It’s unfortunate that it took an apocalyptic sexual abuse scandal to inspire me to look deeply into the political power structure of the Southern Baptist Church. I quickly learned some really important history that had somehow escaped my notice. For example, I did not know about the importance of New Orleans’ Café Du Monde in the “creation story” of the conservative takeover of the church’s hierarchy.

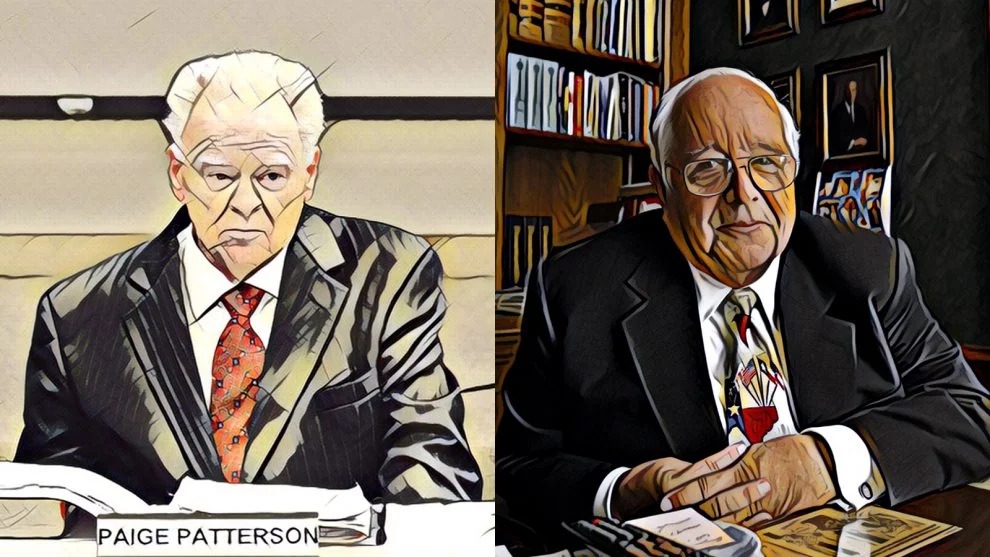

Those outside the SBC world cannot imagine the power of the mythology of the Café Du Monde—the spot in the French Quarter of New Orleans where [in 1967], over beignets and coffee, two men, Paige Patterson and Paul Pressler, mapped out on a napkin how the convention could restore a commitment to the truth of the Bible and to faithfulness to its confessional documents.

For Southern Baptists of a certain age, this story is the equivalent of the Wittenberg door for Lutherans or Aldersgate Street for Methodists. The convention was saved from liberalism by the courage of these two men who wouldn’t back down, we believed.

In 2005, Albert Mohler, who was then serving as the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote a review of an essay written by Paige Patterson called Anatomy of a Reformation: The Southern Baptist Convention 1978-2004. In detailing Patterson’s motivation in 1967 for initiating a conservative reformation within the church, Mohler explained the centrality of biblical literalism.

An early signal of coming controversy was issued by Houston pastor K. Owen White, who as president-elect of the Southern Baptist Convention directed his attention at a recent book written by a professor at one of the Southern Baptist Convention’s six seminaries. Ralph Elliott, a professor of Old Testament at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, had written The Message of Genesis, a book that had been published by the denomination’s official press. As Patterson explains, the book “had employed historical-critical assumptions, conclusions, and methodologies, which led the professor to question the historicity of some of the narrative portions of Genesis.”

As an observant college student, Patterson was surprised that his Baptist religion professors supported Elliott and dismissed White’s concerns.

The actual conservative takeover of the church is usually dated to 1978, so it took a little over a decade for the plan hatched at the Café Du Monde to come to fruition. The driving force for the coup was a desire to stamp out any doubt about the inerrancy of the Bible. Another way of putting it is that Patterson and Pressler understood that they could seize control of the Southern Baptist Executive Committee and use it as a kind of protestant Inquisition to enforce orthodoxy within the denomination.

But the Southern Baptist church is completely unlike the Catholic Church. Orders from on high do not carry the same weight with Southern Baptists and what control exists has to be exercised in a careful dance related to the “Cooperative Program.”

Southern Baptist churches are all technically independent and don’t answer to anyone. But to be formally recognized they need to donate money to the Cooperative Program which is then used to fund missionary work. This is all directed by the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee, and it’s in their interest to collect as much revenue as possible. That presents a disincentive to discipline pastors or disown congregations.

But a disincentive is not the same as an impossibility. In recent years, the Executive Committee has taken some strong stands.

Critics have said that the Southern Baptist Convention is comfortable drawing hard lines from the top down when it chooses. After one of the denomination’s largest congregations, Saddleback Church in Southern California, announced it had ordained three women pastors in supporting roles last year, high-profile pastors and leaders criticized the church sharply, and a committee was assigned to examine whether the denomination should break with the church.

