly things to understand: the swings in Iowa and Ohio were larger and potentially lethal to any hope we have of holding the Senate.

I certainly believe that there are issues Bernie raised that need to be considered. I think there were things unique to Hillary that highlighted deeper issues we have with downscale whites.

I just caution against over-reacting, or against thinking that the political situation is hopeless longer term.

We will never reach these voters. They live in the fox news breetbart bubble. There is no democratic message they will hear, let alone respond to. Until there are national consequences for being a public liar, there is literally nothing to be done.

Since the election I’ve gone back and forth between these two viewpoints – that middle America deserves sympathy and help, and that people who voted for Trump elected a racist and should feel accountability for that.

Facebook was really odd after the election. Predictably, liberals were sad, angry and upset. But the conservatives didn’t celebrate – instead I see angry posts about how smug liberals are, and how Trump won’t be that bad and conservatives don’t understand why liberals are panicking. They don’t sound happy.

So about that smugness: I live on a coast and I have a graduate degree. I’m proud of it. When I left the South for college I had friends gently point out that some of my assumptions were actually kinda racist, and I argued with them. It took me a few years to start to understand, but I finally believed them and changed, and I’m proud of that. Before Obamacare I was independent contractor who couldn’t get my pre-existing conditions covered. Flawed as that bill is, I am proud it got done. Is all that pride what makes me smug? Because I’m going to still be proud of those things.

Before this election I was already sympathetic to workers who have seen their jobs disappear and to those who have not had my opportunities, and I will try to be more so.

At the same time, even with the opportunities I have had, I have worked insanely hard and will still struggle to buy a home or retire. That someone would vote against me but in favor of the 0.1% is strategically crazy, but that’s what happened.

All that resentment against the “elite” didn’t appear out of nowhere. We need to fight that term. It’s masking things of true value that should be protected, and it’s not addressing the real issue of economic and social mobility, or of the feeling of isolation at the center of the country.

Soft peddle the racism condemnation it if it saves Medicare. Because Medicare will help me as a non-white eventually. Otherwise I’ll just have to die quickly.

We need to be able to straddle that line. I wrote this at the tail end of the last thread but it applies here

I don’t think you can ignore racial/gender politics altogether though. People of color have every reason to be wary when D start saying things like we need to just move away from racial/gender politics because history has shown more often than not when Ds decide that economic issues supersede any and all racial and gender issues women and people of color get left behind.

For example progressives cite FDR and the New Deal as what we should aspire to now but they never acknowledge that the New Deal, including social security, was deliberately designed to exclude people of color. Social security did this by excluding sectors that were filled with a high percentage of people of color. They also never acknowledge that FDR threw anti-lynching legislation under the bus to keep his New Deal coalition in place.

This is also why progressives saying that Obama should have welcomed their hatred like FDR did was very tone deaf. Sure FDR said about Wall Street when he had the advantage of not only being part of that club (old money white male) and when he had congressional majorities both sides only dream of today but he certainly never said that about racist southern Democrats in the Senate.

My point in all of this is that there has to be a balance and that when moving forward on a more economically progressive message the party needs to ensure that people of color and women know they won’t be deliberately left behind as they have been in the past.

I think POC realize that when ANYBODY starts talking ‘we need race neutral policies that address the working class as a whole’ they know it will address them last, if at all.

Clinton won the under 50,000 income by a large margin. Not as much as Obama, but not by a little. Trump won over 50,000, and as income went up, his margins also went up. In other words…the ‘elite’ voted for Trump. Why? Because the ‘elite’ votes for the republican.

.

True. I’m talking more about Cramer/Hochschild experiences than the twitter shame-fest that goes on all the damn time. I supported it recently but we’re not numerically there enough to do that. That means that you need to address the systemic racism and inequalities at a policy level, but on a personal level the kind of demonstrative shaming is counter-productive in the extreme and will result in lost elections which will set back progress institutionally by years and years if not reverse it all together.

It’s too bad we can’t dogwhistle to minorities. Unfortunately we haven’t done a very good job on addressing BLM issues even in true blue cities and we don’t have a lot of credibility there.

Of course, we’ve all been thinking about these topics since the election. What I think is being described is the concept of “agency”. That is: being in control of your own life, of decisions important to you.

What the “elites” do is make policy for other people: bathroom laws, cake laws, whatever. The elites on the court support those. The elites screw up the economy and stiff millions of people on the value of their homes (if they could even keep them), probably the only significant asset they ever had, that they worked 30 years to pay for. And then those elites don’t pay any price for their misdeeds. The towns folks live in die because Walmart and Home Depot and Hobby Lobby move to the town 25 miles away, the one with 25,000 people, and so the store owners in the town with 2000 have to close up: the lumber yard, the hardware store, even the grocery. All that those folks are left with is a Dollar Store (maybe) or a 7-11, and they had no choice in that at all. And they are helpless to do anything about it.

Sure, one can go back to the VietNam War. It doesn’t matter where the punctuation is, where the story starts. This is the state of things. No one has an answer to revive small town, rural counties. There is no policy cure. So policy doesn’t matter. Just the outrage does.

I certainly have no idea how to give a great sense of “agency” to those folks. State control of Medicaid? School boards? I don’t know, but I’d be interested to hear ideas.

Just one more thought about this campaign. Clinton, surely a flawed candidate, did not have a single moment that I saw where she had a truly human interaction. In 2008 she turned the tide in NH by a simple moment of unscripted vulnerability. There was not a single time in this campaign. In the one town hall “debate” where she might have made that connection, Trump so squeezed her out that she couldn’t even do it there. Genius on his part because it truly was a vulnerability for him (to allow her to be human). Ugh!!!

