Crossposted from Left Toon Lane, Bilerico Project & My Left Wing

click to enlarge

From Wikipedia:

As W.E.B. DuBois noted, “It is always difficult to stop war, and doubly difficult to stop civil war… In the case of civil war, where the contending parties must rest face to face after peace, there can be no quick and perfect peace.” As reported by Mississippi Governor Sharkey in 1866, disorder, lack of control and lawlessness were widespread; in some states armed bands of Confederate soldiers roamed at will. Southerners seemed to take out on blacks all their wrath at the Federal government. They casually attacked and killed blacks whose bodies were left on the roads.

The original Ku Klux Klan was created in the aftermath of the American Civil War by six educated, middle-class Confederate veterans on December 24, 1865. from Pulaski, Tennessee. They made up the name by combining the Greek “kyklos” with “clan” It was one among a number of secret, oath-bound organizations, including the Southern Cross in New Orleans (1865), and the Knights of the White Camellia.

In an 1867 meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, Klan members gathered to try to create a hierarchical organization with local chapters reporting eventually up to national headquarters. As most of them were veterans, they were used to such organization. Former Confederate Brigadier General George Gordon put the proposals together in what was called the “Prescript.” The Prescript suggested elements of white supremacy belief. For instance, an applicant should be asked if he was in favor of “a white man’s government”, “the reenfranchisement and emancipation of the white men of the South, and the restitution of the Southern people to all their rights.” Despite Gordon’s work, local Klan units never accepted the Prescript and continued to operate autonomously. There were never hierarchical levels or state headquarters.

Gordon supposedly told former slave trader and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in Memphis, Tennessee, about the Klan. Forrest allegedly responded, “That’s a good thing; that’s a damn good thing. We can use that to keep the niggers in their place.” A few weeks later, Forrest was selected as Imperial Wizard, the Klan’s national leader, though he always denied leadership.

In effect, the Klan defended the interest of the planter class and Democratic Party by working to curb the education, economic advancement, voting rights, and right to keep and bear arms of blacks. The Ku Klux Klan soon spread into nearly every southern state, launching a “reign of terror” against Republican leaders both black and white. Those political leaders assassinated during the campaign included Arkansas Congressman James M. Hinds, three members of the South Carolina legislature, and several men who served in constitutional conventions.”

In an 1868 newspaper interview, Forrest stated the Klan’s primary opposition was to the Loyal Leagues, Republican state governments, people like Tennessee governor Brownlow and other carpetbaggers and scalawags. He claimed that many southerners believed blacks were voting for the Republican Party because they were being hoodwinked by the Loyal Leagues. One Alabama newspaper editor declared “The League is nothing more than a nigger Ku Klux Klan.” At the local level, however, old feuds and grudges were the cause of numerous attacks, and Klan members worked for their own dominance in the disrupted postwar society.

As historian Elaine Frantz Parsons discovered:

Lifting the Klan mask revealed a chaotic multitude of antiblack vigilante groups, disgruntled poor white farmers, wartime guerrilla bands, displaced Democratic politicians, illegal whiskey distillers, coercive moral reformers, sadists, rapists, white workmen fearful of black competition, employers trying to enforce labor discipline, common thieves, neighbors with decades-old grudges, and even a few freedmen and white Republicans who allied with Democratic whites or had criminal agendas of their own. Indeed, all they had in common, besides being overwhelmingly white, southern, and Democratic, was that they called themselves, or were called, Klansmen.

As historian Eric Foner observed…

In effect, the Klan was a military force serving the interests of the Democratic party, the planter class, and all those who desired restoration of white supremacy. Its purposes were political, but political in the broadest sense, for it sought to affect power relations, both public and private, throughout Southern society. It aimed to reverse the interlocking changes sweeping over the South during Reconstruction: to destroy the Republican party’s infrastructure, undermine the Reconstruction state, reestablish control of the black labor force, and restore racial subordination in every aspect of Southern life.

Klan members adopted masks and robes that hid their identities and added to the drama of their night rides, their chosen time for attacks. Many of them operated in small towns and rural areas where people otherwise knew each other’s faces, and sometimes still recognized the attackers. “The kind of thing that men are afraid or ashamed to do openly, and by day, they accomplish secretly, masked, and at night.” With this method both the high and the low could be attacked. The Ku Klux Klan night riders “sometimes claimed to be ghosts of Confederate soldiers so, as they claimed, to frighten superstitious blacks. Few freedmen took such nonsense seriously.”

The Klan raided black members of the Loyal Leagues and intimidated southern Republicans and Freedmen’s Bureau workers. When they killed black political leaders, they also took heads of families, leaders in churches and community groups, because people had many roles. Agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau reported weekly assaults and murders of blacks. “Armed guerilla warfare killed thousands of Negroes; political riots were staged; their causes or occasions were always obscure, their results always certain: ten to one hundred times as many Negroes were killed as whites.” Masked men shot into houses and burned them, sometimes with the occupants still inside. They drove successful black farmers off their land. General Canby reported that in North and South Carolina, in 18 months ending in June 1867, there were 197 murders and 548 cases of aggravated assault.