Last year, the Southern Baptist Convention’s executive committee expelled two churches over their decisions to accept gay couples as members and church policies that the denomination deemed accepting of homosexuality.

As you can see, if the Executive Committee is willing to forego revenue, it can expel congregations from the Church. But, for decades, they used the decentralized and voluntary structure of the denomination as an excuse for why the could do nothing about sexual predators in positions of leadership. An independent report ordered by church laity on the breadth of the sexual abuse problem dropped this week, and the strong reaction indicates that many people aren’t buying the decentralized excuse.

To play Devil’s Advocate for a moment, it’s true that it would have been tricky for the Executive Committee to do what people are saying they should have done. They aren’t responsible for hiring pastors or placing them in congregations. Unlike the Catholic Church, they didn’t move accused priests to new unsuspecting parishes where they could continue their predations. In order to protect the flock from sexual abusers, the Executive Committee would have had to monitor complaints from many hundreds of churches and then develop some kind of coercive standard to assure that offenders were removed from power and could not find employment elsewhere.

The impracticality of this was used as an excuse for doing nothing at all. But, it turns out that they actually did take one important step in the right direction. They built a database to collect reports of sexual abuse. The problem is that they kept it a secret and used it solely to protect themselves from potential legal liability. The one constant is that financial concerns trumped any concern about victims.

According to former policy head of the Executive Committee Russell Moore, both Patterson and Pressley are in disrepute now.

Those two mythical leaders are now disgraced. One was fired after alleged mishandling a rape victim’s report in an institution he led after he was documented making public comments about the physical appearance of teenage girls and his counsel to women physically abused by their husbands. The other is now in civil proceedings about allegations of the rape of young men.

We were told they wanted to conserve the old time religion. What they wanted was to conquer their enemies and to make stained-glass windows [link] honoring themselves—no matter who was hurt along the way.

Because the Cooperative Program is both the missionary arm of the Southern Baptist Convention and it’s mechanism of control and theological enforcement, it was possible to argue that goal of spreading the Gospel would be undermined if participants were expelled or alienated through investigations of sexual misconduct. On the one hand, this was a convenient excuse, but on the other it was true that the arrangement was ill-suited for the job. One problem was that there was simply so much sexual misconduct. This is clear by looking only at those who have been found guilty of sex crimes. When we consider those who haven’t yet faced justice, the numbers are staggering.

In some quarters, pastors and church members are openly frustrated at what they see as years of inaction on a crisis that has publicly persisted since 2019, when an investigation by The Houston Chronicle and The San Antonio Express-News revealed that nearly 400 Southern Baptist leaders, from youth pastors to top ministers, had pleaded guilty or been convicted of sex crimes against more than 700 victims since 1998.

To get their hands around a problem that big, the Executive Committee would have had to create a full-time bureaucracy staffed by dozens of employees. The problem here is that we have a mismatch between the power the Executive Committee wants to exert in some fields and the way it is able to exert that power to obtain compliance.

The whole point of the conservative reformation was to stamp out heterodoxy using the voluntary Cooperative Program as the mechanism of control. This made the church hierarchy dependent on the Cooperative Program and also mindful that it needed to choose its battles carefully. If they made decisions that caused a decrease in participation, they’d lose both revenue and control. Part of the dance was to coerce while giving the congregations the sense of their own independence.

On some things, like making an example of congregations that embraced gay rights, they felt they could take a hard stand on not get punished. But as for creating a nationwide sexual predator monitoring system, they felt this would open a can of worms that would unravel the whole system. They’d rather quickly find that taking responsibility for the hiring practices of hundreds of congregations and using the Cooperative Program as their mechanism of enforcement, would invite backlash and reduce participation.

So, they strongly resisted taking that approach and the result was catastrophic.

Many of them even convinced themselves that the controversy was the work of the Devil–a devious way to undermine their efforts to evangelize the Gospel to the world. But, in a real way, the problem was built into the structure. Southern Baptists really have to choose between two things. They can maintain the fierce independence of their congregations or they can grant power to some distant church hierarchy.

What they can’t do is have it both ways. They can’t stamp out all heterodoxy within the Church and still have fully independent congregations. They tried this, and they got the worst of both worlds.

A real reformation within the Church would see congregations find a new way to fund their missionary work. As for dealing with sexual predators, rather than relying on some giant centralized bureaucracy, they might join with other faiths and denominations in creating some kind of crowdsourced database so offenders can’t easily relocate and find new congregations to victimize.

Finally, I’ll just note that any religious movement based on the inerrancy of the ancient scriptures is bound to run into severe problems. That becomes clear the second you ponder who has the power to exert the thought control and the mechanisms they’ll need to do the job.