Maybe we should have titled it: How to make progressivism great again.

I heard two days ago that Clinton loves hot sauce. Loves hot peppers, too–one of her aides carries around raw jalapeños for her to snack on during the day. So goofy and eccentric and adorable. Never heard that before, and a quick Google tells me that it’s actually true.

Like just almost everything people criticize about the Clinton’s campaign messaging, they did try to publicize it, and the media largely ignored it, apart from a few mentions in elite-directed publications like the Atlantic. Salon, typically, asked whether Clinton’s well-documented 20-year-plus obsession with hot sauce was a fake-out to seem more relatable. Seriously.

With friends like these…

A half billion dollars, they couldn’t push that into public consciousness? With all the expert marketers and the best PR people in the country, with every high-wattage celebrity in Hollywood, they still couldn’t command unearned media?

Maybe not. Maybe the media is insufficiently responsive to money and celebrity and establishment connections. Who knows? Certainly I don’t think hot peppers would’ve made a difference. I was just expressing surprise that there was such a cool fact about Clinton that I–who followed her on Twitter, and read the elite-directed publications–had never heard.

Blaming Sander’s loss on the ‘establishment’ is stupid; fighting a hostile establishment was baked in. Blaming Clinton’s loss on the ‘media’ (though I do, I do, I do) is equally stupid: fighting a hostile media was baked in. But who cares, at this point? Pointing fingers is fun, but learning lessons is better, and I’m not sure what lessons we should learn.

I agree Clinton could have done her messaging differently. Still, that half a billion gets surprisingly little exposure, compared to Trump’s over 2 billion of free media. Yes, she should have run against the Republican Congress more and Trump less, because the media was willing to talk about p*ssygrabbing and such, at least a little. But part of the reason I’m beating the “the media is very hostile” drum is that a lot of the problem with the Clinton campaign is that they didn’t realize how hostile the media would be. They put out one great position paper after another, on a regular release schedule, figuring the media would put out digested versions for mass consumption. But the media never did.

Some have suggested she should have put out bite-sized hyped positions to reach the public but if she had done that the media would have dissected it and criticized it as inadequate/unrealistic/etc. There is a road to walk, of good proposals with pithy and mildly overreaching twitter links, but it’s quite narrow, and it’s important Democrats in the future realize they have to walk it.

there was no oxygen for anything that wasn’t tied to Trump in some way, her media strategy reflected that

Seriously, regardless of the veracity of Hillary toting around a personal bottle of hot sauce, her campaign did tout it to apparently make her seem more like ordinary people and therefore, one of us. Hot sauce? I’ve never known anyone, even people that love the stuff, that doesn’t leave home without a bottle of hot sauce. That’s why it looked fake and combined with the fact that hot sauce (or any other specific foodstuff preference of a candidate) is so insignificant that the PR effort on this failed.

Beyonce carries it too. So did my son for a while.

There is a policy cure.

I suggest reading: “When Corporations Rule the World” written by conservative David Korten – Originally published: 1995

I seem to have a knack of finding books that end up predicting the future. It started with: The Media Monopoly written in 1983 by: Ben Bagdikian…

The complaints of the people in Cramer’s article scream “passivity”. They’re not getting things. They’re voting for the guy who can fix it for them. This complaint is about lost entitlement and privilege.

I come from this with a little different perspective than some others.

My father is an immigrant who came to this country with absolutely nothing. Unlike others who never had anything before they arrived, my father’s family’s great wealth was taken away from them by Communists in China (my father is Russian however).

He did not have education beyond a high school degree and had no time to go to college. He had to go to work immediately upon arrival to the US to support my grandparents. He also was drafted into the army for Vietnam yet before he was granted citizenship. And yet he proudly served the country nonetheless.

Despite the vast wealth that was stolen from them (imagine eating cavier daily for breakfast in the 1940’s), my father was never bitter about what happened to his family and succeeded in this country beyond what one might imagine could be possible.

But he did it by going where opportunity existed and trying new things when necessary. He always had an open mind and never took the answer “no”. I respect that more than anything.

I do feel for the rural folks who are suffering in towns across America. I really do. But respect is earned not given. Remember that. If your family has lived in a town for generations and the jobs are gone, why do you remain? Nostalgia??? Might you consider moving to where the economic opportunity might be? Unlike my father who had to move continent to continent to find opportunity, they may merely have to move to the closest urban center. Worst case scenario they move across the country. They may even have to retain.

Yet none of that is anywhere near the disruption my father and his family endured. If my father could do it along with the millions of immigrants that have come to this country since its founding, these folks can as well.

I recognize this might not be what people want to hear and it likely is not helpful for Democrats electorally. But when millions have come to this country for a better life and have endured much worse to succeed, it is very very hard to feel empathy for those who have the opportunity right in front of their faces and are unwilling to get off their hind legs and grab it. And it is very very hard to see what my father and millions of others have endured to succeed in this country and then be asked to have respect and empathy for “rural” folks who want that same success, but are unwilling to go through even less discomfort and disruption to get it.

That’s all fine.

But if I just change the characters it reads differently.

Why, for example, haven’t blacks in this country just moved out of urban hellholes to where there is more opportunity? Why not quit your South Bronx apartment for a place in Midtown?

Well, you know there are things like redlining that help explain this. But a lot of it is lack of capital. Now, your father initially had a capital problem, too, it’s true. But you can’t use the go-getter as the example because they’re always the exceptions. Most people get left behind or are ruined in such scenarios.

