Since it’s awards season, I am ranking documentaries about politics, government, social issues, and the environment by counting up how many nominations and wins each film has earned at what I’m counting as the major awards shows and programs that recognize documentaries. I’m counting films recognized by the Black Reel Awards, Cinema Eye Honors Awards, US, Critics’ Choice Documentary Awards, Environmental Media Awards, USA, Film Independent Spirit Awards, Gotham Awards, International Documentary Association (IDA) Awards, National Board of Review, Online Film Critics Society Awards, Producers Guild Documentary Awards, and Satellite Awards. I also included two points for the Emmy Award that went to LA 92. For every nomination, the film earns one point and every win, the film earns another point for a total of two. Only movies that earned two or more points made the list, as they either won an award or were nominated for at least two awards; movies with only one nomination got left off.

After adding up all the points, I’ve ranked the qualifying films as follows with films having the same score arranged alphabetically. To see the awards and nominations, click on the link in the title to read the relevant IMDB page.

Strong Island 12

City of Ghosts 11

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail 10

Chasing Coral 9

Cries from Syria 9

Ex Libris: New York Public Library 9

Quest 8

An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power 7

Icarus 7

Whose Streets? 7

The Work 6

Dolores 5

LA 92 5

Last Men in Aleppo 5

Rat Film 4

Hell on Earth: The Fall of Syria and the Rise of ISIS 3

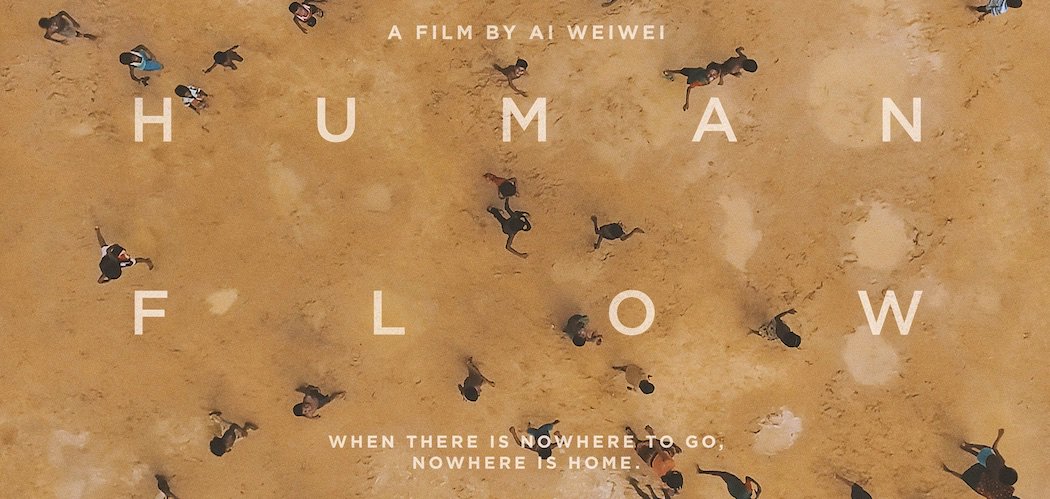

Human Flow 3

Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992 3

Eagles of Death Metal: Nos Amis (Our Friends) 2

That’s an impressive list of worthy films. I don’t envy the documentary branch of the Motion Picture Academy; they had their work cut out for them, as there were 170 eligible documentaries this year. The top five from my list alone would make for a good Oscar field, but that won’t happen, if for no other reason than the fifteen film short list has already been released and “Cries from Syria” did not make it. In addition, “Faces, Places,” “Jane,” “Long Strange Trip,” “One of Us,” and “Unrest,” which are not on my list, have made the Oscar shortlist and are as good as any of the my top five. On top of which, “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power” also made the Oscar shortlist and could make the final five based on it’s being a sequel to a previous winner and as a response to the current political climate. If so, it would probably replace “Chasing Coral,” which would be a shame, if understandable. As I have found out by examining awards shows, not every electorate is the same and the pool of voters matters.

Follow over the jump for the films arranged by general subject along with their plot summaries and my commentary.

Race and Injustice

The largest block of movies are about the unequal treatment of racial minorities, mostly but not entirely African-Americans, by government, particularly the justice system. This includes the highest ranked film, “Strong Island.” Alissa Wilkinson of Vox noted the theme of crime and injustice in her review of the top documentaries of the year.

