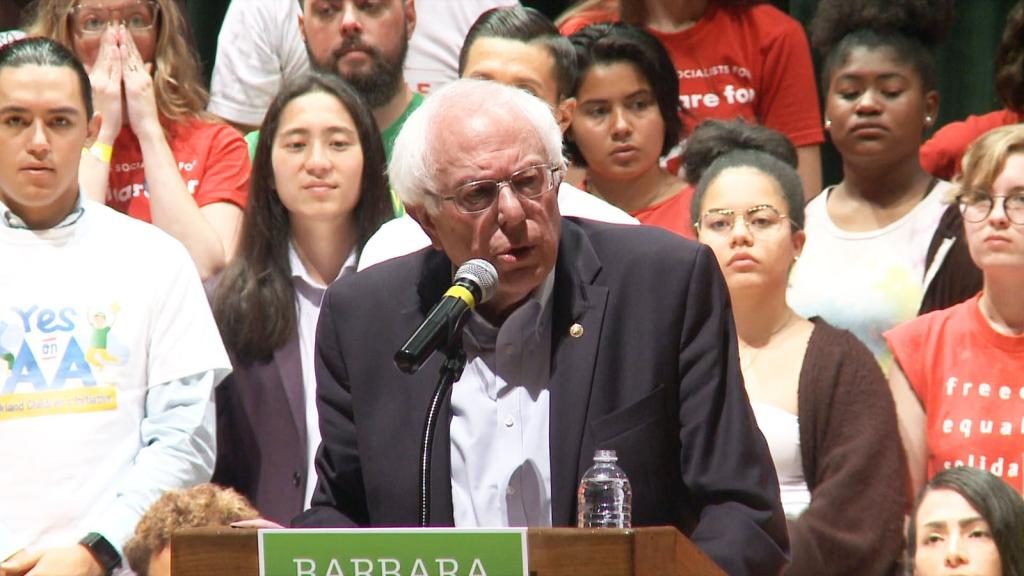

Image Credits: CSPAN.

A new study of non-voters by the Knight Foundation confirms everything I thought I knew about the prospects for winning a presidential election through heightened voter mobilization. Whatever the intrinsic merits of increased civic participation, as an electoral strategy for the Democrats against Donald Trump, it is highly dubious.

The report examined 12,000 “chronic non-voters in America, across the country and in key battleground states.” Their bottom line finding is that if all these people went to the polls, the Democrats would increase their popular voter margin and lose the Electoral College even more decisively than in 2016.

Of all the battleground states, my home base of Pennsylvania had the worst numbers. Trump leads here with non-voters by a 36 percent to 28 percent margin. This is consistent with my impression that most of the untapped vote in the Keystone State is composed of white voters who have little to no higher education. A similar situation holds for Virginia, Florida and Arizona, Of the nine battleground states where they questioned non-voters, only Georgia showed an advantage for a generic Democrat over Trump that is outside of the survey’s margin of error.

Another suspicion of mine was confirmed, too, which is that Bernie Sanders would fare best among this group largely because he’s not perceived as a typical Democrat and his calls for systemic change match the sentiments of non-voters. It’s this sentiment that explains why Trump does so well with this group, and it’s also why more conventional politicians, like Hillary Clinton or Mitt Romney, have little appeal to them.

In [Meagan] Day’s estimation, Bernie Sanders, like Trump, is appealing to people who don’t typically vote because he has managed to put some distance between himself and the Democratic Party establishment. “There are a lot of people who like Donald Trump who don’t necessarily love the Republicans,” she notes. “When we look at who doesn’t vote, we’re looking at people who are feeling alienated from the political process because they feel like there’s nothing on offer from them from either party. And they don’t get the sense that anybody wants to fight for them.”

…In a New York Times survey of swing state nonvoters, Sanders was the most popular Democrat, besting Trump by 4 percentage points, while Warren was actually 1 point less popular than Trump among nonvoters. The same survey showed that between Democratic voters and nonvoters who favor Democrats, fewer nonvoters consider themselves “very liberal” or say they want a candidate who “promises to fight for a bold progressive agenda,” but more nonvoters than voting Democrats want a candidate who “will fundamentally change America.” The Times survey also showed that more Democratic-leaning nonvoters than Democratic voters in swing states support single-payer health care.

Armed with this data, perhaps it is easier to understand my point of view. Winning Pennsylvania appears to be a prerequisite for a Democrat hoping to defeat Trump. Bernie Sanders is using an approach that intuitively makes no sense in Pennsylvania, which is to trust in mobilizing low-proclivity voters to the polls using a populist approach that will hurt his performance badly in the suburbs where Democrats have been surging massively over the last four years. In general, low proclivity voters in Pennsylvania heavily favor Trump, so higher turnout is not going to help a generic Democrat.

Yet, Sanders is not a generic Democrat. And, for this reason, he might be able to win here using this approach while other Democrats would fail. Perhaps his best argument is that this election will have historically high turnout, and he’s best positioned to compete for those votes in Pennsylvania.

But that’s highly speculative and tremendously risky. It’s also not something most Pennsylvania Democrats want to try because even if it were to succeed for Sanders it might not be a success for them. This is what I tried to explain in my piece: Bernie’s Coalition Doesn’t Overlap With Dem’s House Majority. The short version is that the Democrats have recently won scores of federal, state, and local races in the suburbs and those seats could be at risk if the top of the ticket underperforms. The shape of the electorate matters a lot, as we know from watching Clinton win the popular vote and lose the election.

But Clinton actually lost the popular vote in Pennsylvania, which is why I began arguing immediately after the election that the Democrats needed to get away from a strategy that relied solely on the suburbs and win back some support in rural areas and small towns. Sanders would create a test-case for that, but it’s really flying in the face of all the momentum the Democrats have made using the suburban approach.

A simple way of putting this is that Donald Trump has more say in how the country is polarized than any challenger could ever have. His policies and behaviors have pushed suburbanites away from the GOP and given the Democrats a House majority based on their support. They need to protect that majority, and the new officeholders certainly prefer a strategy premised on winning over rather than alienating their constituents.

I’d prefer a left-wing coalition that is more in the FDR mold of representing working people first and foremost. The country club folks could go back to complaining about how the unwashed are getting more than their fair share rather than constituting the backbone of the Democratic majority. But Trump doesn’t really allow this shape to take form, and the Democrats would be foolish to toss away easy seats in a theoretical effort to win difficult ones.

Those who believe in Sanders, trust that he can pull off a win by mobilizing non-voters. They’re probably right that he’s the only Democrat running who has a chance at victory with this approach, But non-voters in battleground states are currently leaning to Trump, so this strategy looks perilous and it has a serious downside.

The downside is that a lot of Democratic officeholders do not see the strategy as serving their self-interest, which means many of them will reject it or try to keep their distance. The cost comes in lack of party unity. And it’s hard to measure how lack of unity might impact the campaign.

There is no absolutely safe strategy. The Democrats could nominate a more mainstream candidate who is broadly liked in the suburbs and discover that way too many Trump-leaning non-voters turn out in November and swamp them at the polls. But this strategy would keep the party more united and that counts for a lot.

None of this is really that complicated. If the Democrats nominate a candidate who is not actually a Democrat, they’ll be splintered as a party but probably have more appeal to folks who don’t really like Democrats (or Republicans) in the first place.

I guess my biggest worry is that I have doubts about any strategy that depends on people doing what they have not done in the past. I have too much experience with people who suffer from addiction to believe that this is often a winning bet.