We can’t just tell everyone in rural America to relocate to the cities and out hustle each other.

Personally, I think you’re going about empathy the wrong way. Not to get religious, but Jesus didn’t say that people needed to get up by a certain hour to be blessed.

And I will add, as I tried to state above, the value of the homes fell in 2007. So these folks, farmers and small business people in rural towns, couldn’t even sell their homes, or get a price that represented even a good part of what they had invested their lives in. And for farmers there is a passion about the land. My brother-in-law, a farmer, has to figure out what will happen to his farm since the kids don’t want to farm.

The kids left. So again, what they might have hoped they were building for their children became worthless.

And factory workers? Well, they can sell their houses for next to nothing and retired to Florida or somewhere and live in a trailer. They are too old to be retrained, even if they moved. No computer skills. Can’t type. Too old to “transition.” There is a powerlessness about it all. They’re just left to rot in their rotting towns.

Some folks have pluck. They’ll leave for the cities, get educated, etc. Your dad did that under some set of circumstances. But most folks don’t do that. They just sit tight and hope for the best. This time someone came along and promised the world. They fell for the con.

An important issue is intellectual capital. Even if you take away of a wealthy person’s money, they still have their education and their skills at managing, self-control (from an easier life), and negotiating. This is truer than ever in the modern economy, where almost all good jobs require a college education. If you went to a rural high school without a good college track and you’re even into your 30’s, you’ll probably never be able to get a good job anywhere. Yeah, you’ll probably be somewhat better off in some metropolitan area but not enormously so and moving is expensive, both financially and socially.

It’s this kind of thinking that has gotten these rural folks in the mess they are in:

“If you went to a rural high school without a good college track and you’re even into your 30’s, you’ll probably never be able to get a good job anywhere. Yeah, you’ll probably be somewhat better off in some metropolitan area but not enormously so and moving is expensive, both financially and socially.”

They can’t get trained to be a plumber or electrician in their 30’s? I don’t buy it.

Tons of jobs there (and primarily only in urban areas). In fact, I know several individuals who came from nothing and became plumbers and electricians. They are much wealthier than I am and I have a graduate degree.

I will repeat it. To succeed you have to get off your hind legs. And you will have to accept disruption and discomfort along the way both financially and socially. You might have to live on Ramen noodles for awhile and near an ethnic group you don’t like or (gasp) live in an area that supports gay marriage. But you can succeed.

Well, here’s info on becoming an electrician:

1) Take the right high school classes.

Oops already if you goofed around in high school, or focused on sports, or whatever.

2) Get an associate’s degree.

Difficult in Clay County, I’m sure. So now our hypothetical upwardly mobile rural dude already has to move to a more urban area and somehow support themselves for two years, with probably pretty minimal social support.

3) A year of apprenticeship

Now they need some contacts in their new area, plus another year of mediocre wages.

4) Get licensed.

Usually with a test – a nontrivial hurdle for a lot of people who have trouble with tests.

Impossible? No. But, genuinely, it’s hard. For somebody with kids, maybe a broken marriage or a family member who needs support, or almost anything else tying them to a local, extremely difficult. Not everybody can do this, and I don’t think they should have to.

It’s not easy, but associate degree? No. you don’t need any college at all, and you do not need to take special classes in high school.

And I live in California, where it is a special trade.

.

.

“Impossible? No. But, genuinely, it’s hard.”

Correct. As was coming to this country with no job prospects, no college education, no friends, no acquaintances, no knowledge of the culture, etc. for my father.

Life is hard. Sometimes extremely difficult. And you are right that not everybody can do it. But when the status quo is worse, I think they should try. And, guess what? Even if they fail, I will respect them a lot for trying.

I am a liberal. I support programs like Medicare and SS and think that government should provide a robust safety net.

But in the end, life is what you make of it. If you want to stay in your small economically depressed rural town because your family has done that for generations and be bitter at everything, be my guest. But don’t ask for my respect.

Lot of correct statements in this.

The recent book “Hillbilly elegy” is about the Appalachian people of S Ohio and N Kentucky and thereabouts. Part of it is a description of things done to them.

Part of it is a savage, uncomfortable and unsympathetic self portrait. He talks about people who are too stupid to keep a job. He talks about people who quit jobs because the jobs make them get up too early in the morning. He is NOT HAPPY about the lazy stupid people who are his relatives. He does NOT cut them slack. There are a lot of people who are lazy and stupid.

Meth mouth is a choice not an echo.

This is exactly backwards:

But respect is earned not given.

This is wrong. One is owed respect by virtue of being human.

You are actually very conservative.

You are literally repeating Horatio Alger.

And specifically what is the problem in repeating Horatio Alger?

What is wrong with telling people that working hard is good, that working to improve yourself is good? Those sound like good ideas to me.

We need people to want to improve themselves.

And sometimes YOU are the problem that YOU are having. People can have habits that are bad. Like drinking too much or taking drugs.

Taking drugs is a moral failing. Sorry, it is not a disease. It’s a moral failing. Because no one is born addicted to meth. You get addicted by taking meth and enjoying it.

I took a lot of drugs in college. I dropped acid a bunch of times. But I never used a needle, not even once. Because I knew that it was probably too much fun. So I never did it.

But stupid people shoot up all the time. Because they are stupid.

Hard drug use is and has always been a slow form of suicide. Sure some people tried to “party” and just got caught up. But for most people depression was the instigator. Seriously.

“but for the grace of god go I”

I agree some. Opioid addiction is a combo of;

People certainly (I think) know that o is addictive. They do it anyway.

