Last Wednesday, a derecho ripped through Pennsylvania knocking down trees with the force and suddenness of a bowling ball. My power went out within a seconds of the front arriving, and it remained out until Sunday evening–a total of 105 hours. This forced me to be economical with my internet use, since my only link was the data-limited hotspot feature on my phone, and my only charger was my car.

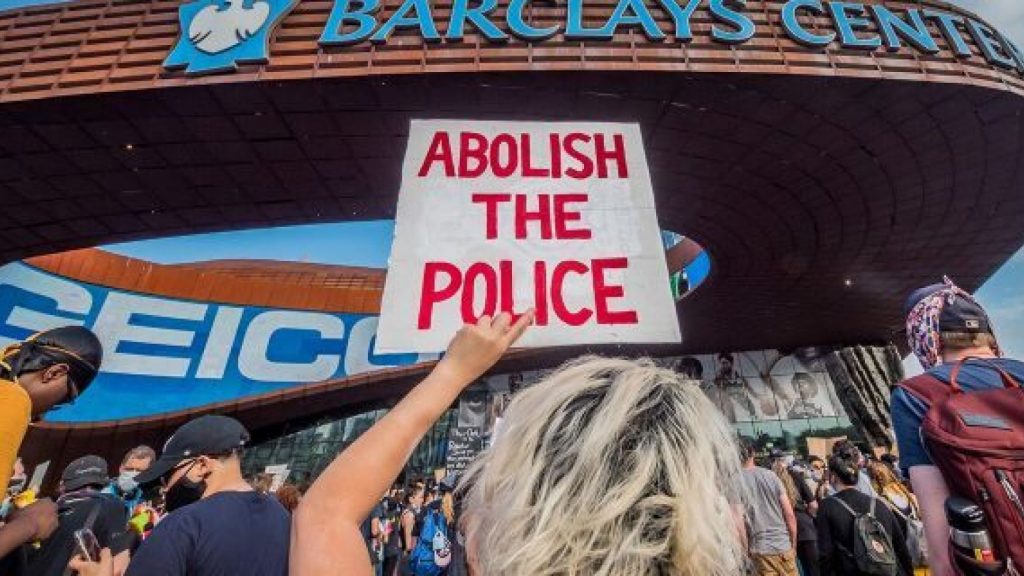

Nonetheless, I was able to follow the stunning cascade of cultural transformation stemming from the nationwide protests against police brutality. A week that started with the president flexing his muscles amidst widespread concern about looting, ended with growing calls to defund and abolish metropolitan police forces. Along the way, the public witnessed one viral video after another of police using riot control weapons against peaceful protestors, blinding one reporter with a rubber bullet, killing an asthmatic women with tear gas, pushing on old man to the street and causing blood to gush from his head. As the mood of the country changed, New York Times opinion page editor James Bennett was forced to resign after publishing a piece by Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas that called for using the military against American citizens. NFL players elicited an apology from the league commissioner for the way the league had dismissed and punished protests against police violence. The Pentagon revolted against Trump and demobilized active duty and National Guard forces that had been deployed to the capital.

By Sunday, the pendulum had swung so far against the police that liberal friends of mine began texting me in a kind of panic. What set them off was a decision by the Minneapolis city council to disband their police department:

Less than two weeks since the killing of George Floyd, 9 of the 12 members of the Minneapolis City Council — a veto-poof majority — have pledged to disband the Minneapolis Police Department. “Decades of police reform efforts have proved that the Minneapolis Police Department cannot be reformed and will never be accountable for its actions,” the group announced at a rally on Sunday. “We are here today to begin the process of ending the Minneapolis Police Department and creating a new, transformative model for cultivating safety in Minneapolis.”

Council president Lisa Bender spoke for the group in saying, “Our commitment is to end our city’s toxic relationship with the Minneapolis Police Department. It is clear that our system of policing is not keeping our communities safe. Our efforts at incremental reform have failed, period.”

To my concerned friends, this sounded like the kind of liberal overreach that Republicans have historically eaten for lunch: “This is great, we’ll just ask the people to police our cities and Joe Biden will be destroyed in the election.”

