I know, I know, another old white guy. I know. I don’t like it either. But what are you going to do? You go to war with the progressive liberal prairie populist you have, not the one you want. Paul Wellstone is dead, for godsakes, it’s time to move on.

And if you are looking, as I am, for a liberal progressive prairie populist, who can you turn to within the Democratic Party establishment? Clinton? Biden? Kerry? Gore? Edwards? Obama?

I like Gore and Edwards. I will support any Democrat over any Republican. I will support tweedle-dee over tweedle-dum.

But before I do I want to find someone to really believe in before I compromise for expediency, electability and political stratgery.

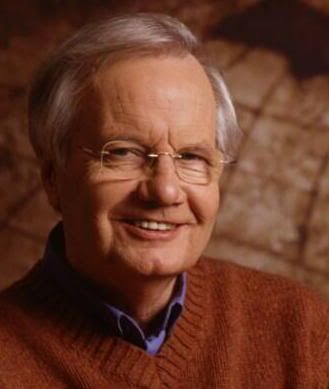

For me, that person is an old white guy. Bill Moyers.

Here is the real political story, the one most politicians won’t even acknowledge: the reality of the anonymous, disquieting daily struggle of ordinary people, including the most marginalized and vulnerable Americans but also young workers and elders and parents, families and communities, searching for dignity and fairness against long odds in a cruel market world.

Moyers gets it. Moyers is all about the story. America’s story. The conservatives have been successful in supplanting the American Dream – the idea that the least amongst us has the same opportunity for life, liberty and happiness as the elite of the elites – with a tale of greed and gluttony masked in the nobility of individual rights and the sanctity of private property. The conservative mythology is used to build walls around the rich, employ government for the service of elites and institutionalize the haves and the have-nots.

Reagan’s story of freedom superficially alludes to the Founding Fathers, but its substance comes from the Gilded Age, devised by apologists for the robber barons. It is posed abstractly as the freedom of the individual from government control – a Jeffersonian ideal at the root of our Bill of Rights, to be sure. But what it meant in politics a century later, and still means today, is the freedom to accumulate wealth without social or democratic responsibilities and the license to buy the political system right out from under everyone else, so that democracy no longer has the ability to hold capitalism accountable for the good of the whole.

America was not founded and built as a playing field for individuals to amass the wealth of kings. America was founded as a union of people, a society built for the common good.

And that is not how freedom was understood when our country was founded. At the heart of our experience as a nation is the proposition that each one of us has a right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” As flawed in its reach as it was brilliant in its inspiration for times to come, that proposition carries an inherent imperative: “inasmuch as the members of a liberal society have a right to basic requirements of human development such as education and a minimum standard of security, they have obligations to each other, mutually and through their government, to ensure that conditions exist enabling every person to have the opportunity for success in life.”

The quote comes directly from Paul Starr, one of our most formidable public thinkers, whose forthcoming book, Freedom’s Power: The True Force of Liberalism, is a profound and stirring call for liberals to reclaim the idea of America’s greatness as their own.

A free, democratic and prosperous society embodies the notion, alien to the corporate spawn of Cain, that we are our brother’s keeper. Poverty, disease and inequality is the failure of a just society to fulfill its obligations to all of its members.

John Schwarz, in Freedom Reclaimed: Rediscovering the American Vision, rescues the idea of freedom from market cultists whose “particular idea of freedom…has taken us down a terribly mistaken road” toward a political order where “government ends up servicing the powerful and taking from everyone else.” The free-market view “cannot provide us with a philosophy we find compelling or meaningful,” Schwarz writes. Nor does it assure the availability of economic opportunity “that is truly adequate to each individual and the status of full legal as well as political equality.” Yet since the late nineteenth century it has been used to shield private power from democratic accountability, in no small part because conservative rhetoric has succeeded in denigrating government even as conservative politicians plunder it.

But government, Schwarz reminds us, “is not simply the way we express ourselves collectively but also often the only way we preserve our freedom from private power and its incursions.” That is one reason the notion that every person has a right to meaningful opportunity “has assumed the position of a moral bottom line in the nation’s popular culture ever since the beginning.” Freedom, he says, is “considerably more than a private value.” It is essentially a social idea, which explains why the worship of the free market “fails as a compelling idea in terms of the moral reasoning of freedom itself.” Let’s get back to basics, is Schwarz’s message. Let’s recapture our story.

Ah yes, our story, the one lost in the haze of the right-wing noise of robber barons, monopolists and an arrogant aristocracy of the ‘money power’ who know full well what would happen to them if their politicians and free press were not wholly owned lock, stock and barrel by the elite themselves.

