Image Credits: Photo: Getty Images.

It’s easy to get whiplash these days, especially if you believe in data. This morning, you can learn from Gallup that the country remains ideologically slanted to the right:

“As Americans continued to lean more Democratic than Republican in their party preferences in 2019, the ideological balance of the country remained center-right, with 37% of Americans, on average, identifying as conservative during the year, 35% as moderate and 24% as liberal.”

You can also learn from Daily Kos Elections that Donald Trump’s reelection prospects have never looked worse:

We've swapped in some new @Civiqs polls on the @DKElections home page. One is Trump's re-elect vs. a generic Dem, which just ticked up to its widest spread ever, 49 D, 43 Trump. The trend overall has not been good for Trump https://t.co/pTyjiBqJ9S pic.twitter.com/HKSPR2945o

— Daily Kos Elections (@DKElections) February 18, 2020

You can read Eric Levitz’s big piece in New York magazine that explores the hard-left leanings of Millennials and Generation Z.

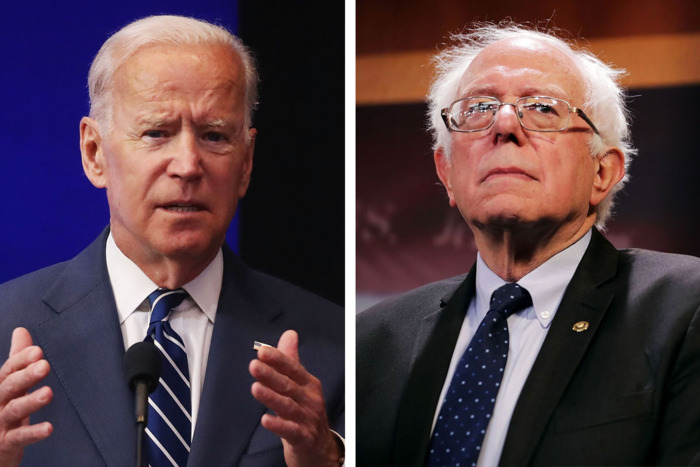

Blue America’s gaping chasm of a generation gap has been a — if not the — defining feature of the Democratic primary race thus far. An Economist/YouGov poll released this week found that 60 percent of Democrats younger than 30 support either Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren; among those 65 and older, the progressive candidates’ combined total was 27 percent. Before the Vermont senator’s strong showings in Iowa and New Hampshire, surveys showed an even wider age divide: In late January, Quinnipiac had Joe Biden leading the field nationally — even as he trailed Bernie Sanders among voters 35 and younger by a margin of 53 to 3 percent. Exit polls from New Hampshire affirmed this generational split, with Sanders winning 47 percent of voters 18 to 29, but just 15 percent of those over 65.

Technically, it’s possible for all of these things to be true at the same time despite the fact that they seem to tell contradictory stories. If you’re trying to put together this puzzle to see what it portends for the upcoming election, it seems like a very daunting task. We’re accustomed to seeing a gender gap and voter preferences starkly divided by region and race, and we know that the Electoral College is very capable of rendering a different verdict from the popular vote. We’ve never seen generational splits like this, however, and pollsters aren’t giving us the information in a way that really allows us to understand how it might shape the outcome in November.

For example, we don’t know if the youth vote is as divided by region as the rest of the electorate. Are the kids in Oklahoma as socialist friendly as the left-leaning kids in Oregon? How about in the rural areas of the Rust Belt? Can Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren hope to outperform Hillary Clinton in small town Pennsylvania because folks under thirty there will vote differently from their MAGA hat-wearing parents? How would these same kids feel about Joe Biden or Michael Bloomberg? What would this age difference look like with Pete Buttigieg on the ballot? Finally, how much youth turnout would be necessary to overcome the natural tendency of older votes to hit above their weight in the voting booth?

We can ask similar questions about the folks over sixty-five. The data suggest that they’d be far more likely to back a candidate perceived as moderate than a strong progressive. To what degree is this true, and at what point would it overwhelm any surge in voter participation from younger voters? We might only need the answer to this question in a small handful of swing states.

I tend to focus more on the urban/suburban vs. rural/small town split, as it helps me model what it will take to win in the traditionally blue states that Trump carried in 2016. Sanders-style Democratic socialism doesn’t play well in the affluent suburbs outside Philadelphia where I live. My county voted for George W. Bush twice before splitting between Obama, Romney, and Clinton. Clinton actually did the best of the bunch, but there’s a lot of potential swing depending on the candidates on offer.

And there’s some reason to believe the youth vote here will act differently from the youth vote in less wealthy areas. Eric Levitz looks at the recent results out of New Hampshire in the context of data showing that real median income for college grads looks much different for kids that attend elite vs. ordinary colleges.

A vulgar Marxist looking at Bloomberg’s chart might predict that the college students and graduates of less prestigious, public universities — who have been most disserved by the “knowledge economy” myth — would be even more inclined toward left-wing politics than their Ivy League peers. And the results of the New Hampshire primary lend credence to that view: While Pete Buttigieg held his own in the town of Hanover, home to Dartmouth, Sanders cleaned his clock in the precincts surrounding the University of New Hampshire.

Since the popular vote doesn’t determine the winner of the presidential election, it matters a lot how sentiments in the youth vote differ by state, and also how turnout might differ by region. It’s quite possible that one Democrat could create a successful distribution of votes while another would not, despite them both getting about the same number of total votes across the entirety of the country.

Yet, regional and urban/suburban vs. rural/small town polarization seems to be the most immutable and growing phenomenon of the Trump Era. It’s hard to bet on any Democrat being able to stem or especially reverse this trend. A candidate who we can expect to underperform Clinton among the over-30 crowd in the suburbs and among voters over 65 would need to make up for it by over-performing by a bigger amount with the under-30 crowd and in Trump’s rural areas of strength. And they’d have to do this in clearly defined states like Michigan and Pennsylvania.

It’s hard to gamble on this happening when the more natural and obvious road to victory is to roll up bigger margins in the suburbs than Clinton did, which seems to be the trajectory we’re on, while hoping that any Democrat will do better than Clinton with the youth vote in rural areas.

The surest road to defeat seems to be entering the contest with a badly divided Democratic Party where there are folks who actually prefer Trump to their own party’s candidate, and also a large contingent of people who will sit it out because they’re angry at how their preferred candidate was treated during the primaries.

It seems obvious that a more progressive kind of politics is on the horizon, but I don’t know if we’ll be there yet in 2020.