As Scottie Andrew of CNN explains, there is indeed an intellectual movement to do something this radical.

The solution to police brutality and racial inequalities in policing is simple, supporters say: Just defund police.

It’s as straightforward as it sounds: Instead of funding a police department, a sizable chunk of a city’s budget is invested in communities, especially marginalized ones where much of the policing occurs.

The concept’s been a murmur for years, particularly following the protests against police brutality in Ferguson, Missouri, though it seemed improbable in 2014.

But it’s becoming a shout.

So far, there aren’t many examples of people putting these ideas into action. Yet, it should be acknowledged that reforming the nation’s metro police forces is largely a problem for Democrats to solve. Most of the horrifying viral videos we’ve witnessed over the last week have been filmed in Democratically-run cities–not only Minneapolis, but Seattle, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Philadelphia and New York.

One possible template is Camden, New Jersey, which actually disbanded its entire police force in 2013. They fired everyone and set up a countywide police force. They went from 87 murders per 100,000 residents in 2012 to 22 total murders in 2018. This at least showed that it’s possible to cashier an entire metro force without it resulting in carnage, but it’s not necessarily a great example of what needs to be done now.

One of the motivations for disbanding the Camden police force was to bust their union. While the countywide force is still unionized, they enjoy much lower pay and less generous benefits. Busting police unions may be a prerequisite to installing systems of effective accountability, but the idea shouldn’t be about compensating cops less for doing the same jobs. Another problem is that Camden did not use the opportunity to diversify their police force. Most of the new recruits were white and had never lived a day within the city’s borders. Partially for this reason, the city rehired many of the veterans of the city force and used them to mentor the newbies.

Many of the newly minted officers are young recruits with either no prior or only part-time experience, a top concern for some local residents. To get them up to speed, the department has turned to its veteran officers. “The former city police officers who came over were the most important part of the puzzle with indoctrinating the new officers to the city, the neighborhoods and policing,” Chief [Scott] Thomson says. Newly certified officers attend a regional police academy and complete another eight weeks of field training to prepare for the challenging environment Camden poses. “Until you’re actually there doing it on a day-to-day basis, it’s hard to wrap your head around it,” says Sgt. Kevin Lutz, who trains recruits at the academy. “We do our best to explain to them the different experiences we’ve had in the past, and try and really get them prepared for what they’re about to do.”

This seems totally contrary to what people want to achieve right now, which is a complete cultural rethinking of how we go about policing our cities.

What Camden did was not unprecedented: “Las Vegas merged its police department with the Clark County Sheriff’s Department in 1973; the city of Charlotte, N.C., joined forces with surrounding Mecklenburg County in 1993.” But this kind of arrangement is only possible in jurisdictions where the county is not synonymous with the city. It wouldn’t work in Philadelphia, for example.

Yet, even if Camden cannot serve as a perfect template for other cities to follow, its experience shows that radical change is possible and won’t necessarily put people at increased risk during the transitional period. You really can fire every last member of a metro police force and get away with it.

Joe Biden isn’t going to embrace rhetoric about “defunding the police,” let alone “abolishing” them. But he can embrace rethinking them. There’s clearly a pervasive, countrywide cultural problem with our metro police forces and it percolates down to smaller forces, too. Ripping them up and starting over is probably desirable wherever it can be achieved, as it’s clearly not enough to just train the police to be nicer. You have to worry about losing experience in the bargain, but a lot of that experience is in brutalizing the citizens they’re supposed to serve and protect. If the baby is what polluted the bathwater in the first place, then throwing them both out is less of a concern, and maybe even the main point. You definitely don’t want to rehire the baby to train the new force.

I told my worried progressive friends that they shouldn’t worry so much. FDR really benefited from having the example of Huey Long calling for much more radical and threatening reforms. It’s not a bad thing to have people clamoring for unrealistic or even politically untenable reforms if it makes you look like a reasonable alternative and carves out more space to enact transformative change.