I’ve always been agnostic on whether Michael Jackson did what he was charged with in the trial just ended. Guilty or innocent made no never-mind to me. And now that it’s over, my only advice to Jackson is, however else he lives the rest of his life, that he stay out of bed with young boys, because, well, do I really have to explain?

My interest in the trial was the futile hope that as soon as jurors delivered their verdict and got their thanks from Judge Melville, they’d leave the courtroom and take that raging gorgon Nancy Grace at Headline News with them.

Uh-huh, sure, Nancy. So, then, how about focusing on something besides high-profile, celebrity trials? These are to justice what chicory is to coffee. How about expending some of CNN’s cash and your well-honed legal mind exploring something that affects millions of Americans – the imprisoning of non-violent offenders or the impact of drug laws or the idiocies of mandatory sentencing or the inadequate funding of public defenders or the trying and sentencing of juveniles?

Full disclosure: I have a sealed juvenile offense record. From 1957-59, I spent 23 months of an indefinite sentence at the Industrial School for Boys at the base of Lookout Mountain in Golden, Colorado. A reformatory. I’d like to say it was a frame-up, or excuse myself on the basis of my ethnicity or my mother’s single parenthood. But, no doubt about it, whatever my circumstances, I deserved some re-socialization. I’d been precociously engaging in various kinds of outlawry almost from the day my mother and I arrived in Denver when I was 10. Serial shoplifting, relentless truancy, a couple of grass fires next to apartment buildings, tire slashing, grand theft (a television), running with a gang and bullying. But the crime that got me and five of my mates “sent up the hill” was attempted armed robbery of a gas station. When the cops came, the 75-year-old owner who we thought would be such easy pickings had the six of us, ages 11 to 15, lined up on the pavement with his shotgun pointed at us and our knives on the countertop. The judge wasn’t sympathetic.

Prison, we all called it “prison,” was no picnic. Inmate violence was endemic, and many older boys were hard cases. Guards – who we were forced to call “counselors” – and our teachers were hard cases themselves, a couple of them ex-inmates, and corporal punishment was meted out frequently for minor infractions. I had grim moments, including being gang-raped, for which no one was ever punished.

Part of the “industrial school” process was to teach discipline and also give us JDs a taste of what the work world had in store for us. One lesson many of us had to learn over and over was how to sort nails. A big box – like the size of a 10-ream box of paper – filled with nails of all sizes and types was set on the floor. The lesson went like this: Sort the nails. Get inspected. Correct mistakes. Get approved. Put all the nails back in the box. Repeat. I wasn’t reformed. (That came years later when a man who himself had done a little time in Puerto Rico became my high school Spanish teacher.)

All this occurred long ago, and the toughest juvenile offenders in those days pale beside some who wind up incarcerated these days. At Golden, for instance, I never met a murderer. Today juvenile murder and other violent crimes aren’t so rare, although the alarmist “super-predator” theory so popular in the late 1990s turned out to be bogus. And the media haven’t helped curb the notion of 60% of the public (Californians in this case) that youth are committing most violent crime when, in fact, only 13% of those being arrested for violence at time of the poll were minors.

I’m no Pollyanna when it comes to criminals, especially when their crimes include violence. I’ve contributed money to a victims’ rights group. Thugs and thieves have hurt me and some of my relatives more than once. Even if that weren’t true, I would favor being tough on felons. Particularly repeat felons. Time at hard labor isn’t a sentence that seems the slightest bit unfair to me. Solitary confinement for incorrigibles, likewise.

But being tough isn’t for me the first step, it’s the last. And of late in America, we’ve been skipping some steps called prevention and rehabilitation because somebody decided at the same time it was decided to give stiffer sentences and build more prisons that it also made sense to cut back or hold the line on programs that determine whether we provide justice to everyone in this country. Programs like social services, education, alternative sentencing and, incredibly, parole and probation.

As is obvious from America’s current approach to incarceration – just as in U.S. foreign policy – being tough isn’t enough. You gotta be smart, too, and, dare I say it? compassionate. You don’t have to scratch deep to find grotesque instances of injustice, from innocents railroaded and budget-cutted onto death row to the all-too-familiar racial disparities accompanying drug sentencing. Hundreds of thousands people are doing long time for non-violent crimes that should carry some other punishment. Hundreds of thousands of others who will ultimately join us again in the free population are getting no substance-abuse treatment, no life-skills training, no job training, no anger-management training and no basic education (even though 19% of inmates in 1997 were found wholly illiterate and 40% functionally illiterate). I suppose one could call this policy of intellectual and therapeutic deprivation “tough,” but not compassionate, and definitely not smart, even from the most utilitarian this-guy-will-be-on-the-street-again-someday approach of fearful suburbanites.