Klan violence worked to suppress black voting. As examples, over 2,000 persons were killed, wounded and otherwise injured in Louisiana within a few weeks prior to the Presidential election of November 1868. Although St. Landry Parish had a registered Republican majority of 1,071, after the murders, no Republicans voted in the fall elections. White Democrats cast the full vote of the parish for Grant’s opponent. The KKK killed and wounded more than 200 black Republicans, hunting and chasing them through the woods. Thirteen captives were taken from jail and shot; a half-buried pile of 25 bodies was found in the woods. The KKK made people vote Democratic and gave them certificates of the fact.

In the April 1868 Georgia gubernatorial election, Columbia County cast 1,222 votes for Republican Rufus Bullock. By the November presidential election, however, Klan intimidation led to suppression of the Republican vote and only one person voted for Ulysses S. Grant.

Klansmen killed more than 150 African Americans in a county in Florida, and hundreds more in other counties. Freedmen’s Bureau records provided a detailed recounting of beatings and murders of freedmen and their white allies by Klansmen.

Milder encounters also occurred. In Mississippi, according to the Congressional inquiry:

One of these teachers (Miss Allen of Illinois), whose school was at Cotton Gin Port in Monroe County, was visited … between one and two o’clock in the morning on March 1871, by about fifty men mounted and disguised. Each man wore a long white robe and his face was covered by a loose mask with scarlet stripes. She was ordered to get up and dress which she did at once and then admitted to her room the captain and lieutenant who in addition to the usual disguise had long horns on their heads and a sort of device in front. The lieutenant had a pistol in his hand and he and the captain sat down while eight or ten men stood inside the door and the porch was full. They treated her “gentlemanly and quietly” but complained of the heavy school-tax, said she must stop teaching and go away and warned her that they never gave a second notice. She heeded the warning and left the county.

By 1868, two years after the Klan’s creation, its activity was beginning to decrease. Members were hiding behind Klan masks and robes as a way to avoid prosecution for free-lance violence. Many influential southern Democrats feared that Klan lawlessness provided an excuse for the federal government to retain its power over the South, and they began to turn against it. There were outlandish claims made, such as Georgian B.H. Hill stating “that some of these outrages were actually perpetrated by the political friends of the parties slain.”

Although Forrest boasted the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men and he could muster 40,000 Klansmen with five days’ notice, as a secret or “invisible” group, it had no membership rosters, no chapters, no local officers, making it difficult for observers to judge its membership. It had created a sensation by the dramatic nature of its masked forays and many murders.

One Klan official complained his, “so-called ‘Chief’-ship was purely nominal, I having not the least authority over the reckless young country boys who were most active in ‘night-riding,’ whipping, etc., all of which was outside of the intent and constitution of the Klan…”

A federal grand jury in 1869 determined the Klan was a “terrorist organization.” It issued hundreds of indictments for crimes of violence and terrorism. Klan members were prosecuted, and many fled jurisdiction, particularly in South Carolina. Many people not formally inducted into the Klan had used the Klan’s uniform for anonymity, to hide their identities when carrying out acts of violence. Forrest ordered the Klan to disband in 1869, stating it was “being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace.” Historian Stanley Horn writes “generally speaking, the Klan’s end was more in the form of spotty, slow, and gradual disintegration than a formal and decisive disbandment.” A reporter in Georgia wrote in January 1870, “A true statement of the case is not that the Ku Klux are an organized band of licensed criminals, but that men who commit crimes call themselves Ku Klux.”

While people used the Klan as a mask for nonpolitical crimes, state and local governments seldom acted against them. African Americans were kept off juries. In lynching cases, all-white juries almost never indicted Ku Klux Klan members. When there was a rare indictment, juries were unlikely to vote for conviction. In part, jury members feared reprisals from local Klansmen.

Others may have agreed with lynching as a way of keeping dominance over black men. In many states, officials were reluctant to use black militia against the Klan from fear that race tensions would be raised.When Republican Governor of North Carolina William Woods Holden called out the militia against the Klan in 1870, it added to his unpopularity. Combined with violence and fraud at the polls, in the election, the Republicans lost their majority in the state legislature. Disaffection with Holden’s actions led to white Democratic legislators’ impeaching Holden and removing him from office, but their reasons were numerous.

Union Army veterans in mountainous Blount County, Alabama, organized ‘the anti-Ku Klux.’ They put an end to violence by threatening Klansmen with reprisals unless they stopped whipping Unionists and burning black churches and schools. Armed blacks formed their own defense in Bennettsville, South Carolina and patrolled the streets to protect their homes.

National sentiment gathered to crack down on the Klan, even though some Democrats at the national level questioned whether the Klan existed or was a creation of nervous Southern Republican governors. Many southern states began to pass anti-Klan legislation.