One of the most celebrated documentaries in 2017 was Yance Ford’s Strong Island, a searing personal account of Ford’s grief, frustration, and struggle following the murder of his brother — a black man killed by a white man, investigated by a justice system that doesn’t seem interested in solving the case. The film is both emotional and pointed, with Ford attempting, on camera, to determine what really happened and what that means for self, family, and country when justice is so frequently crossed with prejudice. The camera often pulls in close to his face as he speaks directly to us, but we’re not the only ones being addressed; Ford is mining memory and experience, retreading paths that are painful in search of answers that may never come. But that lack of resolution, as uncomfortable as it is for us as the audience, is the point.

“One of the most celebrated documentaries of 2017” is absolutely right with two awards and eight nominations.

Speaking of celebrated documentaries, the next film covering this general subject, “Abacus: Small Enough to Jail,” has won four awards from the shows and programs I am using, including Best Political Documentary from the Critics’ Choice Documentary Awards. The Guardian review explains why it belongs here.

Veteran documentary-maker Steve James (Hoop Dreams) is back with an engrossing story: the extraordinary fiasco of the Abacus bank prosecution. It is a tale of hypocrisy, judicial bullying and racism. Abacus was a small neighbourhood bank serving New York’s Chinese community, which discovered a crooked employee falsifying mortgage documents, duly reported the matter to the authorities, but then found itself prosecuted by a district attorney who had sniffed a post-2008 PR opportunity to collar some real live bankers.

“Model minority” or not, Asian-Americans experience systemic racism, too.

“Quest” probably displays the least injustice of the movies telling the stories of African-Americans, but it still puts their experience in a political context, as Vox notes.

But the portrait that sticks with me most from 2017 is found in Jonathan Olshefski’s film Quest, a documentary portrait of a North Philadelphia family shot over a decade. Quest is a cinéma vérité documentary portrait of the Rainey family, who operate a recording studio. But life (and movies) doesn’t always go as planned, and when tragedy hits the family, the documentary takes an unexpected turn. It is, by far, one of the most moving documentaries of the year, and vital viewing that somehow captures the past 10 years of the American experience — including life in the city as well as the broader political and social situation in America — better than either the Raineys or Olshefski could have ever imagined.

Out of all the documentaries about the general theme of the minority experience in America and the injustices associated with it, only one received nominations from both the Black Reel Awards and the NAACP Image Awards, “Whose Streets?” about the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. Rolling Stone had the most vivid review.

You might think for a nanosecond that, after seeing footage of the protests and push-back in Ferguson, Missouri, played in TV-news loops during the back half of 2014, those images might have lost the ability to shock or stun you. And then you bear witness to the scenes of cacophony and chaos in Whose Streets?, the extraordinary documentary by Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis – the tear gas and the tanks and bodies being slammed down on the ground – and your rage starts to play catch-up to the rage emanating from behind the camera. A boots-on-the-ground portrait of the aftermath of Michael Brown Jr.’s murder and the sparks of a movement that sprang from it, this impressionistic collection of testimonies, frontline dispatches and citizen journalism could not feel more essential. Whether it’s the “best” documentary of 2017 is a matter of opinion. But it is assuredly the most vital.

No examination of crime and injustice would be complete without an examination of prison life. “The Work” does just that, as Vox reports.

But one of the very best films of the year was Jairus McLeary and Gethin Aldous’s The Work, which lets the audience sit just outside a circle of men — some incarcerated, some from outside the prison walls — engaging in intense, four-day group therapy at Folsom Prison. The Work spends almost all of its time inside the room where that therapy happens, observing the strong, visceral, and sometimes violent emotions the men feel as they expose the hurt and raw nerves that have shaped how they encounter the world. Watching is not always easy, but by letting us peek in, the film invites us to become part of the experience — as if we, too, are being asked to let go.

Leaving behind the African-American experience for the Mexican-American one, “Dolores” follows the life of the co-founder of the United Farm Workers. My former hometown paper, the Los Angeles Times, explains.

“Dolores” is a documentary that celebrates a hero, but it’s no hagiography. Its subject wouldn’t stand for that.

That would be Dolores Huerta, a legendary activist who at age 87 defines indefatigable, a woman whose experience shows what a life of total commitment means — as well as the price it demands.