Norton Garfinkle picks up on both Schwarz and Starr in The American Dream vs. the Gospel of Wealth, as he describes how America became the first nation on earth to offer an economic vision of opportunity for even the humblest beginner to advance, and then moved, in fits and starts-but always irrepressibly-to the invocation of positive government as the means to further that vision through politics. No one understood this more clearly, Garfinkle writes, than Abraham Lincoln, who called on the federal government to save the Union. He turned to large government expenditures for internal improvements-canals, bridges and railroads. He supported a strong national bank to stabilize the currency. He provided the first major federal funding for education, with the creation of land grant colleges. And he kept close to his heart an abiding concern for the fate of ordinary people, especially the ordinary worker but also the widow and orphan. Our greatest President kept his eye on the sparrow. He believed government should be not just “of the people” and “by the people” but “for the people.”

The great leaders of our tradition – Jefferson, Lincoln and the two Roosevelts – understood the power of our story. In my time it was FDR, who exposed the false freedom of the aristocratic narrative. He made the simple but obvious point that where once political royalists stalked the land, now economic royalists owned everything standing.

Mindful of Plutarch’s warning that “an imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics,” Roosevelt famously told America, in 1936, that “the average man once more confronts the problem that faced the Minute Man.” He gathered together the remnants of the great reform movements of the Progressive Age-including those of his late-blooming cousin, Teddy-into a singular political cause that would be ratified again and again by people who categorically rejected the laissez-faire anarchy that had produced destructive, unfettered and ungovernable power.

Now came collective bargaining and workplace rules, cash assistance for poor children, Social Security, the GI Bill, home mortgage subsidies, progressive taxation-democratic instruments that checked economic tyranny and helped secure America’s great middle class. And these were only the beginning. The Marshall Plan, the civil rights revolution, reaching the moon, a huge leap in life expectancy-every one of these great outward achievements of the last century grew from shared goals and collaboration in the public interest.

So it is that contrary to what we have heard rhetorically for a generation now, the individualist, greed-driven, free-market ideology is at odds with our history and with what most Americans really care about. More and more people agree that growing inequality is bad for the country, that corporations have too much power, that money in politics is corrupting democracy and that working families and poor communities need and deserve help when the market system fails to generate shared prosperity. Indeed, the American public is committed to a set of values that almost perfectly contradicts the conservative agenda that has dominated politics for a generation now.

The key, according to Bill Moyers is not in trying to change the minds of people but reach folks with the story they would embrace if only they were allowed to hear it.

One story would return America to the days of radical laissez-faire, when there was no social contract and the strong took what they could and the weak were left to forage.

The other story joins the memory of struggles that have been waged with the possibility of victories yet to be won, including healthcare for every American and a living wage for every worker. Like the mustard seed to which Jesus compared the Kingdom of God, nurtured from small beginnings in a soil thirsty for new roots, our story has been a long time unfolding.

It reminds us that the freedoms and rights we treasure were not sent from heaven and did not grow on trees. They were, as John Powers has written, “born of centuries of struggle by untold millions who fought and bled and died to assure that the government can’t just walk into our bedrooms and read our mail, to protect ordinary people from being overrun by massive corporations, to win a safety net against the often-cruel workings of the market, to guarantee that businessmen couldn’t compel workers to work more than forty hours a week without extra compensation, to make us free to criticize our government without having our patriotism impugned, and to make sure that our leaders are answerable to the people when they choose to send our soldiers into war.”

The eight-hour day, the minimum wage, the conservation of natural resources, free trade unions, old-age pensions, clean air and water, safe food-all these began with citizens and won the endorsement of the political class only after long struggles and bitter attacks. Democracy works when people claim it as their own.

All great change in our country did not come from the political class, but from the working class. America runs best when it is run grassroots from the bottom up.

I like Bill Moyers. I always have. For an old white guy, I think he is pretty cool. He is a professional journalist, writer and communicator. He’s a celebrity, but he ain’t no movie star.

He is the kind of person we need to speak truth to the power of bipartisan corruption, malfeasance and the willing suspension of listening to the wants, needs and aspirations of a truly free people in an open, democratic and enlightened society.

He is the quintessential philosopher king. And after years of village idiocy, maybe what the American village needs is a bit of common fucking sense.

Anyway, I doubt old Bill wants to be President of the United States.

And more’s the pity.

But as it stands, with everything I know about the 2008 election and its potential candidates, in my opinion, Bill Moyer’s is the best choice for President of the United States.

Crossposted from My Left Wing