It’s a huge problem.

“Taking drugs is a moral failing. Sorry, it is not a disease.”

Congratulations this is most ignorant statement that I’ve seen on this site. Pretty hard to do but you managed to do it. I suggest you educate your self on the topic.

I am certain that I know a whole bunch more about opiate addiction, opiate dependence, the reasons why people take drugs, and so forth. Having taken my fair share (years ago), I understand the lure of drugs. As a person who doubtless drinks more than he should, I still participate in drug usage.

Getting involved in opiate use is not a disease. It is a choice. No one is born addicted to opiates. Everyone who is dependent on opiates takes them, and they take them in CLEAR KNOWLEDGE that the drug is addictive. That is a moral failing. If you choose to become an addict, that is your problem. Once you are an addict, you need help getting off the drug.

But no one is born an addict. You become an addict by making choices.

1 – Your first sentence makes no sense. You need to know “more” than someone. If you are implying you know more than I do on this topic, it is obvious you don’t know what I do for a living and I can guarantee you that you are dead wrong.

2 – “no one is born an addict.” – Babies delivered to mothers that are on drugs can be born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) – basically meaning they are born an addict.

3 – A simple “No thank you, I choose not to educate myself.” would have been sufficient.

it’s the eternal mystery of my personal life. Why can some walk away, and others are gone, forever?

Addicts can also be made, I have no doubt about that.

.

Wisconsin has elected and re-elected Scott Walker three times now. He’s given them exactly jack and shit. I’m supposed to feel empathy for these people and their self inflicted wounds? Here’s some advice; stop punching yourself in the face.

And the Democrats responded in ’14 by running Burke against him. Not a smart move at all.

And how much of that led to it’s going Red this year? What ever you want to do, think about what the outcome is going to be.

And what alternatives did they have to choose from? The Dems have offered nothing for these people for years and years. Neoliberal elite nonsense is all they have heard.

I supported Bernie and many of us feel the exact same way.

Empathy – No.

……………………Pity – Perhaps.

…………………………………………Emnity – Yes.

…………………………………………………………….Derision – Always,

I can’t help but think that so much of these voters’ “beef” is the product of a deliberate campaign to deceive them. Do rural voters have less of voice. Do the taxes of poor rural voters subsidize the poor in the cities? Do rural voters not get respect? Obviously, I think the answer is “no” across the board.

If we’re unable to overcome the lies of the GOP over the past 40 years, why do we think we’ll be able to overcome the lies of the Drumpf administration?

The school yard always has a bully. It’s when he or she is ineffectively resisted that bullying blooms. Chris Hedges is right when he says this is the fault and failure of the left. If we do not enlist the power of truth to confront these morons, we will have the dismal future so many of us fear.

I recommend Cramer’s book highly. It’s of interest to activists in Wisconsin, for sure, but there’s a lot in it that’s much more general and broadly relevant.

Her methodology is both radical and innovative. She took the highly unusual step of going out and talking with the people she was trying to understand, and then includes their statements — unedited! — in the book. It’s as though she were letting them speak in their own words. Crazy stuff.

The first quote from Cramer sounds almost identical to how my mother’s upstate NY relatives spoke in the 1960s about NY state government. (Replace “a bunch of rednecks” complaint with “a bunch of hicks.) A difference was that most had a high school education and decent enough paying and secure employment. In turn, most of their children completed at least an undergrad college degree and the parents enjoyed a comfortable and secure (and often long) retirement. (And they were all Republicans as well.)

Racism wasn’t absent from that world. The Germans, the Italians, the Poles, etc. didn’t intermingle. They had their own stores, churches, clubs, and for the most part their own schools as well. “Marry a good German Catholic” was the one thing my grandmother asked of her children. She never got used to the Irish d-i-l but had to adjust to the reality that good German Catholics were hard to find. In 1990 at their once thriving German-American club, two of my received some sort of membership award. I asked how L who was Polish and J who was Swiss could even be members and was told that beggars can’t be so choosy these days.

The first thing we kill is this dubious idea that America is divided or polarized or whatever. This is a purple country and everybody–urban and rural–is in denial about it because of fear. Ridiculous, distorted, fantasy-based exercises like this pile of shit from the NYT don’t help:

That and other, nastier gloating by the likes of Geller et al perpetuate the destructive myth that the USA is divided beyond help, I said as much in AG’s diary.

I also said this:

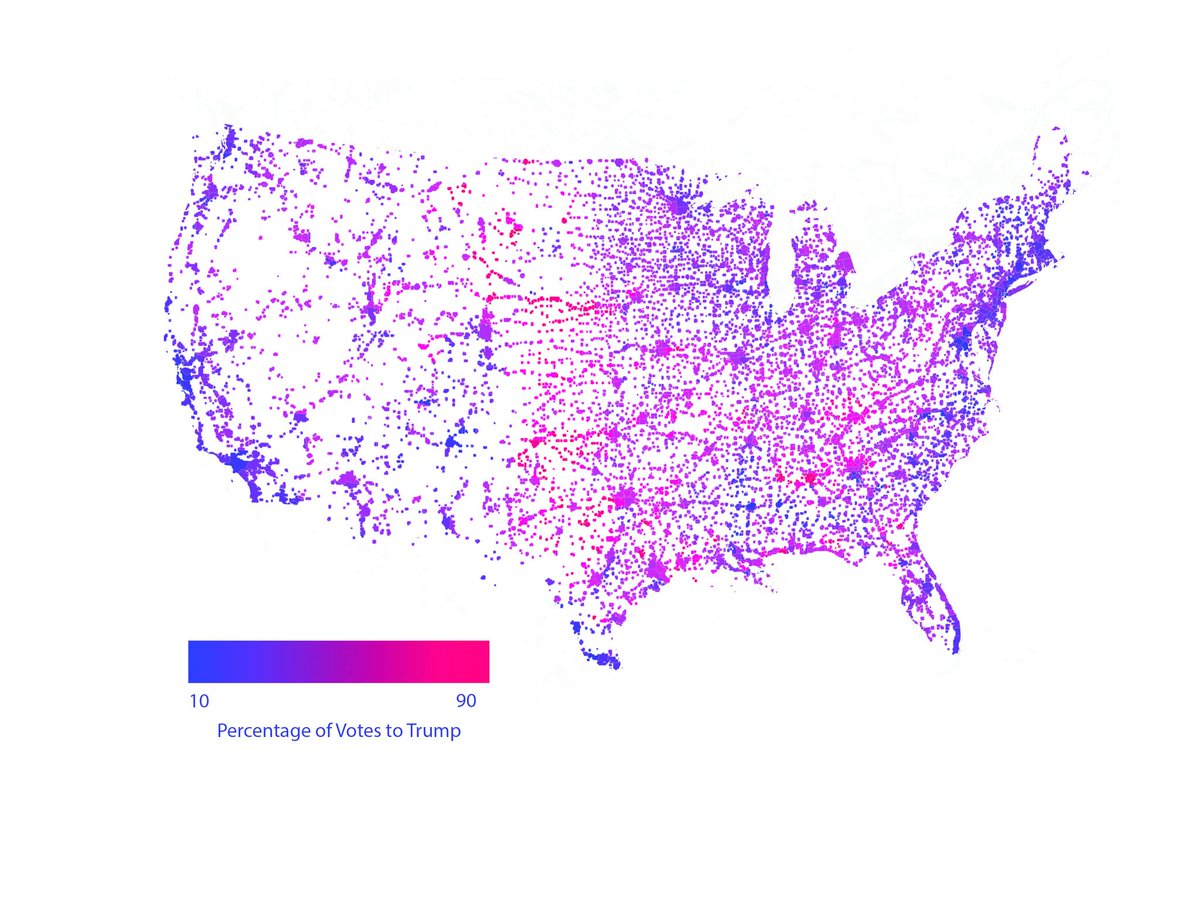

A more responsible representation would be this, distorted for population:

Or this one–a map of people instead of counties or states:

As long as we keep buying into this silliness about polarization, we’ll fall for the word “mandate” every time.

Sorry, the bad NYT map should be this:

God I hate that thing.

are those undergound aquifers or something in the bad NYTimes map?

You might say that, yeah.

Here’s another good one: a cartogram that shows the regular red/blue bloat but also those who didn’t vote for either. I’d like to see one that shows the percentages of how many didn’t vote, too.

These people believe the elite are ignoring them, and the GOP isn’t looking out for them, so they elect a billionaire and more Republicans? That makes no sense. What do they think they are getting out of this deal? That’s what we need to know. All I can see so far is vengence. If they’re going to hurt, so is everyone else.

Check the link I posted below. I found it interesting and insightful.

well, some just want him to say “you’re fired” to a lot of ppl in DC – but of course he can’t. many ppl were faced with a choice between two candidates they hated and chose the candidate they hated less. but that leaves the problem of what now? since it’s unlikely the Rs will address any of the problems they become more pressing

Michael Moore doesn’t like it either, but he absolutely understands it, and he explains it better than anybody:

http://www.thegatewaypundit.com/2016/10/real-michael-moore-trumps-election-will-biggest-fck-ever-rec

orded-human-history-video/

Here’s another one. I don’t know who this guy is, but he’s brilliant, brutally honest, and very angry. Warning: explicit language. Painful, but cathartic — if you can take it.

WHAT HILLARY CLINTON DID WRONG

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I67iRM6ijMs&feature=youtu.be

wonderful, thanks for the link!

http://www.cracked.com/blog/6-reasons-trumps-rise-that-no-one-talks-about/

Here’s something I ran across today that I found interesting. Another person’s viewpoint on rural America.

Like others, I’m both sympathetic to their plight but frustrated with their chosen “solution,” which will end up royally biting them in the butt. More taxes for them and us, while Trump cuts taxes major league for himself and his pals on Wall St. Way to stick it to the Elites!!

As others have commented, a huge issue is messaging and the great rightwing propaganda wurlitzer. This young man (in the link) also discusses the role that churches play in these communities. I understand that role and its appeal, but sadly so many of these churches have been infested by cynical hucksters trained by The Family/Fellowship (of National Prayer Breakfast fame, amongst other things). I’ve attended these churches, and they’re nothing but propaganda mills for the same sort of negative drek spewed out by Fox, all the rightwing shock jocks, and various “Christian” Broadcasting networks.

My beef is that the Democratic party rarely ever discusses the great propaganda wurlitzer in any meaningful and engaging way. There have been sporadic attempts – by Al Gore & Al Franken, to name some – to start some sort of “leftish” network to counteract the damage inflicted by rightwing propaganda to little avail. And of course, NPR is now basically Fox Lite and I rarely ever listen to their fake “noise” shows.

What to do? I see the media juggernaut as a huge part of the problem, and at this point, I have no solutions.

This one thing to grapple with in regard to this issue of the rural poor, who are not all white, either.

