Image Credits: Photo: Getty Images.

I’ve been sticking my neck out a bit in my early analysis of the Democratic presidential nominating process. For one, my warning that there’s a decent likelihood of a brokered convention is something we hear seemingly every cycle but it never bears out. I feel like a lot of Democrats roll their eyes at this point when “experts” issue that prediction. But there’s a reason I’m making it this time around, and it’s because of the primary schedule and rules for awarding delegates combined with a huge number of candidates. I’m not alone. Leah Daughtry ran the Democratic National Conventions of 2008 and 2016, and she’s quoted in today’s New York Times making the same points:

When Leah Daughtry, a former Democratic Party official, addressed a closed-door gathering of about 100 wealthy liberal donors in San Francisco last month, all it took was a review of the 2020 primary rules to throw a scare in them.

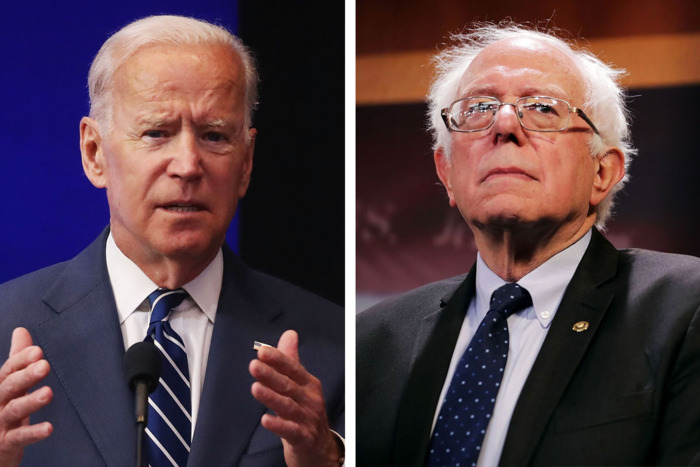

Democrats are likely to go into their convention next summer without having settled on a presidential nominee, said Ms. Daughtry…And Senator Bernie Sanders is well positioned to be one of the last candidates standing, she noted.

“I think I freaked them out,” Ms. Daughtry recalled with a chuckle, an assessment that was confirmed by three other attendees…

…“If I had to bet today, we’ll get to Milwaukee and not have a nominee,” said Ms. Daughtry, who was neutral in the 2016 primary.

I don’t much care about the things that “freak out” wealthy liberal donors, but they should be at least as worried that Bernie Sanders will win outright as that he’d prevail in a brokered convention. In fact, his odds of winning a brokered convention are not that great. His best shot would be if he had a clear and strong plurality of the votes and party bigwigs concluded that denying him the nomination would be so divisive that it would doom their chances of beating Trump. But the superdelegates will be back in play in 2020 if there is no winner on the first ballot at the convention. They’re the ones most likely to determine the winner in that case, and Sanders has not done much better this time around in wooing other elected and party officials over to his side.

The problem for superdelegates and wealthy liberal power brokers is that Sanders is an excellent position to either win the majority of delegates or at least to emerge with the most delegates. I’ve been getting out in front of the pack on that prediction, as well as by repeatedly insisting that Sanders’s strongest rival is former vice-president Joe Biden, assuming he runs.

There have been flavor-of-the-week news cycles for several other candidates. Right now, South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg is enjoying a nice surge into relevancy. Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, and Beto O’Rourke each have each had their own brief time in the spotlight, and they’re all still competing to make news. But the one thing that has remained constant is that Sanders and Biden have enjoyed polling leads both nationally and in the early states, and there is a consistent gap between them and all the others. This isn’t just name recognition. It reflects their superior bases of support at the outset of this contest.

To win delegates, candidates must get at least 15 percent of the vote in some congressional districts within a state. In a three-way race, this is achievable for even the third-place finisher, but it may not even be doable for the second place finisher in some early states where there could be more than two dozen accomplished and decently funded candidates on the ballot. If candidates don’t drop out of the race at the normal rate this time around (and why would they?), then this problem could persist for quite a while. The likely result will be that the top two finishers get almost all the delegates.

You can understand this better by looking at the primary schedule. On March 3, 2020, just four days after the South Carolina primary closes out the four early contests, there will be ten states voting on Super Tuesday, including large ones like Texas, Massachusetts and Virginia. Once those votes are counted, almost 40 percent of the total convention delegates will have been at least preliminarily decided. Sanders and Biden could emerge as the only candidates still capable of winning an outright majority by that early date.

It appears that some of my early predictions are seeping into the consciousness of the party’s power brokers, because we’re now seeing stories about how they’re wringing their hands trying to figure out how to stop Bernie. The truth is, it may not be possible to stop him. Yet, it won’t be easy for anyone to win on the first ballot.

The flip side of the delegate allocation process is that the state winners don’t really net a big delegate advantage. This is why Hillary Clinton had such a hard time coming from behind in 2008 and Bernie Sanders had the same problem in 2016. In both cases, they were all-but mathematically eliminated at a fairly early stage of the game, yet neither of them would face reality. They stuck it out to the end, and they actually seemed to do better after their situations were hopeless. This could have been related to buyer’s regret, especially because late primary voters did not actually buy into the presumptive nominee since they had not yet cast their ballots.

One reason Obama was able to build an insurmountable lead is that he did a better job of losing well. A lot of congressional districts have an even number of delegates to award, and when Obama was able to pass the forty percent threshold in a district he was assured of getting a tie. Obama almost always met that threshold, but there were a lot of districts where Hillary did not. He also rolled up big margins in some caucus states, netting the same number of votes out of the Idaho caucuses, for example, as Clinton netted out of the New Jersey primary that was held on the same day.

Because it’s highly unlikely that before the end stages of the campaign any two candidates will both surpass forty percent in the 2020 contests, it should be a little easier for state winners to take away a good haul of delegates, and that means coming from behind could be somewhat easier. That really depends on how many candidates are reaching the fifteen percent threshold and peeling off small handfuls of delegates. So much will depend on how many candidates are on the ballots and still getting votes.

The most likely cause of a brokered convention that I see is that Sanders and Biden dominate early but then a combination of other candidates getting hot and a bit of buyer’s remorse taking hold results in different winners in the middle and late contests, after it’s too late for any late-surging candidate to win a majority of the delegates. Obama and Clinton were able to limp to the end and carry majorities to the convention, but Sanders and Biden might not be able to repeat that achievement.

Even in that scenario, though, their strong bases of support make it likely that they’d be meeting the fifteen percent threshold in most congressional districts and so they’d still be adding to their totals even if their margins were slipping.

I can definitely see a situation where there are two main rivals for the nomination at the convention. It would basically be the early leader who has the most overall delegates (quite possibly either Sanders or Biden) versus the surging candidate who won the majority of the late contests but might only be in third place in total delegates.

You can have fun trying to game out what that might look like. It would be a totally different picture for the party if Sanders arrived in Milwaukee in a prolonged slump but with the most delegates than if the same thing happened to Biden. If the late-surging candidate were a woman or a minority (or both) or a millennial, that would add more fractious acrimony to the whole process.

You can be sure that the Republicans (and probably the Russians) will be ready will gallons of gasoline to pour on that kind of fire.

I’d rather be predicting that someone will emerge that is broadly acceptable to all factions of the party and that they will waltz to the nomination with a clear and early majority of the delegates. It could definitely happen, and so I don’t recommend that you spend a lot of time freaking out. I’m doing enough freaking out for the both of us.