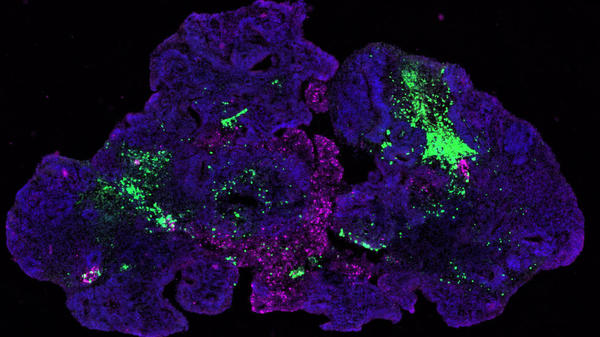

Image Credits: Image courtesy of the Arlotta laboratory..

I’m not in the least surprised that if you grow human brain cells in a Petri dish, eventually they will create neurons that fire in synchrony and emit brain waves. Scientists are growing these things and calling them “organoids,” and they are already trying to use them to steer a robot. They can introduce retinal cells that make these things sensitive to light, and I won’t be surprised if they begin to “learn” as a result. Nerve cells could introduce sensation and pain, along with all the learning that goes with that. So, now that they’re pretty far along in the process, they’re finally beginning to have a couple of ethical concerns and philosophical debates about what, in fact, an organoid actually is. The researchers may be a little biased but they say that they’re not creating sentient life.

As the organoids mature, the researchers also found, the waves change in ways that resemble the changes in the developing brains of premature babies.

“It’s pretty amazing,” said Giorgia Quadrato, a neurobiologist at the University of Southern California who was not involved in the new study. “No one really knew if that was possible.”

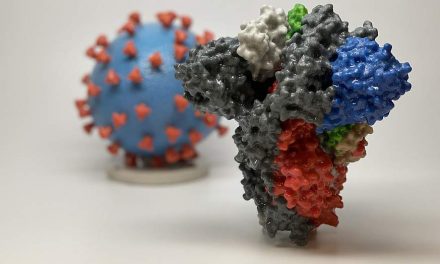

But Dr. Quadrato stressed it was important not to read too much into the parallels. What she, Dr. Muotri and other brain organoid experts build are clusters of replicating brain cells, not actual brains.

To me, this is the flip side of medieval-level thinking about a divine spark or immaterial soul being a necessary component of human consciousness. The scientists err in thinking that human brain cells need an actual person or body to achieve consciousness. But that’s unlikely. A cluster of cells is a body. As some point, a complex enough system of human brain cells will go through a transition and create the soul-like conditions we associate with consciousness. The things that might prevent this, like the ability to sense the outside world, can be overcome by giving the brain cells the kinds of sensory cells we use to interact with the physical world.

So, if you start growing a human brain and give it the ability to sense light and sound and temperature, you should expect it begin to responding like a human brain in a human body. I’d still expect this thing to be less than a fully conscious entity, but only because you need to be fully human in order to act fully human. You need hunger and sexual drives, for example, and interpersonal relationships. But just because you aren’t creating fully human self-aware consciousness doesn’t mean that you aren’t creating some kind of consciousness.

None of this should be as controversial as it seems to be in the research community. If consciousness is explained by the action of brain cells, then growing brain cells should achieve consciousness. If, as we know, the brain cells are insufficient for this by themselves, then introducing additional cells that help the “brain” interact with the physical world and begin to learn from it, will probably get you there. If you want the thing to avoid extremes of temperature, give it enough cells to make it ambulatory, and it will probably learn to move away from heat and cold.

The only limitation is on how much a human body you give the thing. Eventually it will have a stomach and gonads or ovaries. I don’t know how far you can go before you have to concede that you’ve grown a person in a Petri dish, but there’s obviously some threshold beyond which you can’t go.

But they aren’t overly concerned about thresholds. The promise of medical breakthroughs is leading them in another direction, and they’ve now sent some organoids into space to see how they develop in zero-gravity environments.

For now, these debates matter to a few scientists: the master chefs who can reliably make enough brain organoids to run experiments. But Dr. Muotri and Dr. Trujillo hope to automate the process, so that other scientists can make lots of cheap, high-quality brain organoids.

“That’s our concept — plug and play,” said Dr. Muotri. “We want to make farms of these organoids.”

The organoids sent to space may help make that concept a reality. The box in which they were housed is a rough prototype of a device that someday might produce organoids without human intervention.

The astronauts aboard the space station simply installed the box, turned on the power, and let it run on its own.

On a recent morning, Dr. Muotri wanted to check on his space organoids. Cameras inside the box snap pictures every half-hour, but all the pictures Dr. Muotri had seen were obscured by unexpected air bubbles.

Now, to his delight, the bubbles were gone from the latest image. On his computer monitor, he saw a half-dozen gray spheres floating on a beige background.

“They’re rounded, and they more or less have the same size,” he said. “You don’t see them fusing or clustering together. So this is all good news.”

If all this work does eventually lead to mass-produced brain organoids, Dr. Muotri won’t mind if his artisanal organoid-growing skills become obsolete.

This is all a great scientific achievement, but they’re beginning something that will create a major ethical problem. If we harness human brain cells to serve as operating systems for robots, we will find out that human brain cells don’t need human bodies to act human. Human consciousness emerges out of a complex physical network. You can plug and play with it, but we’re not computer software and we can’t be programmed to reliably follow instructions.It would not be ethical to take that kind of free will away from us and it wouldn’t be smart to rely on computers that have free will.

This also reflects a kind of persistent human conceit about consciousness, where we are willing to assign it to our own species but are very reluctant to acknowledge consciousness in other animals or lifeforms. We do this, I believe, not only for anachronistic religious reasons but because we must consume other life forms in order to survive. If we consider the destruction of consciousness a great crime, then we can’t grant it to the things we eat. It would be better to admit that we favor our own kind, not arbitrarily but because we want to live a civilized life.

But here we are talking about giving consciousness to non-lifeforms. Or, perhaps more accurately, we’re talking about turning robots into lifeforms and then pretending that we haven’t done this for completely arbitrary reasons.

Simply put, if you grow a brain and attach it to the physical world, you’ve created a new lifeform, and whether this thing has consciousness will depend mainly on how many tools you give it to work with. It will have all the potential of any other human brain.

So, we should be wary of an effort to mass produce or “farm” organoids. It will be very easy to lose control of a process like that, and we should put a halt to this until some of the ethical questions are resolved and the full risks are examined.