Image Credits: Photo: Getty Images.

Keith Spencer of Salon tells us that picking a centrist candidate for president is a mistake.

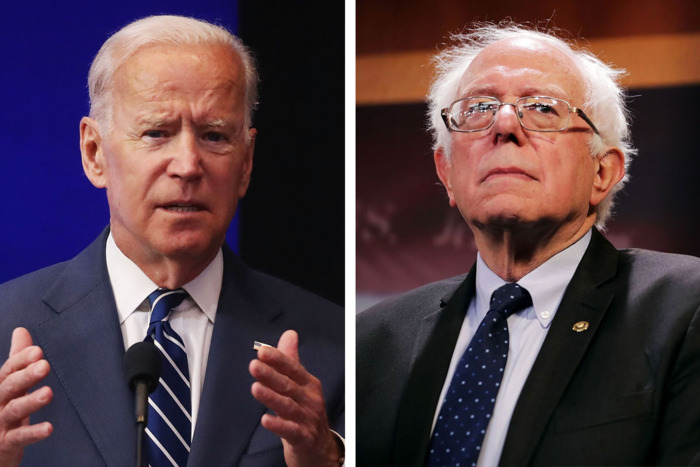

As the Democratic establishment and its pundit class starts to line up behind the centrist nominees for president — mainly, Joe Biden, Cory Booker and Kamala Harris — the party’s head-in-the-sand attitude is especially troubling.

To marshal his argument, Spence utilizes French political economist Thomas Piketty’s 2013 book, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century.” The basic insight isn’t novel. It’s a straightforward socialist interpretation of how and why people vote they way they do, with an exhortation that all the lower classes of the world unite in a transnational color-blind coalition against their wealthy oppressors.

For example, the people of states like Oklahoma used to vote for left-wing populists and now they vote for right-wing conservatives. For Spencer, “these rural whites saw their struggles and their oppressors reflected back in the rhetoric of the socialist candidates and thinkers that spoke to them, the “egalitarian internationalists” to use Piketty’s language.” But now the only place they see their struggles reflected is on their television screens when they’re watching “Fox News and their ilk.”

The reason they abandoned the left for the right is because the Democratic Party embraced neoliberalism and thereby created a vacuum that the right gladly filled:

The [Democratic] party’s leaders see themselves as the left wing of capital — supporting social policies that liberal rich people can get behind, never daring to enact economic reforms that might step on rich donors’ toes. Hence, the establishment seems intent on anointing the centrist Democrats of capital, who push liberal social policies and neoliberal economic policies.

One complication with this theory is that a very large percentage of the rural whites who abandoned the New Deal coalition did so for reasons of race and religion that were only tangentially related to economic policies, if at all. In the post-Trump era, one challenge in convincing the Democrats to consider these people’s needs is that they’re widely considered to be too “deplorable” to court. They now exist, in a sense, on the other side of a cultural divide. The socialists always lament this and say it is unnecessary, but they often come off as belittling the concerns of the people on the left side of this battle. This is largely why Bernie Sanders struggled to win the support of black voters in 2016. Black folks are too intimately familiar with the reasons that rural whites aren’t on their side to believe they can just join up with them in an international class struggle.

There are some additional historical challenges to the socialist critique. For example, the last Democrat to do well with rural whites was Bill Clinton, who also happens to be the Democrat most associated with moving the party away from the New Deal politics of the past into a newer era of neoliberal policies. He won enough votes in the middle to reverse the pattern that had developed in the 1972-1988 period where the Democrats were more likely to lose 49 states than to win the presidency. There are ways to explain away Clinton’s performance, but we should be clear that it at least needs to be examined.

To begin with, he actually won twice so we cannot flatly declare that the model has no potential. Perhaps it was an anomaly that cannot be easily replicated. Or, maybe there was a delayed reaction to Clintonism that had the effect over time that Piketty describes in his analysis. These are real possibilities that should be given serious consideration, but we have to at least look at them before we can begin to make conclusions about what kind of candidate can win in 2020.

There are many ways to approach the upcoming election, and the socialist critique is not the most compelling. An extremely simple model says that if one party lurches ideologically out of the mainstream, the other party can win simply by occupying the vacated territory in the middle. However, if both parties vacate the middle, then it’s far harder to predict which side will win.

This is what is worrying people like Steve Rattner who wrote recently in the New York Times about the modeling of the 2020 election that is strongly predicting that Trump will be reelected. That is the conclusion of Yale Professor Ray Fair, Moody’s Analytics economist Mark Zandi, and Donald Luskin of Trend Macrolytics, who have all come to the conclusion that Trump should be favored independently of each other. It’s true that Trump is unpopular and divisive, but he’s the incumbent in a fairly strong economy with low unemployment. Historically, presidents in Trump’s position have won reelection with ease.

It seems that Democratic voters sense this, which is why the primary is shaping up to be a battle between Joe Biden and everyone else. It’s why Biden is the overwhelming first choice of black voters- a key progressive bloc of the party that seems indifferent to the promise of a color-blind international socialist revolution.

Of course, not everyone on the left agrees that the foremost goal should be winning the 2020 election. If you’d rather lose than win with the wrong kind of candidate, then that’s a different kind of discussion. What Spencer is saying, however, is that picking a centrist candidate like Biden, Booker or Harris will cause the Democrats to lose. It’s a little unclear why he included Harris in this troika of would-be failures, but this doesn’t really affect the merits of his analysis. The idea is that the Democrats are losing because they’re failing to unite the underclasses under one banner, and that’s a problem that developed over a half a century rather than something that will be reversed because the Democrats pick Sanders or Warren or Mike Gravel as their nominee.

More to the point, any strategy that presumes that America as a whole or the Democratic Party in particular can wave away the influence of race in the 2020 election seems to be oblivious to the greater trends in international politics that are unfolding over immigration, national sovereignty, and cultural pluralism. A Democratic nominee should certainly try to appeal to anyone who stands to benefit from greater investment in schools, infrastructure, health care, worker’s rights, and retirement security. That doesn’t mean they’ll be successful in bringing a bunch of Fox News-watching religious conservatives over to the proletarian cause.

It looks like 2020 is shaping up to be a very high turnout election, which means that partisans on both sides will be getting themselves to the polls. More than in most recent elections, this makes the real battle a battle for the middle. The Republicans have abandoned the middle and are pursuing a base mobilization strategy that alienates more than half of the voters. It seems like the Democrats should be positioned to win simply by playing it safe, but if they decide to take big risks in search of big rewards, they could blow their advantage.

There are solid reasons to conclude that given challenges like Climate Change, we don’t have the luxury of playing it safe. I think that is probably true, so my analysis of how to win isn’t my only consideration. I just don’t like being told that the playing to the middle is the surest way to lose. It’s not.