I understand that role and its appeal, but sadly so many of these churches have been infested by cynical hucksters trained by The Family/Fellowship (of National Prayer Breakfast fame, amongst other things). I’ve attended these churches, and they’re nothing but propaganda mills for the same sort of negative drek spewed out by Fox, all the rightwing shock jocks, and various “Christian” Broadcasting networks.

And yet every president, Democrat and Republican, attends those damn breakfasts.

It’s an interesting perspective and yet the whole “culture wars” angle seems like a dead end in terms of political analysis. Just way too much amateur sociology and axe-grinding.

That’s not to say there aren’t real problems in rural America that Democrats could do well to reckon with, but by that I mean real economic and quality of life issues.

I agree that the article doesn’t do much in terms of figuring out ways to deal with the issues of rural poverty. It is just one perspective on why there may be so much enmity on behalf of the rural parts of the country towards what they perceive as urban/city elites.

I learned something from it, and I think it holds some truth.

Where one goes from there in terms of coming up with solutions is another story. I think ignoring these people and writing them off as assholes and racists doesn’t help anyone.

I get caught up in the contradictions. We’re rugged individualists, we take care of our own, but everything is your fault and why are you ignoring us?

Yeah, well I think that’s simplifying it a bit, and I think, too, we get caught in political propaganda that says this is what these people think and believe. I’m not so sure that they’re all that into the rugged individualist nonsense as is advertised. Some are, but not all of them.

But yes, people are contradictory. Anyway, it’s one perspective and certainly not providing much in the way of solutions. Just something to consider.

Here’s a good example of what you’re saying:

https:/www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/11/13/why-these-rural-white-gun-owning-guys-didnt-v

ote-for-trump?tid=hybrid_experimentrandom_2_na

This suggests that “rural resentment” is a big part of what’s changed Wisconsin so much in the Walker era …

http://womenfreetime.com/news/how-rural-resentment-helps-explain-the-surprising-victory-of-donald-tr

ump.html

from the Ozarks:

http://lasvegassun.com/news/2016/nov/11/former-las-vegan-what-the-trump-vote-says-about-th/

The Atlantic is having a reader-response feature, and people from all over are responding. It’s very interesting.

http://www.theatlantic.com/notes/2016/11/i-voted-for-the-middle-finger-the-wrecking-ball/507533/

Because the “new economy” is crushing them, that’s why. It’s not like Wall Street etc. is neutral.

Thanks for posting that, I did learn something from it. I hope you saw the two I posted below, one from Michael Moore, the other “What Hillary Clinton Did Wrong”.

As far as solutions? I don’t know, but I would start out by talking with people in all those areas who are Democrats or independents or Berniecrats and ask them what they think. Because I’m sure that’s the best way to start. They know the territory, and the very fact that they want to dialogue with you constructively is a good sign, because not everybody does.

Add then with their help, get some small forums together and LISTEN to their problems, including problems of getting the national party to listen to them, or to support their campaigns.

As to the issue of: well the rural poor should move to where opportunity is….

Well how’s that going to work out? First of all, many of these people simply don’t have the money to do that. As some have pointed out, since 2007 or so, those fortunate to own a home are probably SOL in terms of selling it to make enough money to move somewhere else.

Even if you have money, where do you move to? Most urban areas these days are pretty darn expensive, even some of the smaller cities aren’t that cheap. If these people don’t have good education and training for different types of work, what are their prospects? At best, possibly working for minimum wage, part time, at WalMarts and similar. May not be much of a step up – or even step down – from what they have now. These people know that, as well, but check the link I put in my comment, above. The author describes – probably fairly accurately – what these people face, financially/competency-wise/educationally/psychologically, in order to move elswhere. And how do you decide where to move, especially if you really don’t know.

It’s not an issue that’s easily resolved by moving people somewhere else, no matter what. And some people simply aren’t capable of doing it for a host of reasons, such as medical issues, mental health, the need to take care of ailing family members, etc.

I surely don’t know what the soluton is, but I can see that sweeping it under the carpet and ignoring it in the hopes that it just goes away does not seem sensible anymore.

Sadly I seriously doubt that Trump will do one damn thing to improve these peoples’ lives. IF I thought he would do something beneficial, I might be more sanguine about all the horrible crap that’s coming our way. Sadly, I think these very people are about to be royally shit on in worse ways than they ever imagined.

I hope I’m wrong; I doubt that I am.

still wondering how, for example 38K people in Boston, became rural

You wrote a great piece but there’s no solution there. HRC was already offering them far more than Trump. Perhaps, she was the wrong messenger. We can try someone with more populist cred next time. What if that doesn’t work either?

Clinton did offer more and probably better solutions than Trump. Clinton’s “problem” was that she didn’t travel out to these rural areas and really talk to these people. Trump did.

We may dislike Trump’s style, but to give credit where it’s due, Trump traveled like a maniac and visited hundreds of rural areas and small towns. He recognized these people and their very real problems.

Clinton may have recognized their problems, but she didn’t go out and TALK to them and TELL them what her solutions were. Ergo, they saw her as yet another elitist mainly visiting cities and talking to other elites.

It was a huge error on Clinton’s part, imo. Having good solutions listed on your website is fine, but you really need to get out and talk to these people face to face. She lacked credibility in that regard.

f

OK. Why? She didn’t got out to rural areas at all. Had she campaigned there more, why do think that wouldn’t have mattered? I’m serious. Would like your insights.

You act as if he was out doing retail politics in Lake City, FL. He wasn’t.

Look, I am not trying to be difficult, here. I am simply saying that winning back the WWC and WLMC may be really hard. Other than putting forward someone who is more credible to these people (e.g., Warren), I don’t know what Dems can do. There is no getting away from the hostility many feel toward nonwhites.

