I have been posting this around the internet to get some feedback and hopefully some help. Since Booman seems to have a little more international flavor, I thought I might get a different perspective here.

What follows is a very personal account of a non-political project I have been working on. Some of you might be familiar with the efforts I have been doing on behalf of East Africa, and I will continue those. But this diary is much more personal and comes out of a quest I started some three years ago, delving into my genealogy and finally actually visiting the town in Latvia where one branch of my ancestry came from. What I found there was a Jewish population that had almost been wiped out by the Nazis and that may yet die out, fulfilling, in part, Hitler’s dream of eliminating Jews from Europe. There is one surviving synagogue in that town, though it is now a condemned building. That building has stood through 160 years of weddings and pogroms, hope and the Holocaust.

In 1845, the small East Latvian town of Rezekne (or Rezhitsa in Russian) was part of the massive Russian Empire that stretched from Poland to Siberia. In that year, a small wooden syangogue was built in Rezekne. This synagogue was one of about a dozen synagogues in the city of Rezekne in the middle years of the 19th century, synagogues that served a large Jewish population, about half the total population of Rezekne at that time. This particular synagogue was painted green, and hence the building has been known ever since as simply the “Green Synagogue.” The Green Synagogue is the only synagogue in Rezekne to survive World War II, and even now it stands, though only as an empty, condemned building. It also, from what I can tell, was the synagogue where my great-grandparents were married before they fled Russia and came to the United States. Like the Jewish population in many corners of Eastern Europe today, the Green Synagogue is in danger of being forgotten and lost.

Rezekne is a city that was shaped by an interaction of cultures: native Latvian, German, Russian and Jewish cultures mixing both peacefully and violently. Rezekne was originally a castle town and the ruins of its castle, possibly dating as far back as the 9th century, remain today. This castle was one of the first buildings built in Rezekne. But signs of a Jewish presence are just as old since right next to the ruined castle is another old building that is thought to have been the town’s first inn, and this inn was thought to be run by Jews from very early on. This was a very common pattern in Eastern Europe, with Jews running local inns and taverns next to the local castle. Those who remember the drunken dancing tavern scene in Fiddler on the Roof will remember that the tavern was run by a Jew and patronized by both Jews and non-Jews. This was typical even as early as the Middle Ages and as late as the 19th Century. The Jewish population of Rezekne grew as the city grew until half the city was Jewish. This was no little shetl, but neither was it a big city. Even as late as 1808 Rezekne was described as having only one street and no skilled craftsmen. But even so, at that time Jews participated fully in city life, including sitting on the city council. Jews were an integral part of Rezekne’s life until World War II.

My great-great grandfather, Schmuila Jankel Luban, was 24 years old when the Green Synagogue was built. Jankel’s last name, Luban, was probably only recently adopted by the family, since it was only around that time that Jews commonly took last names in Eastern Europe. Before being forced by the government to take last names, Jews just went by “So-and-so, son of Whosits.” “Luban” indicates that the family was originally from a shtetl near Lake Lubanas, also in Eastern Latvia. The Lubans were a family of craftsmen, not well off, but not so poor either. Jankel married a woman named Kreine and they lived not too far from the Green Synagogue. Jankel is the earliest Jewish ancestor of mine I can trace. In his honor, my wife and I named our son “Jacob,” linking my son with his Latvian-Jewish heritage.

We don’t know when Jankel and Kreine died but there is no record that they ever left Rezekne. The last record of their existence is their entry in the 1897 “All Russia” census where I was able to learn of their existence and even the address where they lived. But two of their sons, Sawel and Henach, fled Russia for America with their families by 1905, fleeing political unrest, military conscription and pogroms. Henach had been forced to serve in the Russian army in the ill-fated Russo-Japanese war and when on leave he fled Russia rather than being sent back to the front. Both Sawel and Henach had married and had children by the time they fled Russia. In fact, my grandmother was the last member of these two families to be born in Rezekne. Since both families lived near the Green Synagogue, it is very likely that when they married, Sawel and Henach had their weddings at the Green Synagogue. Both families settled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin where some of my distant relatives still live. Sawel became Solomon Luban in America and was my great grandfather.