Huerta has been jailed, seriously beaten, mocked by commentator Glenn Beck and given the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama. Yet she doesn’t have the name recognition of her close collaborator, Cesar Chavez, something director Peter Bratt is determined to change with this vivid, informative and heartening documentary.

Huerta was the co-founder, along with Chavez, of the United Farm Workers union. She’s also the person who came up with that organization’s celebrated slogan, “Si, se puede” — yes, we can — someone whose tireless activism has extended to feminism, the environment and the political process.

I should have known about Dolores Huerta a long time ago. I’m glad I finally did.

I’m examining two films on the same topic, breaking with my going strictly on points. They are “LA 92” and “Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992,” both about the Los Angeles uprising of 25 years ago. The former, which won the Primetime Emmy for Exceptional Merit in Documentary Filmmaking, made the Oscar shortlist. It tied for the second lowest scoring film according to my metric to make the shortlist, but it also beat both of last year’s Oscar winning documentaries, “O.J.: Made in America” and “The White Helmets,” at the Emmy Awards, so I think the documentary branch did the film, the industry, and the audience a service by including it.

I return to the Los Angeles Times, which reviewed both films together in an interesting comparison and contrast.

Riots or rebellion? Anarchy or insurrection? Unrest or uprising? Whatever words are used to categorize it, as the 25th anniversary approaches of the frenzy of violence that swept Los Angeles beginning April 29, 1992, attention is being paid. A lot of attention.

No fewer than five documentaries are being broadcast about those events, and no wonder. For one thing, the havoc caused was considerable, with more than 50 people killed, thousands injured and roughly a billion dollars in property damage sustained. Wherever you were in the city, you could see the smoke of a metropolis attacked by flames.

And though a quarter-century is past, the events that began with a notorious acquittal in the trial of four police officers for the beating of Rodney King are far from settled history. And the societal situations that caused them are no closer to resolution.

Two of those five documentaries are going to have theatrical releases before their TV airings. Though their aesthetic approaches are almost diametrically opposed, the skill with which each has been made enables them to in effect speak to each other. Seen back to back, these two documentaries have a powerful, even explosive impact even though they both cover essentially the same events.

…

The documentary opening first in theaters — on April 21 for one week at the Laemmle Music Hall in a version that is nearly an hour longer than the one that will be broadcast on ABC on April 28 — is John Ridley’s “Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992.”Though it has its share of excellent footage from back in the day, the strength of “Let It Fall” is in its remarkable contemporary interviews, compelling both for the people recorded and the way the conversations are allowed to unfold.

“LA 92,” at the Laemmle Noho on April 28, two days before it is broadcast on the National Geographic Channel, takes the opposite tack. Directed by Dan Lindsay and TJ Martin, who won an Oscar for “Undefeated,” “LA 92” intentionally avoids interviews and constructs a narrative entirely through immersion in archival footage.

“Let It Fall” is on Netflix, and it might just get a second chance at the News and Documentary Emmy Awards next year. In fact, I think a bunch of these films, which are also on streaming services or being shown on PBS or cable, may make for a crowded and quality field in the documentary categories at the next awards.

When I first read the title of the next movie, I thought, oh, cool, an environmental movie I can come back to later. Vox set me straight, showing that it belongs with films about racial injustice.

The very best essay-style documentary I saw this year was Theo Anthony’s Rat Film, which explores “redlining,” eugenics, and Baltimore’s racial history through the lens of the city’s most notorious rodent, the rat. It is a barnburner of a movie, one that flicks back and forth through different pieces of an argument, which manifest themselves in very different ways. Sometimes we’re just listening to a guy talk. Sometimes we’re watching maps take on different colors. Sometimes we’re literally watching rats. But the larger point, which slowly emerges as Anthony builds his argument by trying out the ideas next to one another, is that the roots of many social problems in Baltimore — and elsewhere in America — come from the way we subtly code racial and class biases in a manner reminiscent of our treatment of vermin.

As a resident of metro Detroit, I shouldn’t be surprised to find that environmental problems are also racial problems, and vice versa.

Syria, ISIS, and Terrorism

Four of the top documentaries this year are about the civil war in Syria, including the fight against ISIS/Daesh, “City of Ghosts,” “Cries from Syria,” “Last Men in Aleppo,” and “Hell on Earth: The Fall of Syria and the Rise of ISIS,” while a fifth, “Eagles of Death Metal: Nos Amis” examines how terrorism caused by ISIS/Daesh impacted some musical Americans in Paris. Two of them, “City of Ghosts” and “The Last Men in Aleppo,” have made the Oscar shortlist. I begin by quoting the first review by The Guardian of “City of Ghosts.”