In January 1871, Pennsylvania Republican Senator John Scott convened a Congressional committee which took testimony from 52 witnesses about Klan atrocities. They accumulated 12 volumes of horrifying testimony. In February, former Union General and Congressman Benjamin Franklin Butler of Massachusetts introduced the Ku Klux Klan Act. This added to the enmity southern white Democrats bore toward him. While the bill was being considered, further violence in the South swung support for its passage. The Governor of South Carolina appealed for federal troops to assist his keeping control. A riot and massacre in a Meridian, Mississippi, courthouse were reported, from which a black state representative escaped only by taking to the woods.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant signed Butler’s legislation. The Ku Klux Klan Act was used by the Federal government together with the 1870 Force Act to enforce the civil rights provisions for individuals under the constitution. Under the Klan Act, Federal troops were used for enforcement, and Klansmen were prosecuted in Federal court. More African Americans served on juries in Federal court than were selected for local or state juries, so had a chance to participate in the process. In the crackdown, hundreds of Klan members were fined or imprisoned. In South Carolina, habeas corpus was suspended in nine counties. The Klan was destroyed in South Carolina and decimated throughout the rest of the South, where it had already been in decline. Attorney General Amos Tappan Ackerman led the prosecutions. “By 1872, the Klan as an organization was broken.” In some areas, other local paramilitary organizations such as the White League, Red Shirts, saber clubs, and rifle clubs continued intimidation and murder of black voters. Although destroyed, the Klan achieved many of its goals, such as suppressing suffrage for Southern blacks and driving a wedge between poor whites and blacks.

Despite suppression of the Klan, violence continued against African Americans as whites struggled for power. On Easter Sunday 1873, black citizens fought a mixed political and racial battle against white militia in Colfax, Louisiana. The ostensible cause was an election contested at both the state and local levels. Each man elected sheriff claimed the local office. When black Republicans gathered at the courthouse, white militia collected to force them to leave. Estimates of African Americans killed overnight and into the next day were 105 to 280. Some bodies were hidden in the woods or thrown in the river; others buried before state and Federal troops arrived. African-American legislator John G. Lewis remarked, “They attempted (armed self-defense) in Colfax. The result was that on Easter Sunday of 1873, when the sun went down that night, it went down on the corpses of two hundred and eighty negroes.” The Colfax Massacre had the highest fatalities of any incident of racial violence during Reconstruction.

Shortly after, in United States v. Cruikshank (1875), the Supreme Court ruled that the few convictions achieved after the Colfax Massacre were faulty. It ruled that the Force Act of 1870 did not give the Federal government power to regulate private actions, but only those by state governments. The result was that as the century went on, African Americans were at the mercy of hostile state governments to intervene against private violence and paramilitary groups.

In 1882, long after the Klan was destroyed, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Harris that the Klan Act was partially unconstitutional. It ruled that Congress’s power under the Fourteenth Amendment did not extend to regulate against private conspiracies.

As 20th century Supreme Court rulings extended Federal enforcement of citizens’ civil rights, the Force Act and the Klan Act were used by 20th c. Federal prosecutors as the basis for investigation and indictments in the 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner; and the 1965 murder of Viola Liuzzo. They were also the basis of prosecution in 1991 in Bray v. Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic.

The nadir of American race relations is often placed from the end of reconstruction to the 1910s, especially in the South. Once white Democrats regained political power in state legislatures in the 1870s, they passed bills directed at restricting voter registration by blacks and poor whites. Continued low cotton prices, agricultural depression and labor shortages in the South contributed to social tensions. According to Tuskegee Institute, the 1890s was also the peak decade for lynchings, with most of them directed against African Americans in the South. The lynchings were a byproduct of political tensions as white Democrats tried to strip blacks from voter rolls and suppress voting. Some of the violence was directed at trying to break up interracial coalitions that came to power in state legislatures in 1894, with alliances of Populist and Republican parties. In 1896 the Democrats used fraud, violence and intimidation to suppress voting by poor classes, and regained power.

From 1890 to 1908, ten of eleven southern states ratified new constitutions or amendments that completed disfranchisement of most African Americans and many poor whites. The constitutions had provisions making voter registration more complicated: such as poll taxes, residency requirements, recordkeeping, and literacy tests, which were often subjectively applied. In addition, in voting sometimes multiple ballot boxes were used. The result was that blacks and poor whites in most southern states were deprived of suffrage, representation at any level of government, local elected offices, and the right to serve on juries (usually restricted to voters). In most of the South, sweeping disfranchisement and white one-party government lasted until African Americans’ leadership and activism in the Civil Rights Movement gained passage of Federal civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965.

Beginning in 1910 and going through 1940, tens of thousands of African Americans decided to leave the South and its violence and segregation, in a movement known as the Great Migration. They went to northern and midwestern cities for jobs, better education for their children, a chance to vote, and the hopes of living with less violence. Northern industry recruited black workers because of a shortage of labor for expanding industries: for instance, the Pennsylvania Railroad hired 12,000 men, all but 2,000 of them from Florida and Georgia.

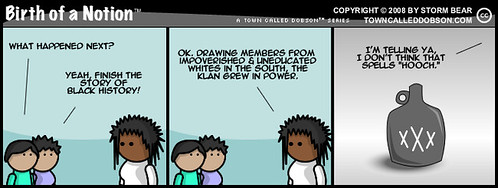

Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer & Sources

BIRTH OF A NOTION WALLPAPER is now available for your computer. Click here.