Image Credits: WikiCommons.

Robert Draper of the New York Times recounts part of an interview he conducted recently with Fiona Hill, a Russia expert who served in the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations. The following section pertains to briefing a Hill provided to George W. Bush and Dick Cheney before the NATO summit in Bucharest, Romania in February 2008. It’s of historical interest because the subject was the advisability of offering NATO membership to former Soviet Socialist Republicans Georgia and Ukraine. Hill thought it was far from a good idea. Bush and Cheney did not heed her advice, although sensible European resistance to the idea forced an unfortunate compromise that the world is still paying for.

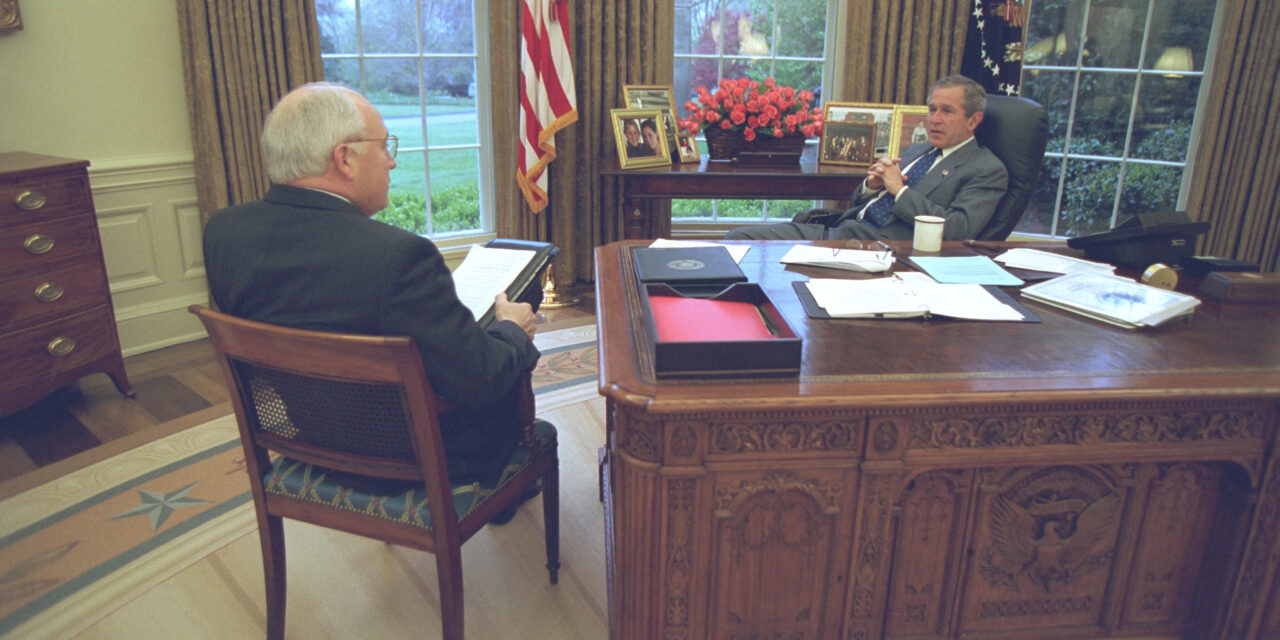

In the Oval Office, [Fiona] Hill recalls, describing a scene that has not been previously reported, she told Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney that offering a membership path to Ukraine and Georgia could be problematic. While Bush’s appetite for promoting the spread of democracy had not been dampened by the Iraq war, President Vladimir Putin of Russia viewed NATO with suspicion and was vehemently opposed to neighboring countries joining its ranks. He would regard it as a provocation, which was one reason the United States’ key NATO allies opposed the idea. Cheney took umbrage at Hill’s assessment. “So, you’re telling me you’re opposed to freedom and democracy,” she says he snapped. According to Hill, he abruptly gathered his materials and walked out of the Oval Office.

“He’s just yanking your chain,” she remembers Bush telling her. “Go on with what you were saying.” But the president seemed confident that he could win over the other NATO leaders, saying, “I like it when diplomacy is tough.” Ignoring the advice of Hill and the U.S. intelligence community, Bush announced in Bucharest that “NATO should welcome Georgia and Ukraine into the Membership Action Plan.” Hill’s prediction came true: Several other leaders at the summit objected to Bush’s recommendation. NATO ultimately issued a compromise declaration that would prove unsatisfying to nearly everyone, stating that the two countries “will become members” without specifying how and when they would do so — and still in defiance of Putin’s wishes. (They still have not become members.)

“It was the worst of all possible worlds,” Hill said to me in her austere English accent as she recalled the episode over lunch this March.

The reason the compromise was the worst of all possible worlds is because it wound up offering Georgia and Ukraine no protection while spurring Putin into defensive action. It also gave Georgia and Ukraine an unrealistic optimism that the promise of actual membership might one day be fulfilled.

This is not to argue that the best solution would have been to foreswear NATO membership altogether in perpetuity, but the question should have been artfully put off to another year and another summit. It was foreseeable that Europe would not risk nuclear war to defend Ukraine’s territorial integrity. As things stand today, it’s surprising that NATO is taking as many risks in this regard as they are by supplying all manner of assistance to Ukraine as it tries to fend off Putin’s invasion. But an innovation of Article 5, which would put all of NATO at war with Russia is still almost unthinkable in a nuclear world, and it was unthinkable in 2008, t00. That’s why NATO membership should not have been dangled.

Far better was gradual economic and cultural inclusion of Ukraine and Georgia. A good example of this was the decision to have Poland and Ukraine jointly host the Euro 2012 soccer championship. That’s the kind of passive aggressive move toward integrating Ukraine with the West that might have worked if not for the 2008 promise of NATO membership.

I won’t engage much with arguments that rely on Putin being less of a sociopath if only Western leaders had made different decisions. In fact, Putin should have been assessed as a dangerous maniac based on how he treated Chechnya prior to even becoming the leader of Russia. Efforts to integrate Russia with the West were well-meaning and a good idea for the same reasons it made sense to follow that path with Ukraine and Georgia, but they had to contend with the stubborn fact that Putin had no interest in being one among equals.

This mainly is water under the bridge at this point, but it shows how one lazy decision made against the advice of an in-house expert can reverberate for decades and cost countless lives.