Matthew Heineman’s return to Sundance after his Oscar-nominated Cartel Land is a triumphant one. Where his previous film was a journalistic masterclass in taking access to the extreme, City of Ghosts instead turns the camera on heroic journalists themselves. In doing so, Heineman may have made the definitive contemporary documentary about the tragedy of Syria, as well as an epoch-defining piece on modern media tactics.

The film tells the story of Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently (RBSS), a group of citizen journalists who take great risks in documenting and releasing video, photo and written testimony of Islamic State atrocities in their home city. RBSS have been lauded by journalism organisations over the world, and the film opens on the bow-tied activists receiving a standing ovation in New York. However, Heineman resists romanticising RBSS – it’s clear from the first shot in the back of the head we witness, in surreptitious grainy video, that their cause is one of great personal sacrifice. While RBSS might be well known now, the impact on them as individuals isn’t. This is as much a documentary about activists struggling to hold themselves together as it is about Isis terror.

This movie is as much about press freedom as it is about civil war, which is why it may have made the cutoff for the Oscars, while “Cries for Syria” did not. Speaking of the snubbed film, The Hollywood Reporter mentions it in the same breath as both “City of Ghosts” and “The Last Men in Aleppo.”

No less than three documentaries about Syria premiered in Sundance this year. Director Matthew Heineman’s City of Ghosts looked at the citizen journalists reporting from Raqqa, the de facto capital of ISIS in Syria. Last Men in Aleppo, from Feras Fayyad, looked at the so-called White Helmets in Aleppo, a group that goes in after every air raid in the Syrian city under siege to help save victims from the rubble. Both documentaries had a rather narrow focus that allowed them to explore the human impact and dimensions of a small part of the conflict.

Evgeny Afineevsky, who directed Cries From Syria, does the opposite, packing an overview of the entire six years of the complex conflict into a film of just under two hours in an approach that’s strongly reminiscent of his Oscar- and Emmy-nominated film Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom. Essentially a primer for those who haven’t watched or read the news from a reputable source since 2011, this compact and more than occasionally gruesome item is especially strong for its first three chapters, before it tackles the Syrian refugee crisis in too superficial and sentimental a manner.

That last sentence may explain why “Cries from Syria” didn’t make the cut. Too bad, as it is almost certainly the best political documentary, if not the best documentary, period, to no longer be considered for an Oscar.

The Hollywood Reporter did a good job of introducing all three films about Syria, so I’m going to leave it to Variety to explain more about “Last Men in Aleppo.”

Unsurprisingly awarded the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, Fayyad’s film should have no trouble parlaying its Park City heat into extensive further festival play and acclaim, as well as offers from top documentary-specific distributors. Multi-platform release strategies are likely, aiming to engage audiences wary of venturing to theaters for such a heart-sinking chronicle. That said, the cinema is where “Last Men in Aleppo” firmly belongs. Together with co-director and editor Steen Johannessen, Fayyad brings a rigorous sense of craft and shock-and-awe scale to the film’s impressions of destruction, without impeding its anxious, on-the-hoof spontaneity. Any viewers coming to this after seeing “The White Helmets,” Netflix’s commendable, Oscar-nominated short on the SCD, needn’t fear seeing the same film again at greater length: This is a less cleanly packaged project, patient and nuanced in developing its individual human subjects and emotional stakes.

If anything, the Netflix film could serve as a useful primer for “Last Men in Aleppo,” which assumes a fair bit of knowledge on the audience’s part regarding who the White Helmets are and the circumstances that require them.

“Last Men in Aleppo” tied with “LA 92” for second lowest scoring film on my list to make the Oscar shortlist, but I don’t think it’s an injustice after reading the reviews of all three of the top rated movies on the Syrian Civil War, although I wish “Cries for Syria” could have made it, too.

The next two films are much more about ISIS/Daesh, which I call “The Sith Jihad.” The first is “Hell on Earth: The Fall of Syria and the Rise of ISIS” and the second is “Eagles of Death Metal: Nos Amis (Our Friends).” Variety’s review of “Hell on Earth” makes ISIS/Daesh look like Anakin Skywalker executing Order 66, making my nickname for them apt.

