I kid you not. The year was 1954; I was three years old. My parents had followed some impossible-to-understand dream of moving to the middle of the damn desert and building their very own cinderblock house. So there we were on the distant outskirts of Las Vegas, a little ways off the Tonopah Highway, on our small slice of vast nothingness.

While our new house was under construction, we moved to our temporary quarters, the Atomic Motel. The one feature that distinguished our little home from any and every other cheesy motel in the state of Nevada was its absolutely splendid sign, which I never tired of watching. Approximately 20-30 feet tall, it was a giant neon mushroom cloud. In the style of the day, it started lighting up from the bottom, until the entire mushroom was a vivid and pulsating red — then went black, and then it started the whole lighting-up process over again. Totally mesmerizing.

Hey, that’s me on the cinderblocks!

Hey, that’s me on the cinderblocks!

But, lucky little girl that I was, I didn’t have to limit myself to neon mushroom clouds, oh, no. By 1955, our house was (barely) ready for habitation, and I had the real thing right outside my front door. You see, from January of 1951 through October of 1958, the United States tested 119 nuclear bombs above ground at the Nevada Test Site, at a rate of about one per month. Now, the Nevada Test Site, for those of you who haven’t brushed up on your godforsaken desert geography, is about 70 miles from downtown Las Vegas (and about 60 miles from the wasteland where I grew up).

The blasts were always announced ahead of time but, like NASA launches, were subject to delay depending on weather conditions (we now know that they were waiting for the prevailing winds to blow away from Las Vegas and towards St. George, Utah, but, hey, I digress). Every day, my father had to drive past the local AEC headquarters on his way to and from work, and he quickly deciphered the code they used. There were two lights atop the AEC building, a blue one if the blast was on schedule and a red one if it had been delayed.

So in our household, a blue light meant only one thing: “Set the alarm – we’re getting up early to watch the fireworks!” You see, the members of my family were atomic bomb connoisseurs; we were especially partial to the early morning blasts because they were the really cool ones.

So how to describe it. The actual blast was always in the last moments of darkness, just as dawn was breaking. Now, you know how, in an electrical storm, the lightning flashes will momentarily light up the entire landscape with that really eerie white light? Well, an atomic bomb also lights up the landscape, just as if it were midday, but for a considerably longer period of time and with a far different color palette. First came a flash on the horizon, and then, for ten seconds or so as the fireball rose, the entire desert floor and surrounding hills would be bathed in a rosy-orange glow that was simply stunningly beautiful. A short time later, you would feel the earth trembling, and then finally, almost as an afterthought, “BOOM!”

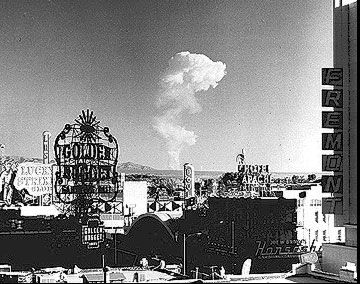

Then, once the big show was over, it was time to go back inside. My dad would shower and shave for work, while my mom started cooking breakfast. Since there was nothing much for me to do, I always hung around outside for my favorite part: watching the mushroom cloud. As time passed, the sky would get lighter and lighter, and the cloud would get taller and taller (some of them went up as high as 20 miles). Finally, by the time it was fully light outside, you could see the different air currents start to carry the cloud away, each current at its own speed and in its own direction. The entire mushroom would start to pull apart and drift off into pieces. And then — “Time for breakfast!”

The wafting mushroom (in perspective).

The wafting mushroom (in perspective).