We don’t need to win them back as a group, though. All we need is the 10% or so we lost in this election, and the New Democratic Majority will be in full swing in 2020, with a very likely presidential win and a roughly even race in the House, the gerrymander notwithstanding. We know those are winnable, because we won them just 4 years ago, with an African-American candidate even. Actually, even if all we do is keep from losing anymore of them, demographics will probably put us over in 2020.

It’s a fairly easy lift policywise, and morally commendable as well. Americans shouldn’t be stuck in hard lives with limited options because of accidents of births.

Have you ever run for office? Your glib statements about “the 10% we lost” suggest not.

It takes an earthquake to move a district usually. Remember 1994, when Tom Foley lost and the Rs won the House? Probably not. The Dems lost 110 seats. How? The NRA killed them. One of the only times a sitting Speaker lost in an open election, due to the NRA.

That’s the kind of earthquake we need.

Please give me an issue which we can get 110 seats to move to the Ds.

Thanks for your response. I appreciate it and don’t disagree with your insights. That said, are you aware that a somewhat significant portion of these voters actually did vote for Obama in 2008?? And that’s likely partly why he won.

I don’t think, as a block of voters, all of these people are racist. Certainly some are, and they are mostly loud about it. And they get a lot of media attention. I don’t like it either, but I think it’s a mistake to figure that everyone in rural areas are simply racists and won’t vote for Democratic politicians. I don’t believe that’s the case.

Getting a credible candidate is another story, although, while I wasn’t his hugest fan, I think Sanders would have done much much better than Clinton with this particular cohort of voters. JMHO, of course.

Neither McCain nor Romney ran on an explicitly whites-first campaign. Reportedly, in 2008, Obama’s team workshopped racist ads against Obama and they were very effective. Thankfully McCain didn’t go there

I agree with you, but we need to reach those voters and that’s a big problem. First the Democratic Party has to stand for something, and second, they have to get the message. The right wing absolutely dominates communication in most of the country. We’ve got to figure out how to break through. Some won’t listen, but many will I believe.

Incidentally, there were some victories, and of course some defeats for Berniecrat candidates around the nation. Here is the scorecard:

https:/ourrevolution.com/election-2016

I’m proud of all these people.

There was a piece in the NYT magazine by Nikole Hannah-Jones who went into Iowa and interviwed voters who had voted both Obama and Trump.

All (or most) turned out to be racists who had set aside their racism for more pressing urgent concerns, but Trump was able to get their racist juices running.

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/11/20/magazine/donald-trumps-america-iowa-race.html?rref=col

lection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fmagazine&action=click&contentCollection=magazine®ion=ra

nk&module=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=sectionfront&_r=0

It would have mattered; show ppl she’s interested, give a chance to see her a different way. otoh if she’d have done that she wouldn’t have been as flawed a candidate as she was.

Just because you talk to them does NOT mean you convince them. It just means you talk to them. Convincing an R to vote D is a genuine difficult task.

Agreed. But how much good does ignoring them do? A LOT of people from those rural areas voted for Obama in 2008 and for Bill Clinton in 1992.

For sure, some of those voters will never ever vote Democratic, but some do switch back and forth. Or, at least, are open to voting Democratic.

On top of talking to them, the Democratic party really needs to push credible programs to aid and assist these people, but I realize that’s like pushing boulders up the hill due to Republican obstructionism. But we need to TRY and be SEEN as trying. HOW is that accomplished? By seriously TRYING and talking about it. I don’t see that happening so far.

Oh, making the effort is highly important. Agree 100% with you there. Going to the coffee shops, talking to the Rotary Club, etc. Going to 4-H meetings.

Please don’t consider that I am discouraging this. But we do need a message, and this will take some thought.

The message has to be based on THEIR problems and THEIR feelings. Rhetoric 101.

That’s why we need a lot of local talent. People who understand the local situation and communities, not just some slick Washington consultants. They’re out there.

Yes, but there’s also independents, and there’s also Democrats who just don’t vote because they don’t see anything to vote for, or don’t even know who’s running. There’s also first-time voters or other young people who may have different problems and different outlooks than their parents, as we saw big time with Sanders.

Are we talking about messaging or policy?

I can’t speak to messaging.

If it’s a policy discussion, everything is complicated by the fact that, however much Democrats may want to help rural communities (and in general, I think their policy preferences right now do seek to help them. No doubt they could do better.), they face two tremendous obstacles.

One, Republicans vigorously obstructed the entire Democratic agenda during Obama’s administration, and paid no discernible long-term electoral price for breaking longstanding democratic norms to do so. And there is no evidence that they ever will in the future. [To clarify, if the economy crashes under a GOP president, I assume there will be consequences. But the evidence seems to be that the GOP can engage in maximal procedural sabotage during Democratic administrations (infinite filibusters, debt-ceiling hostage taking, shutdowns, etc.) and will pay effectively no significant price for it. Ever. It would be foolish.]

And two, related to this, is the fact the media is totally uninterested, if not totally incapable, of discussing policy differences in any intelligent way, much less evaluating their objective outcomes.

This is a great post, Boo. I agree with it and I admire the way it is put together.

I also want to second what Keir is saying. Despite decades of brainwashing from the right, and little help from the left, there are many people, all over the country, who would vote for Democrats if the Democrats would actually give them something to vote for. And if the message could reach them, which with today’s right-wing monopoly of communications, represents a critical problem.

Above all, we have to break through this idea that you are privileged by the very fact of being white. There are differences, for sure, in how whites and non-whites are treated in this country, but for masses of downwardly-mobile whites, these differences do not translate into anything they could recognize as “privilege”.