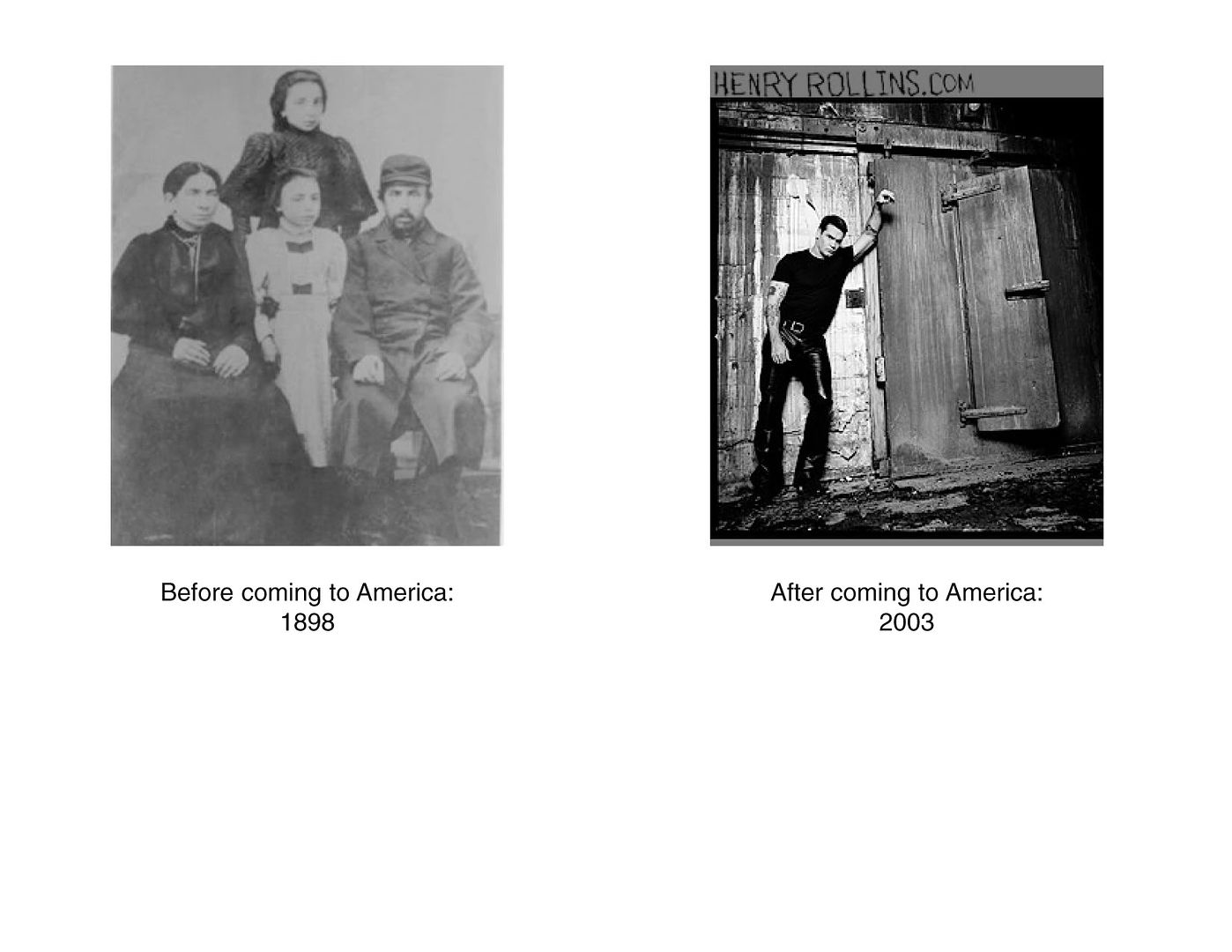

Henach became Henry Luban in America and many of his children, grandchildren and further descendents are still alive. One such descendent of Henry Luban’s is his great-grandson Henry Garfield, better known to many of us as the punk rocker Henry Rollins.

There are vague hints that one or two other Luban brothers may have existed. There is a record of a Berko Luban running a store in Rezekne in 1911 and a photograph marked “David Luban” from London where Solomon also had his picture taken when he was on his way to America. The photograph is very striking, and could well resemble the photos of my great-grandfather, but we may never know. By the time I was born, all memory of Berko and David Luban had faded, as had any memory of the Green Synagogue. By the time I was an adult and searching for my roots, many of us had even forgotten that we were from Rezekne at all.

While my family was thriving in America and forgetting about Rezekne, the Jewish population left behind suffered terribly. Emigration, starvation, pogroms and forced relocation reduced the Jewish population of Rezkne considerably by the time World War II started. But the Green Synagogue survived. It was even renovated in the 1930’s. When the Germans came, in one single day, 5000 Jews and the Latvians who tried to help them were machine-gunned just outside of town. I visited the place, the only actual Holocaust site I have ever visited. Walking along the grassy space that is the mass grave, walking for a very long time along that grave, the impact of “5000 killed in one day” hit home very hard and I had tears in my eyes and a great deal of anger in my heart.

The Jewish population of Rezekne was almost wiped out on that single day. Only a handful survived, protected by some local Latvians. By the time many members of my family were returning to Europe as soldiers in the US military fighting the Nazis, those Nazis had all but wiped out any of our relatives who had remained in Rezekne.

