Both sides in the Brexit negotiations have been hyping the risk of a no deal Brexit and becoming more explicit in discussing the economic damage it will do. This is to be expected in the run up to the end of the negotiations, if only to soften up opponents of a deal.

“There is no alternative”, Mrs. May can be expected to say if and when negotiators finally come to a deal: The economic consequences of no deal are too awful to contemplate, a point made clear by the publication of the first of 84 studies on the economic impact of a no deal Brexit.

All of this may very well be true, particularly in the short term. But are there longer term benefits to a no deal Brexit than can overcome any short term disadvantages? This is certainly the theory which arch-Brexiteers cling to when opposing the compromises any deal would entail.

They too can be suspected of tactical maneuvering, both to stiffen the resolve of British negotiators to hold out for a better deal, and to absolve themselves of any responsibility when any final, messy, compromise deal is done.

But let us take their objections at face value, for the moment, and examine their claim that a sovereign UK, free of any entanglement with the EU, could be much more successful, economically and politically, on the world stage.

The common wisdom points to a UK in gradual decline, economically and politically, when the UK was last entirely sovereign: before it joined the EU in 1973. Since then it has lost the remains of its empire, its industrial base, and much of its influence on the world stage. Former colonies like India, Pakistan, Australia, and South Africa have become much more independent and influential.

Within the EU, on the other hand, the UK has been able to push for the rapid expansion of the EU eastwards, the creation of the Single Market and Customs Union, and the adoption of English as the working language of key EU institutions. Politically the push for Scottish independence has been contained, and the Northern Ireland troubles have been brought to an end.

What’s not to like, from a UK perspective? Apparently, rather a lot, if the Brexiteers are to be believed. Freed from meddling Brussels bureaucrats, the UK will apparently be able to negotiate much more advantageous trade deals, keep out undesirable aliens, and “take back control” over its own foreign and security policies.

“How has that been going?” The EU may well be inclined to ask, a few years from now.

First of all, it is difficult to see how the UK, a market of 65 Million people, can negotiate more advantageous trade deals than the EU with 450 Million people. It would take spectacular incompetence on the part of EU trade negotiators for that to be the case – and they have a lot of experience of negotiating trade deals, whereas the UK has none.

Secondly, immigration from within the EU has generally been of highly qualified professionals or hard working eastern Europeans prepared to do manual agricultural jobs Britons have shown little enthusiasm for doing. Their numbers have already been in decline since Brexit was announced, partly because they feel unwelcome, partly because of the decline in Sterling, and partly because their prospects elsewhere are improving with a gradual rise in EU employment levels.

Many UK farmers, employers and the NHS have been sounding the alarm that they cannot sustain output and services without these workers, who have cost the UK little to bring up, educate and train, and who generally contribute more in output and taxes than they cost in terms of the consumption of state health, education and social welfare services.

Thirdly, the UK’s foreign policies adventures in Afghanistan, Iraq, Ukraine, Libya, and Syria have not been spectacular successes of late, and Trump shows little inclination to treat the UK as anything other than a colony in future US adventurism. What has the average UK citizen to gain from all of this?

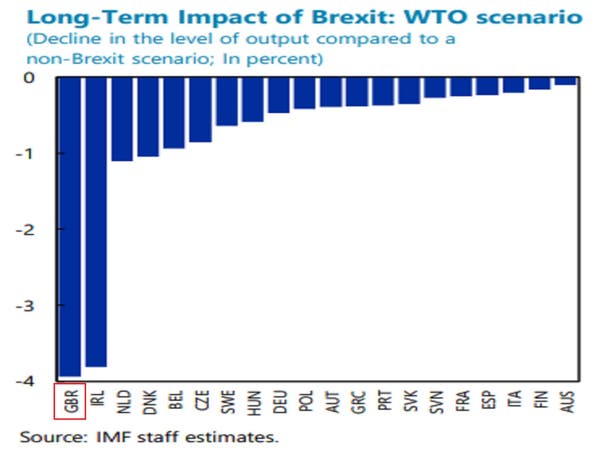

All international forecasters predict significant short/medium term economic losses for the UK, and it is difficult to see how those losses can be made good. The above chart dates from 2016, but a a recent Financial Times analysis suggests that the UK economy has already suffered a Brexit hit of between 1 and 2% of GDP.

However because the UK entered the Brexit negotiations with strong momentum, these reductions have resulted in a slowdown of UK growth relative to its G7 competitors, but not an outright recession. Record employment levels mean that the political impact has, to date, been relatively small.

All of which has meant that the UK has been able to adopt a relatively insouciant approach to the Brexit negotiations to date, up to and including a certain alacrity about the impact of a no deal Brexit if that is the outcome of the negotiations.

This is in spite of economic predictions that estimate the impact of Brexit on long term EU growth of c. 1.5% and anything from 4 to 10% on the UK. Economic predictions don’t change voter preferences, felt realities do.

