Image Credits: Nati Harnik/Associated Press.

As I sit here with my power newly restored more than forty-eight hours after a wind storm, and still without internet except through my iPhone’s hotspot (which, I am notified, will soon be throttled for overuse), I can understand why so many Americans feel like the country is broken. It’s a theme today at the New York Times where columnists Bret Stephens and Thomas Edsall spell it out for us.

Stephens is being widely mocked for penning a column entitled The Case for Donald Trump…By Someone Who Wants Him to Lose, and I can understand why progressives are losing their patience with this kind of production from The Gray Lady. But the column is really a plea for opponents of Trump to “take our heads out of the sand.” If nothing else, it does a decent job of explaining that the Establishment is failing because it has a shitty record.

Edsall’s piece, A ‘National and Global Maelstrom’ Is Pulling Us Under, is much better and far more terrifying.

The coming election will be held at a time of insoluble cultural and racial conflict; a two-tier economy, one growing, the other stagnant; a time of inequality and economic immobility; a divided electorate based on educational attainment — taken together, a toxic combination pushing the country into two belligerent camps.

I wrote to a range of scholars, asking whether the nation has reached a point of no return.

The responses varied widely, but the level of shared pessimism was striking.

If I could sum up the common theme Edsall received in response to his inquiries, it’s a struck-dumb realization by our educated elites that at least half the electorate is beyond reason and prepared to deliberately destroy this country for spite. It’s a crisis of faith in the people, which hasn’t yet curdled into a loss of faith in the virtues of our democratic system. It’s not the virtues that are openly doubted at this point, but rather the prospects for survival.

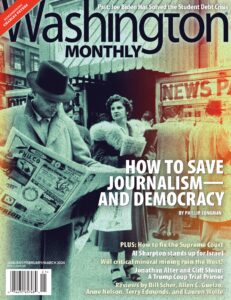

It’s a theme my brother tackles in the cover story for the Jan/Feb/Mar 2024 issue of the Washington Monthly. I just checked and that story has not gone live, although subscribers have already received their copy in the mail.

Phil explains how the monopolization of media has contributed to the brokenness we’re all experiencing, including the broken moral and mental capabilities of the American electorate.

Instead, it is a direct result of specific, boneheaded policy choices that politicians in both parties made over the past 40 years. By repealing or failing to enforce basic market rules that had long contained concentrated corporate power, policy makers enabled the emergence of a new kind of monopoly that engages in a broad range of deeply anticompetitive business practices. These include, most significantly, the cornering of advertising markets, which historically provided the primary means of financing journalism. This is the colossal policy failure that has effectively destroyed the economic foundations of a free press.

Since he came armed with solutions, I welcomed my brother’s piece as an antidote for my own deep and growing sense of helplessness. Because, to be honest with you, I generally am more in the Richard Haass camp. Haass told Edsall, “I am no longer confident there is the necessary desire and ability to make this country succeed. As a result, I cannot rule out continued paralysis and dysfunction at best and widespread political violence or even dissolution at worst.”

And if not Haass, then Jack Goldstone, a professor of public policy at George Mason University, who told Edsall, “if the G.O.P. wins in 2024 or even wins enough to paralyze government and sow further doubts about the legitimacy of our government and institutions, then we drift steadily toward Argentina-style populism, and neither American democracy nor American prosperity will ever be the same again.”

I most definitely identify with this:

Isabel Sawhill, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote in an email that pessimism has become endemic in some quarters: “I find that many of my friends, relatives and colleagues are equally concerned about the future of the country. The worst part of this is that we feel quite helpless — unable to find ways to improve matters.”

The helplessness really draws from the inability of anyone with expertise and influence to convince the public about the true nature of Donald Trump’s character and motivations. And maybe Stephens is onto something when he writes, “My pet theory is that, if Republican voters think the central problem in America today is obnoxious progressives, then how better to spite them than by shoving Trump down their throats for another four years?”

But, truthfully, Stephens is probably more on point here:

As writers like Tablet’s Alana Newhouse have noted, brokenness has become the defining feature of much of American life: broken families, broken public schools, broken small towns and inner cities, broken universities, broken health care, broken media, broken churches, broken borders, broken government. At best, they have become shells of their former selves. And there’s a palpable sense that the autopilot that America’s institutions and their leaders are on — brain-dead and smug — can’t continue.

Which is really what my brother Phil is arguing, too. With respect to the crisis in journalism, he writes, “Simply put, it requires returning to the same basic anti-monopoly principles that Americans used during previous revolutions in communications technology to preserve our First Amendment rights.” As he’s been arguing for years now, anti-competitive practices are at the root of problems not just in media and journalism but in health care and in the regional inequality that is driving rural and small-town America into the hands of the fascist right.

In a piece just published in Politico Magazine on Nikki Haley’s campaign, Jonathan Martin makes an interesting observation about two recent events in Iowa:

The most memorable feature of Haley’s otherwise forgettable gathering was not what she said but the nature of her audience — and how it explains why Trump is poised to win overwhelmingly in Iowa on Monday but will face the same general election challenges in 2024 he did in 2020.

I struggled to find a single attendee in the suburban strip mall tavern who was not a college graduate. Similarly, the day before, I couldn’t find a Haley admirer who showed up to see her in Sioux City who was not also a college graduate.

Trump’s base of support is increasingly made up of non-college graduates, and this is transforming the Republican Party into a right-wing populist movement. There is nothing more dangerous to a representative form of government, and it’s proceeding this way in part because the Democratic Party has not fought strongly enough against monopolies.

My pessimism is really drawn from my suspicion that it’s too late. The Biden administration understands the problem and has the best antitrust policies we’ve seen in decades, but with Congress deadlocked, they simply lack the power to do more than tinker around the edges.

I am not a fan of Bret Stephens, but he’s doing a service in trying to explain Trump’s appeal to Democrats who can’t get beyond his personal failings. I am just hoping it’s not too late.