Race, gender, and class are ALL factors that have to be considered in equalizing opportunity. Democratic Party discourse on social justice pays a lot of attention to race and gender, but more and more just ignores class. And people whose disadvantages are due more to class than race or gender don’t understand that and they resent it. And they are not wrong to do so.

For example, we know that PoC are discriminated against in housing. But it’s mostly non-wealthy and poor PoC you’re talking about when you say this. And conversely, during the mortgage meltdown, yes, a lot of people who lost their homes were PoC, but

“The Center for Responsible Lending (CRL) recently published numerous research reports that show African Americans and Latinos receive a disproportionate share of subprime loans, even when they have similar credit scores to non-Hispanic White borrowers. In December 2007, CRL issued a report showing how subprime home loans are resulting in a devastating epidemic of foreclosures.

Despite overwhelming evidence that support the above findings, this report reveals that the majority of subprime rate loans originated in 2006 were granted to non-Hispanic Whites and upper income borrowers. The same pattern occurred in 2005. In 2004, more subprime rate loans were originated for non-Hispanic Whites, but middle-income

borrowers had the highest share. These findings are contrary to the way subprime rate lending is commonly portrayed. Popular media myths and erroneous assumptions about subprime rate loans are continuously presented as if subprime rate lending was predominately in the domain of minorities and low-income borrowers.”

http://www.compliancetech.com/files/Demographic%20Impact%20of%20the%20Subprime%20Mortgage%20Meltdown

.pdf

This election is a wake up call, a very late one, telling us we can’t afford this any longer, because it creates a gigantic blind spot and distorts our thinking.

This is what not only Webb, but also ELizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and many others have been trying to tell us. As Arthuir Gilroy says, Wake the fuck up.

Predatory lending is an issue that can win for Dems and for persons of integrity. Here in SD, in the 2016 election, a cap of interest rates for predatory lenders was put on the ballot by citizen initiative. It capped the interest rates at 36%, which seems high, but normal short-term loan interest rates are much higher on an APR basis.

The predatory lenders fought back. They put a competing issue on the ballot, which capped interest rates at 18%, but the cap was waivable – you could agree that the cap not be imposed. In other words, it was meaningless.

The people of SD voted in favor of the 36% cap by 75-25. They voted against the bad cap 75-25.

This was a bipartisan reform.

It’s a bright spot. I hope the R legislature does not weaken it.

Another good discussion of rural issues.

In 2012, I ran for State Senate in SD in a specific district. You can probably figure out who I am by naming the district, so I won’t. Suffice it to say that it is a district partially in Sioux Falls and partially in close “suburbs” of Sioux Falls.

Like all but 3 of the 35 state districts in SD, the district is R. It is R+2 or R+3, meaning that of the 14000 or so resident, I would need to get about 1000 more to vote for me than are registered – either R voting for me or I voting.

Easy, right?

I started on Labor Day. I used the Voter data base from the SD dem party. It provides a “partisan score” for each resident of the district, house by house. You can filter it. I filtered it, as suggested for “independents and mixed houses”. That got me to about 3500 houses. By hitting 200/day for the month of September, I pretty much did those houses.

I would go to a block and hit one of 20 houses. I didn’t do the rest.

Mostly I was received neutrally. I pushed the teachers, who are underpaid. That was my issue. I got some pretty serious pushback from some about that.

After I finished my list, I then took my neighborhood, and went door to door to hit everyone. That’s how I ended up in the argument with the NRA guy.

At the end, I got 47%, my opponent, a well known pol who might be gov in 10 years, got 53%.

So, when you say “Oh, we only need to get 50,000 votes”, to me that is the moon. It is very hard to get those votes. VERY HARD. Getting people to switch parties is NOT EASY. Please do not assume that it is easy.

It is turnout and the few undecideds.

And, in case you are interested, I paid mostly out of my own pocket for this little exercise. It cost about 4500 for signs, postage for postcards, etc. I got nothing from the SD Dem party. Parties do not support candidates usually. The Party chair said “You are not going into debt for this campaign are you?” I assured him that I would not.

One deep psychological theory explains Trump’s win very plainly – Graves Value Systems. The Values are deep judgement principles that dictate personal reality, beliefs, behaviors.

The Graves theory was inspired by Maslow’s pyramid of needs. I had briefly explained it in other blog.

The odd-numbered Value Systems are individualistic: 1 – Basis Survival; 3 – Authoritarian; 5 and 7 – Entrepreneurial, with 7 flexibly aware of other value systems; 9 – Transhumanism (rather speculatively).

The even-numbered Values Systems are communal: 2 – Tribal; 4 – Traditional-religious; 6 – Progressive; 8 – Ecological.

In terms of that, Clinton clearly assumes Level 6 of educated liberals. Hurtfully, she was not curious, aware of other Value Systems. Anyone who did not subscribe to her Values was a “deplorable” racist, misogynist, etc. Or so it seems.

But with harder economic times, acceptance of higher Value Levels (particularly of 6) is on decline, especially in rural and blighting areas. Not understanding, acknowledging other Values is a big fail.

Trump surely addressed Autocratic Level 3 straight on, and had little competition for Traditional-religious Level 4, Tribal Level 2, economic interests of Entrepreneurial Levels 5 and 7.

Absolutely right! Again, Rhetoric 101: Fundamental principles of communication, education, persuasion.

To connect to the other Values – absolutely!

You have to connect with audience values if you want to communicate.

That’s what this guy is saying too …