But somehow, the Green Synagogue survived. All other synagogues in Rezekne were destroyed, and the Jewish graveyard was shot at. You can still see bullet holes in some of the surviving gravestones. But the Green Synagogue still stands. Some remember that it was used as a holding pen for Jews on their way to death camps and that this is why it survived. Rezekne is on a major railroad route between St. Petersburg and Warsaw, so Jews from all over the region were brought into town to await transport to the camps. Rezekne was one small node on a massive railroad network feeding the death camps. The Green Synagogue was the last synagogue many of those people would ever see.

In 2003, after I had rediscovered my family’s past and found the addresses where we had lived in 1897 in Rezekne, I went to visit the city of my great-great grandfather to see where we had come from. I took my wife and stepdaughter and we met with Rashel, the head of the Jewish community of Rezekne, to see the city and to learn what it was like when my family had lived there.

The city itself is beautiful, though we saw some remnants of lingering anti-Semitism. But overall our brief stay in Rezekne was very pleasant. The countryside is beautiful, the town small and quiet. It is a part of Latvia that is more Russian than Latvian, and most restaurants had Russian menus and served Russian food. Some of the best Russian food I have ever tasted was in a restaurant just down the street from where Henry Rollins’ great grandmother’s family had lived.

Today only about 50 Jews remain in Rezekne. They have no proper synagogue since the Green Synagogue was condemned in the 1990’s due to severe water damage. Their shul is a handful of rooms in an office building. Rashel showed me the addresses where my family used to live. Some buildings, like the one where my great grandparents lived, are gone. But some, like the brick apartment building where Henry Rollin’s great grandmother’s family lived, still stand. And many of those addresses are near the Green Synagogue, suggesting to me that the Green Synagogue was our family’s synagogue.

Our tour of Jewish Rezekne ended at the Synagogue and it was there that Rashel told me much of what I have told you here. We saw the synagogue by candlelight. The inside is dusty and water damaged with many windows boarded up and parts of the ceiling falling down.

It was a very sad building with some old paintwork from the 1930’s if not earlier and even a few fragments of the original stained glass. I stood there that day in the condemned Green Synagogue and imagined the wedding of my great grandparents. My ancestors had probably stood in that same synagogue more than 100 years before I did. And then I imagined thousands of terrified Jews in the 1940’s spending one night in that same synagogue before being sent to almost certain death.

The joys of weddings and the fear of death surrounded me in that dark, sad building. It was at that moment that I decided that I would try and save the Green Synagogue. As a monument to the Jews who had helped shape Rezekne from its early days as a castle town to its later days as a stop along a major Russian rail line, I wanted to save that synagogue. As a place for my family to return to see where we came from, I wanted to save that synagogue where at least two generations of my family probably got married. As an act of defiance against the Nazis who practically wiped out the Jews of Rezekne, I wanted to save that synagogue. And as a symbol of hope for the surviving Jews of Latvia, I wanted to save that synagogue.

I had never undertaken this kind of project before and had no idea how to go about it. But I was very lucky that the local government of Rezekne had already taken an interest in restoring the Green Synagogue. One of the adjacent streets was renamed “Israel Street” in its honor and they had looked into what it would take to restore. Sadly, they dropped the plan due to lack of funds. So I decided that maybe I could help find at least some of the funds needed to restore the Green Synagogue and so, soon after returning to the US after my trip to Rezekne, I went online to find funding agencies that might be interested and to find Jews descended from Rezekne Jews who might be able to help me. I was able to find some two-dozen descendents of Rezekne Jews who were interested in helping restore the Green Synagogue and without their help and advice, I would never have even been able to begin. And it is through this network of Jewish descendents of Rezekne Jews that I was able to get the ball rolling.

About a year after returning from Rezekne, I was able to get a small grant from the World Monuments Fund’s ™ Jewish Heritage Grant Program that would cover the cost of hiring an architect to survey the site of the Green Synagogue and determine what work needed to be done and how much a full restoration would cost. That phase of the project has recently been completed and now the real work can begin. The local government in Latvia, inspired by the interest that I and the World Monuments Fund were showing, was able to find more than $40,000 to repair the roof, so that no further water damage will occur, and to repair the timbers that have been most damaged. But this is only the beginning. The site survey that the World Monuments Fund supported has found that nearly $200,000 worth of repairs will be needed to restore the synagogue to the way it was in the 1930’s. I am hoping to find people who are interested in preserving this small piece of Eastern European heritage, in defying the Nazi attempts to eradicate all signs of Judaism in Europe and in giving hope to the surviving Jews of Latvia. I invite anyone who can help raise money or interest in this project to contact me so that the Green Synagogue, which has stood for 160 years of both joy and despair, can continue to stand for the Jews of Rezekne.