The radical terror army known as ISIS operates far less in the shadows than the underground rebels of Al-Qaeda. Yet for most Westerners, the image of the Islamic State remains that of an abstract and rather murky cult of hooligan warriors. “Hell on Earth: The Fall of Syria and the Rise of ISIS,” a powerful and important documentary directed by Sebastian Junger and Nick Quested, is a movie of multiple achievements, and one of them is that it lets you look right into the face of this hydra-headed paramilitary beast. We see footage of fighters from the Free Syrian Army, many of whose members were later assimilated into ISIS, entering Aleppo, a city ravaged by civil war, and they have a goon-squad fearsomeness that announces itself as beyond the law. At the risk of sounding like I’m trivializing real-world atrocity, it’s very much like that moment in “The Road Warrior” where the Lord Humungus and his brigade of biker sociopaths first roll in, the recklessness coming off them in waves.

The movie shows us disquieting footage of a public execution that culminates in a soldier bringing down his sword to slice off the head of a civilian (the film cuts away before the carnage). Later, we’re shown an image of what happens to the bodies — they are hung, upside down and headless, for three days, all to send a message to the people. The message is: This is the new law.

Eep! This is not the way I want life to imitate art.

“Eagles of Death Metal: Nos Amis (Our Friends)” is nominally a music documentary about a band and its fans who ended up being the victim’s of an ISIS attack on Paris, which I wrote about in French soccer fans sing their defiance in the face of terror. I’ll let Variety explain.

The terrorist attack that claimed 89 lives on Nov. 13, 2015 in Paris’ Bataclan theater was probably the first time most had heard of the rock act playing that night — one whose in-joke monicker was lost on a few clueless evangelicals who used the tragedy to decry the consequences of “Satan’s music.” (While their lyrics are cheerfully all for sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, their musical genre is most definitely not death metal.) Colin Hanks’ documentary “Eagles of Death Metal: Nos Amis” focuses on the titular California-based band’s principal creative relationship between co-founders Jesse Hughes and Josh Homme, the band’s connection with their French fans, and the mutual recovery that ensues after suffering the horrific trauma of terrorism.

After reading about all this death and destruction, words are failing me, so I’m moving on to a topic I like better.

Climate Change

My favorite topics for documentaries are science and the environment. Two of the top films according to my list, “Chasing Coral” and “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power,” are on that topic and made the Oscar shortlist. I have written about both films at my own blog, most recently in 2017 Environmental Media Association Awards for film and television, but also in ‘Chasing Coral’: awards and nominations and looking forward to next year’s Emmys 4 and Promoting ‘An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power’ as well as in Midweek Cafe and Lounge, Vol. 44 here at Booman Tribune, so I won’t repeat my words. I will quote what Vox wrote about “An Inconvenient Sequel,” which isn’t entirely flattering.

The word “documentary” — the “nonfiction” side of cinema — still connotes, for most people, an issue-driven, fact-based movie, one explicitly designed to convince the audience of a thesis or prompt them to take action. One of the year’s big documentaries, An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power, which served as an urgent follow-up to Al Gore’s Oscar-winning 2006 An Inconvenient Truth (and opened the Sundance Film Festival, the night before Trump’s inauguration), exemplified the genre: Its goal was to convince the audience to take climate change seriously.

But I found watching An Inconvenient Sequel incredibly strange in 2017 — especially when news surfaced that some of the story had been bent a bit in order to fit the narrative. As I wrote at the time:

Reading about a film that left me depressed about the role of facts, data, and information in our society, only to discover how it bent the truth, feels both frustrating and somehow depressingly obvious, like I should have expected it all along.

Selective editing is the documentarian’s tool, of course. But if most of the film’s hope is pinned on this example of cooperation — and yet the details I saw didn’t really line up with reality — then what are we meant to believe? Is there any chance that anyone who advocates for a cause in which they passionately believe can make headway? Or are we destined to be mired in an endless gridlock?

That really does not make me want to replace “An Inconvenient Truth” with its sequel as a film to show to my students. What about “Chasing Coral”? The Los Angeles Times reviewed the film and found it worthy.

While governments and politicians dither about global warming, the world’s undersea coral is moving toward a devastating death. If you don’t believe that, or don’t think it really matters, “Chasing Coral” presents the evidence with beauty, intelligence and a surprising amount of emotion.

