On February 20, in the Financial Times, Martin Wolf finally acknowledged the situation of the American economy and the seriousness of the threats it is facing: America’s economy risks mother of all meltdowns.

Quoting extensively Nouriel Roubini’s February 5 publication The Rising Risk of a Systemic Financial Meltdown: The Twelve Steps to Financial Disaster, he paints a very scary picture of America’s economic future.

Nouriel Roubini is a Professor of Economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business and is also the co-founder and Chairman of RGE Monitor (access to the blog is possible through free registration). He was one of the few economists who predicted an American recession as soon as 2006. At the time, he has been dismissed as a bear and excessively pessimistic.

What follows will not sound new to those who followed Jérôme’s and Bonddad’s diaries. It is however telling that the key FT columnist (and some prominent economists – see the comments below Wolf’s paper) now think that the bleak scenario he was forecasting is very likely to happen.

Let’s read Martin Wolf:

The characteristics of this scenario are, he [Nouriel Roubini] argues: “A vicious circle where a deep recession makes the financial losses more severe and where, in turn, large and growing financial losses and a financial meltdown make the recession even more severe.”

…

Step one is the worst housing recession in US history. House prices will, he says, fall by 20 to 30 per cent from their peak, which would wipe out between $4,000bn and $6,000bn in household wealth. Ten million households will end up with negative equity and so with a huge incentive to put the house keys in the post and depart for greener fields. Many more home-builders will be bankrupted.

Step two would be further losses, beyond the $250bn-$300bn now estimated, for subprime mortgages. About 60 per cent of all mortgage origination between 2005 and 2007 had “reckless or toxic features”, argues Prof Roubini. Goldman Sachs estimates mortgage losses at $400bn. But if home prices fell by more than 20 per cent, losses would be bigger. That would further impair the banks’ ability to offer credit.

Step three would be big losses on unsecured consumer debt: credit cards, auto loans, student loans and so forth. The “credit crunch” would then spread from mortgages to a wide range of consumer credit.

Step four would be the downgrading of the monoline insurers, which do not deserve the AAA rating on which their business depends. A further $150bn writedown of asset-backed securities would then ensue.

Step five would be the meltdown of the commercial property market, while step six would be bankruptcy of a large regional or national bank.

Step seven would be big losses on reckless leveraged buy-outs. Hundreds of billions of dollars of such loans are now stuck on the balance sheets of financial institutions.

Step eight would be a wave of corporate defaults. On average, US companies are in decent shape, but a “fat tail” of companies has low profitability and heavy debt. Such defaults would spread losses in “credit default swaps”, which insure such debt. The losses could be $250bn. Some insurers might go bankrupt.

Step nine would be a meltdown in the “shadow financial system”. Dealing with the distress of hedge funds, special investment vehicles and so forth will be made more difficult by the fact that they have no direct access to lending from central banks.

Step 10 would be a further collapse in stock prices. Failures of hedge funds, margin calls and shorting could lead to cascading falls in prices.

Step 11 would be a drying-up of liquidity in a range of financial markets, including interbank and money markets. Behind this would be a jump in concerns about solvency.

Step 12 would be “a vicious circle of losses, capital reduction, credit contraction, forced liquidation and fire sales of assets at below fundamental prices”.

In all, argues Prof Roubini: “Total losses in the financial system will add up to more than $1,000bn and the economic recession will become deeper more protracted and severe.”

Is this kind of scenario at least plausible? It is.

(emphasis mine)

So, the risks are really high and the capacity of the authorities to deal with them is limited: RGE – Can the Fed and Policy Makers Avoid a Systemic Financial Meltdown? Most Likely Not.. See also Roubini’s latest publication: Anatomy of a financial meltdown

And Martin Wolf concludes:

In the last resort, governments resolve financial crises. This is an iron law. Rescues can occur via overt government assumption of bad debt, inflation, or both. Japan chose the first, much to the distaste of its ministry of finance. But Japan is a creditor country whose savers have complete confidence in the solvency of their government. The US, however, is a debtor. It must keep the trust of foreigners. Should it fail to do so, the inflationary solution becomes probable. This is quite enough to explain why gold costs $920 an ounce.

The connection between the bursting of the housing bubble and the fragility of the financial system has created huge dangers, for the US and the rest of the world. The US public sector is now coming to the rescue, led by the Fed. In the end, they will succeed. But the journey is likely to be wretchedly uncomfortable.

The comments also are worth reading:

Andrew Smithers adds:

I expect to see an increasing level of concern about company balance sheets and this is perhaps already being reflected in the rise in credit spreads and is also indicated by a recent report in the Financial Times: “The global credit crisis is set to spread beyond the financial industry as companies in other sectors are forced to write down the value of their investments, according to the head of [PwC], the largest global audit firm.” Non-financials have also invested in asset backed and mortgage backed securities “It’s not just in the banks”.