As Americans, we now host the biggest free world collection of prisoners on the planet, 2 million-plus of them. We’re putting them away at a higher rate than any other country. And we’re doing a damn poor job of being No. 1.

I sympathize with you, Nancy. Where to begin exploring such a gargantuan mess?

My first choice would be to investigate what happens when convicted juveniles are sentenced to adult prisons. Without knowing the details, everybody knows. It’s a standard movie cliché. Unfortunately, it’s also reality. In prison, young men are targets for rape and other violence. Boys far more so. When these juvenile offenders emerge from the slam, they’ve not been rehabilitated, because most of our adult prisons gave that up long ago. Instead they’ve been hardened, made into perfect candidates for recidivism. If this state-sanctioned child abuse cannot be labeled cruel and unusual punishment, what can?

Florida wised up. It incarcerates youthful offenders sentenced as adults only in all-juvenile facilities because academics, activists and the Miami Herald exposed what had happened under a new 1990s get-tough law. In its Kids in Prison series, the Herald reported that children were far more likely to be attacked or sexually assaulted in an adult prisons than in juvenile facilities. It also took note of studies that juveniles of similar ages who committed similar crimes were more likely to go straight after release if they were sentenced to a juvenile facility than an adult prison.

Until these exposés got the law amended in 2001, not only did Florida put juveniles convicted as adults into cells with adults – with inevitable results – most of the kids they put away weren’t the hardened types legislators had targeted but rather nonviolent teenagers.

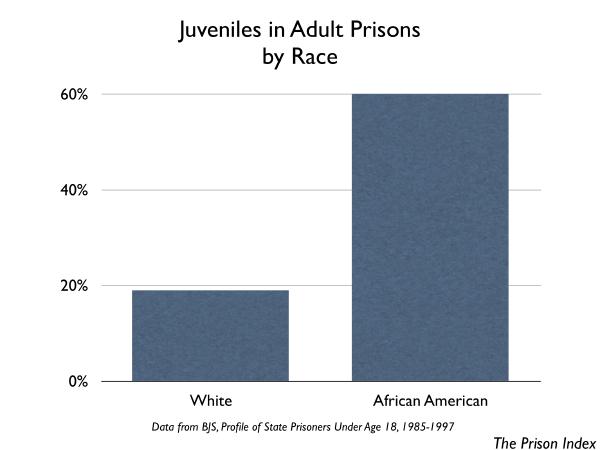

Other states continue to put boys and men in the same cells. Thousands of them nationwide. And not just any boys. Reporters at PBS’s Frontline followed four case histories – two sentenced as juveniles, two as adults – and found a system that, surprise, caters to middle-class white offenders and punishes kids of color. The racial component of this should be no surprise to anyone.

How much the racial component disguises a class component, I don’t know.

At the core of this outrage is the whole philosophy of criminal responsibility. How ludicrous is it that the minimum age for criminal responsibility is 14 in Idaho, 12 in Georgia, 10 in Kansas and Vermont, 8 in Nevada and Washington, and 7!!! in Oklahoma. Twenty-two states allow children to be tried as adults but set no statutory age minimum. The people at Justice Policy Institute have it right. Children are never adults. They should never be sentenced to adult prisons. Nor should they be tried as adults since many of them cannot understand the proceedings against them.

On the other hand, I can’t say a 14-year-old who murders someone in cold blood should be released at 18 or 21. For such children it seems to me we need an intermediate system, not quite juvenile, not quite adult, some way to provide justice to victims and perpetrators alike. Creating that will take some doing.

None of this should be taken to mean that I believe there’s nothing else wrong with the system. Even when juveniles are sentenced and tried as juveniles, we’re failing to be smart and compassionate along with tough, as you can learn at the National Center for Juvenile Justice, at the Center on Juvenile & Criminal Justice and elsewhere.

Some states, like Colorado, have taken action to reform their systems and others, like California, say they’re going to.

Even publicly suggesting the broken justice system needs attention scares many politicians who believe such discussions are electrified. The hint that one is soft on crime can wreak disaster at the polls. So it takes the rare glare of publicity to go against the tide. Bless him, but Illinois Governor George Ryan didn’t just one day put forth a moratorium on death penalty cases, it took two reporters to give him pause.

Nancy, I know prison reform probably doesn’t do as much for the ratings as a high-decibel, prosecutorial rant. But since you don’t care about ratings, how about shining that big media flashlight of yours somewhere useful?