I’ve been hearing about proposed abortion laws that remind me of the Fugitive Slave Act for a while, so I was happy to see Jamelle Bouie tackle the issue head-on in the New York Times’ editorial page. To begin, let’s look at the intent behind these laws.

On Monday, Steve Marshall, Alabama’s Republican attorney general, announced in a court filing that the state has the right to prosecute people who make travel arrangements for women to have out-of-state abortions. Those arrangements, he argued, amount to a “criminal conspiracy.”

“The conspiracy is what is being punished, even if the final conduct never occurs,” Marshall’s filing states. “That conduct is Alabama-based and is within Alabama’s power to prohibit.”

In Texas, anti-abortion activists and lawmakers are using local ordinances to try to make it illegal to transport anyone to get an abortion on roads within city or county limits. Abortion opponents behind one such measure “are targeting regions along interstates and in areas with airports,” Caroline Kitchener reports in The Washington Post, “with the goal of blocking off the main arteries out of Texas and keeping pregnant women hemmed within the confines of their anti-abortion state.”

Alabama and Texas join Idaho in targeting the right to travel. And they aren’t alone; lawmakers in other states, like Missouri, have also contemplated measures that would limit the ability of women to leave their states to obtain an abortion or even hold them criminally liable for abortion services received out of state.

For Bouie, this creates a situation similar to what led to the infamous 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford U.S. Supreme Court decision. The problem back then was the country had a patchwork of laws with respect to black Americans and the institution of slavery. As Bouie explains, slave-dependent states could, “without any objection from the federal government, declare all Black people within their borders to be presumptively enslaved — and that is, in fact, what they did.” He uses the example of South Carolina, which “passed a law in 1822 requiring that all ‘free Negroes or persons of color’ arriving in the state by water be placed in jail until their scheduled departure.” That was their solution to the challenge of free black sailors arriving at their ports.

More of a challenge was what to do about slaves who had escaped or, in Dred Scott’s case, simply been allowed to live his life (for decades, by the time of the final ruling) in Wisconsin without ever formally being freed.

Dred Scott was an African American man who was born a slave in the late 1700s. In 1832, Scott’s owner, Emerson, took him into the Wisconsin territory, which outlawed slavery, to do various tasks. While there, Emerson allowed Scott to get married, and left Scott and his wife in Wisconsin when Emerson traveled to Louisiana. Emerson died in 1843, and Scott attempted to purchase his freedom from Emerson’s widow, but she refused. Scott then sued in federal court against Sandford, the executor of Emerson’s estate for his freedom.

Scott lost his case when the Supreme Court used a version of “original intent” to rule that blacks were never meant to be citizens. The federal government was no help, and it wasn’t the civil war that finally gave Scott his freedom but the widow’s decision to marry an abolitionist who convinced her to relent.

For Bouie, the emerging patchwork of abortion laws are reminiscent of the situation Abraham Lincoln addressed at the 1858 Illinois Republican state convention in Springfield, Illinois, when he said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.”

Of course, by 1861, Lincoln was president and the country was at war with itself and facing dissolution. I guess you can argue both that the federal government was incapable of resolving the issue and that it actually did solve it, but only after resorting to years of brutal fratricidal conflict followed by passing the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Even then, it took another century to win black Americans equal rights under the law.

There is one important difference, however, between the plight of blacks in the 1850’s and the plight of women in the 2020’s. Woman have full citizenship and the right to vote. They don’t have to rely solely on the courts or the slow grind of changing public opinion for those who can vote.

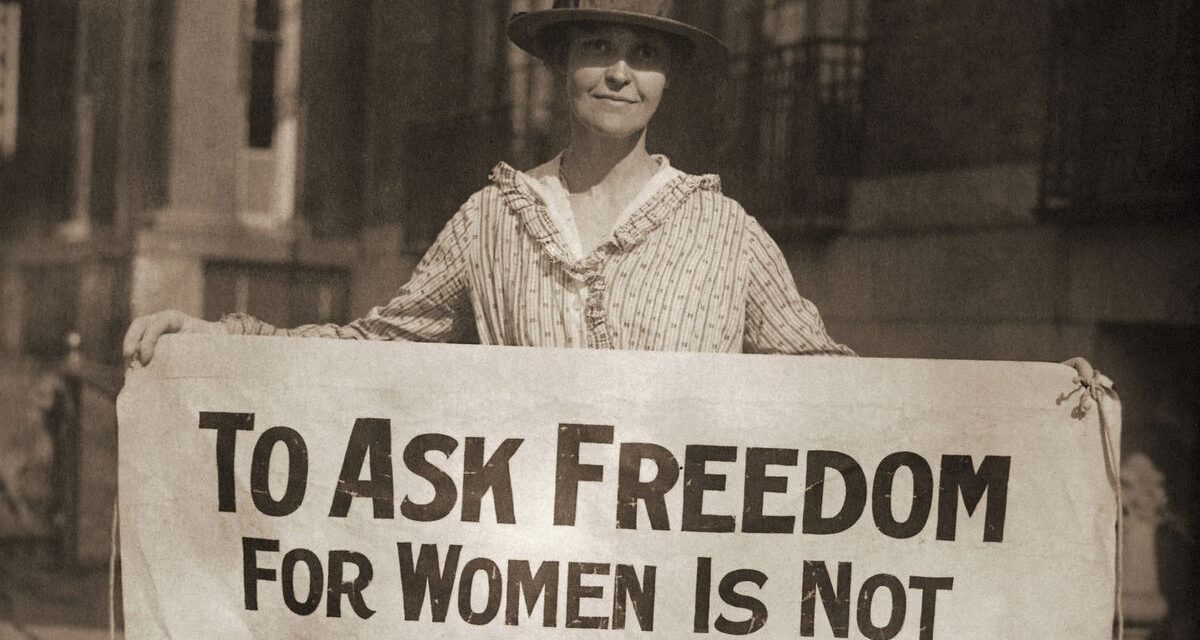

The principles are the same. We shouldn’t have a system where women’s freedom of movement is monitored and restricted in some states and not in others. Women should not be prosecuted in one state for doing something they did in another state. People who help women move from one state to another should not be subject to arrest. There should be one broad set of federal laws and those laws should grant women full rights and autonomy.

But it can take a civil war and a century or more of struggle to right these kinds of wrongs. Women can prevent that outcome by using their political power now, and that’s exactly what I hope will happen. And it needs to begin in the states and localities where these insane laws are cropping up.

.