One of the things that makes this such an involving documentary, the winner of Sundance’s documentary audience award, is that its cast of key characters is not the usual roundup of concerned scientists, though they are out in force.

…

Whether warning the world this way will matter, “Chasing Coral” is in no position to predict. There is some optimistic talk about “young people who can and will make a difference” and sweet shots of a determined baby turtle, but, obviously, no one knows. One thing, however, is certain. We have been warned.

I’m going to look at both films. I wouldn’t be surprised if I pick “Chasing Coral” as my next new assignment.

Libraries

Tied with “Chasing Coral” and “Cries from Syria” is “Ex Libris: New York Public Library.” With all of the war, injustice, and environmental destruction I’ve covered so far in this entry, I’m relieved to see something about government working well serving its constituents and public libraries are branches of government, whether people realize this or not.

Vox had very positive things to say about this documentary.

My pick for the year’s best documentary was Ex Libris: New York Public Library, the long-awaited magnum opus on the New York Public Library by the celebrated filmmaker Frederick Wiseman. Wiseman has been observing American institutions (like prisons, dance companies, welfare offices, and high schools) for the past half-century; for Ex Libris, he turned his camera to the New York Public Library and the many functions it fills in the city of New York.

Over a mammoth runtime — nearly three and a half hours (but I promise every moment is riveting) — we watch Wiseman construct a cogent argument for the vitality of an institution that’s constantly in danger of losing public funding. We just see what his camera captured, which in this case includes community meetings, benefit dinners, after-school programs, readings with authors and scholars (including Richard Dawkins and Ta-Nehisi Coates), and NYPL patrons going about their business in the library’s branches all over the city. The result is almost hypnotic and, perhaps surprisingly, deeply moving.

This film made the Oscar shortlist. I’m very sure this will be nominated for an Oscar and almost as sure that it will win, depending on the competition.

Sports

Like “Eagles of Death Metal: Nos Amis (Our Friends),” “Icarus” seems like an odd choice for a political film, as it’s nominally about sports. However, it ended up being about the politics of sports. The Atlantic explains how that happened.

When he set out to make Icarus, the playwright and actor Bryan Fogel had one goal: to examine how easy it is to get away with doping in professional sport. An enthusiastic amateur cyclist, he was disturbed by the fact that someone like Lance Armstrong could cheat for so many years and never fail a single drug test. “Originally,” he explains in the film, “the idea I had was to prove the system in place to test athletes was bullshit.”

What actually happened was a bit like tugging on an errant thread and having the entire clothing industry unravel right on top of you. Fogel, while conducting a human guinea-pig experiment in which he took performance-enhancing drugs to prepare for a race, was connected with a Russian doctor who ended up blowing the whistle on a state-sponsored doping scheme that had been ongoing in Russia for decades. Icarus, initially intended as a Super Size Me-style effort to poke holes in the anti-doping system, ended up capturing the maelstrom of one of the biggest scandals in sporting history, while former anti-doping officials were dying under mysterious circumstances and the IOC was pondering whether Russia should be banned outright from the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Russia may not have been banned from last year’s Summer Olympics, but, as CNN reported, Russia banned from Winter Olympics but ‘clean’ athletes can compete. That news makes this film extremely timely.

Refugees

The lowest ranking film on my list to make the Oscar shortlist is “Human Flow.” As I have been at this post for several hours and it’s the last film, I’ll let Variety do my work for me.

Some time ago, Ai Weiwei’s fame eclipsed his art, so what he does with that fame really does matter. In his first feature-length documentary (he’s made video installations in the past), the Chinese dissident stamps the international refugee crisis with his imprimatur, lending his name to the cause in the hope of raising awareness of just how serious the calamity has become. This leads to several problems, not least of which is that if you need a celebrity to tell you there’s a crisis, you really haven’t been paying attention. Perhaps Ai knew that, because “Human Flow” is basically Refugees for Dummies, a primer on global displacement with theatrical releases all lined up and an Amazon deal that’s bound to see significantly more traffic than box office cash registers or, crucially, refugee NGOs.

This movie serves as a good example of “everything is connected to everything else” as it connects to both the Syrian refugee crisis featured in “Cries from Syria” and the environmental degradation mentioned in “An Inconvenient Sequel.” That alone makes it worthy of inclusion and consideration by the Motion Picture Academy.

Modified from the original at Crazy Eddie’s Motie News.