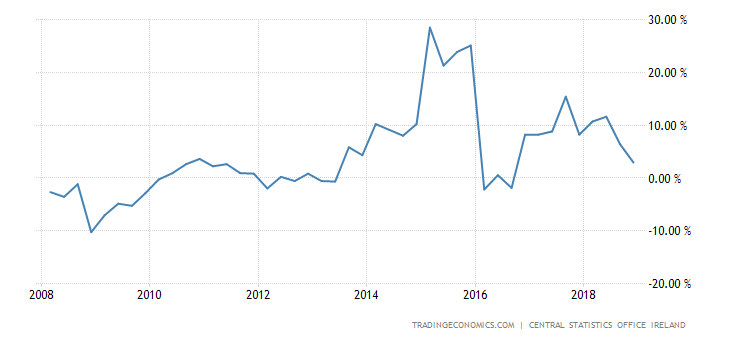

Given these are long term scenarios, spread over many years, the impact will hardly be felt in most EU countries, except for specific sectors. Ireland is the only EU country which suffers a comparable level of damage to the UK, and given Irish growth has been averaging over 5% in recent years, some cooling off may not be an entirely bad thing, even from an Irish perspective.

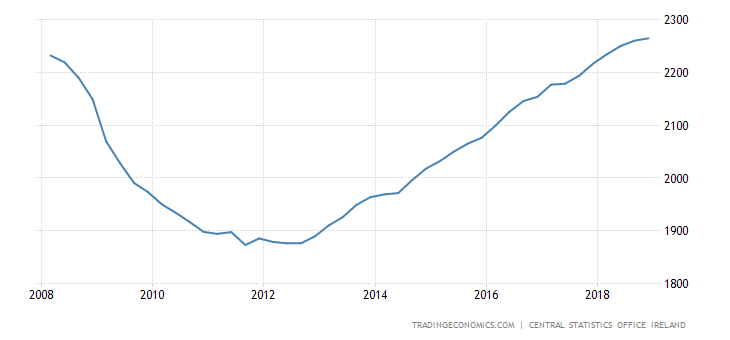

And while there is some very justified skepticism over Irish GDP figures, especially 2015/6, employment figures suggest a similar trend:

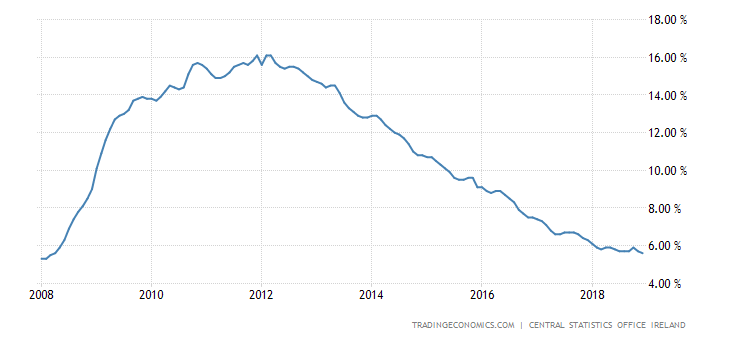

And the unemployment rate amplifies this:

So the real problem for Ireland is less the overall macro effect of a hard Brexit on the Irish economy, but on the specific impacts on our agri-food exports, subject to the highest WTO tariffs, and based in rural communities with few alternative employments. Ireland already suffers from an Urban Rural divide and gross income inequalities between Dublin and city based financial services, Big Pharma, and IT industries and more rural agri-food and service industries.

So the political impact of a hard Brexit on Ireland would be major, and that is before one factors in the impact on the Northern Ireland border and on peace and stability in N. Ireland itself. Ireland will require a special dispensation from the EU to mitigate the worst impact of Brexit and this may include a limited level of continuing free trade across the border for goods not destined for the rest of the EU.

But presuming these intra-EU issues can be managed, what has the EU really got to lose from a hard no deal Brexit? Why would the EU want to encourage UK exports to the EU aided by perhaps a 30% cumulative Sterling devaluation rendering EU competitors un-viable? Why not maximize the opportunity to replace UK exports of goods and services with indigenous EU products and services? Can the EU really afford to continue being dependent on a non-member for the production of vital goods and services?

But most importantly of all, why would the EU want to assist the UK in “making a success of Brexit” when that would undermine the very raison d’être of the EU itself? Whereas the UK Brexiteer case for a no deal Brexit is all bluff and bluster, could it be that the EU case is very real indeed?

British expectations for a deal now appear to be wildly unrealistic, involving, as they do, the undermining of the “four freedoms” underpinning the Single Market. Is the only way of achieving a more realistic deal for the EU to wait a few years until the real effects of a no deal Brexit have worked their way into the UK body politic and expectations have been reduced to a point the EU can concede without damaging it’s own internal coherence and stability?

Of course it would seem grossly revangiste for the EU to pursue such a strategy as a first choice, any hint of which EU negotiators have been careful to eschew. But when UK Brexiteers extol the virtues of a no-deal Brexit, they should perhaps be more careful as to what they wish for. A no deal Brexit may very well be what they will get, and their hopes that German car industry executives will come to their aid may be very mistaken indeed.

And with Trump threatening to withdraw from the WTO, the “WTO option” so beloved by hard Brexiteers may not be the “worst case” scenario a no deal Brexit could usher in. If the UK defaults on its €40 Billion exit payment, there may be no incentive for the EU to grant the UK any kind of “most favoured nation” market access at all. No deal doesn’t just mean no deal. It could mean very rapidly deteriorating relationships, mutual recriminations, and ultimately, a trade war.

Brexit may be a full frontal attack on everything the EU stands for, but there is no reason why the EU should fulfill UK stereotypes of an ineffectual bureaucracy and fail to fight back. Brexit may very well become the impetus the EU needs to forge a new unity of purpose and collective self interest. That self-interest may not include giving an ex-member and chief critic an easy ride.