And Robert Wade comments:

One of the big questions in situations where large macro adjustments have to be made (as now) is: who takes the hit? In the messy adjustment of the late 1980s, the US basically got Japan to take the hit through the exchange rate: with the Japanese government almost slavishly complying with US requests, the US$ fell sharply against the yen and Japan lent hugely to the US.

In the attempted adjustment of the early 2000s the US against tried to get foreigners to take the hit by letting the $ fall. But China did not play ball. It pegged to the $, built giant surpluses, and bought $ assets to keep the export machine going. Fortunately just at this time securitization technology came on stream to produce an exploding supply of asset-based securities – AAA rated! – for the Asian funds to buy and keep the inflow flowing.

Now this system is unravelling. But China is not Japan, and retains a much stronger bargaining position to reject US demands that China adjust.

…

Moreover, the crisis also discredits the model of a very liberalized, lightly regulated private financial system – and therefore undercuts the all-important longer-term US project to get China to open its financial system to foreign financial firms, which is key to the US strategy for retaining “primacy” and keeping other states asymmetrically dependent on it.

…

With little international cooperation – notably on exchange rates – the adjustment costs are likely to fall largely on US workers through a prolonged period of stagflation (though the inflation part will show up in the statistics as lower than it really is, because food and energy prices are excluded from the index). How convenient for Republicans that a Democrat will almost certainly be president, and a Democratic administration can be made to take the blame.

Those in the bottom 25% of the US wealth distribution will experience a particularly “wretchedly uncomfortable” journey – a sizable part of the Democrats’ support base. For 25% of US households are (or were, in 1999) in “asset poverty”: they have insufficient wealth (including houses) to survive on their own by spending down their wealth in case their income flow stops…

We can expect a sharp increase in class-based political tensions as not just the bottom 25% but also wealthier middle-class households who were relying on rising house and stock market prices to provide them with an “alternative welfare state” (and were therefore happy to see the public welfare state shrivel in response to applauded tax cuts) try to engineer income redistribution to themselves.

In these circumstances another war might be an attractive White House and Congressional option for keeping domestic discontent in check. The breakdown of the US defence budget does indeed look as though the US military is planning for major state confrontations rather than insurgencies.

(emphasis mine)

In his February 21 post, Roubini adds:

Needless to say the latest macro news (the Philly Fed report) and financial news (increase in corporate bankruptcies and LBOs going belly up, monoline deeper mess, trouble in the muni bonds markets, credit spreads widening, etc.) confirm my analysis that the risk of a systemic financial crisis is rising.

In his blog, Paul Krugman already observed:The credit crunch hits students

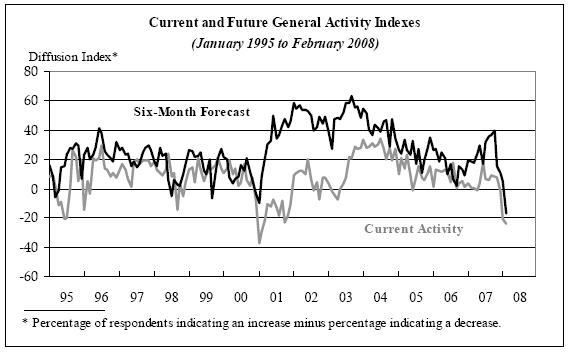

Meanwhile, in the “real” economy: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Business Outlook Survey for February 2008

Activity in the region’s manufacturing sector continued to weaken this month, according to firms surveyed for the February Business Outlook Survey. After falling significantly last month, indexes for general activity, shipments, and new orders remained negative. Despite reporting a weakness in activity, firms continued to report a rise in prices for inputs and their own manufactured goods. Manufacturers’ outlook for the next six months turned noticeably more pessimistic this month.

…

The outlook for manufacturing growth over the next six months deteriorated further this month. The future general activity index declined from 5.2 in January to -16.9, its first negative reading since January 2001 and the lowest reading since 1990. The index has declined 57 points over the past four months.

…

The index for future new orders dropped 17 points and moved into negative territory, while the future shipments index fell eight points but remained positive.This month, the future employment index declined notably. For the first time since 2001, the index fell below zero, declining from 18.8 to minus 8.8.

So Nouriel Roubini is no longer seen as overly pessimistic and all the indicators seem to confirm his scenario likeliness. It is not sure at all that emergency measures like the Fed rate cuts or the recent bailing out of monoline insurer Ambac (see Jérôme’s diary Financial yo-yo and also Zandar1’s The Great Ambac Bailout!) will be enough to stop the downward spiral…