Image Credits: Mike Coppola/WireImage for NARAS.

Writing for Lawfare, Susan Hennessey and Quinta Jurecic find themselves coming to the same conclusion I reached after reading the Mueller Report. The Office of Special Counsel reached two conclusions that, when combined, lead inexorably to the conclusion that the House of Representatives has a constitutional duty to hold an impeachment inquiry.

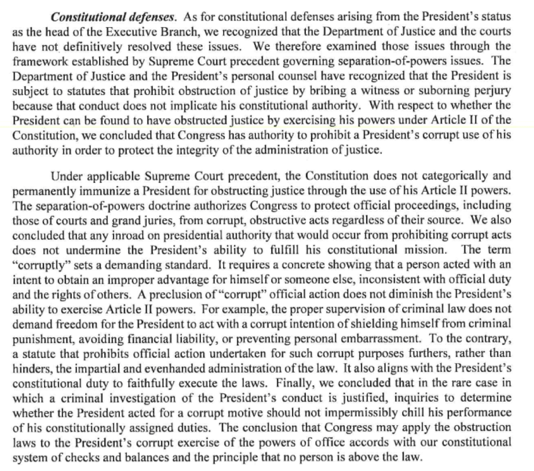

The first conclusion is that the president has committed obstructive acts for which there are no valid or compelling legal or constitutional defenses. The second conclusion is that the president cannot be formally accused of this unless he is afforded some forum in which he can mount a defense. The only forum available, since Department of Justice policy precludes indicting a sitting president, is a House impeachment inquiry followed, if necessary, by a Senate impeachment trial.

“The Mueller Report describes, in excruciating detail and with relatively few redactions, a candidate and a campaign aware of the existence of a plot by a hostile foreign government to criminally interfere in the U.S. election for the purpose of supporting that candidate’s side. It describes a candidate and a campaign who welcomed the efforts and delighted in the assistance. It describes a candidate and a campaign who brazenly and serially lied to the American people about the existence of the foreign conspiracy and their contacts with it. And yet, it does not find evidence to support a charge of criminal conspiracy, which requires not just a shared purpose but a meeting of the minds.”

“Here is the other bottom line: The Mueller Report describes a president who, on numerous occasions, engaged in conduct calculated to hinder a federal investigation. It finds ample evidence that at least a portion of that conduct met all of the statutory elements of criminal obstruction of justice. In some of the instances in which all of the statutory elements of obstruction are met, the report finds no persuasive constitutional or factual defenses. And yet, it declines to render a judgment on whether the president has committed a crime.”

“Now, the House must decide what to do with these facts.”

The House leadership appears reluctant to accept their fate. They’re clearly concerned that an impeachment inquiry will be a self-injurious exercise that leads in the end to an acquittal of clearly criminal behavior by a Republican-majority Senate. They feel that they are currently on track with a solid plan to retain their House majority and set the field up nicely for the eventual Democratic Party presidential nominee. They’re even hopeful that they colleagues in the Senate might be able to retake majority status after the 2020 elections. They could win the trifecta and have total control in Washington DC beginning in January 2021. Why put all of that at risk for something that will not succeed in removing the president from power or adequately hold him accountable?

These are very valid concerns. Good politicians have to think in political terms. But the problem is that they cannot avoid a decision. They “must decide what to do with these facts.” There’s even a sense in which the president deserves to have the benefit of impeachment. To see what I mean, consider the following comments from Rudy Giuliani:

Trump attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani said that since obstruction-of-justice charges were not brought against Trump, Mueller should not have so thoroughly detailed the acts that were under examination, such as the president’s attempts to remove the special counsel and curtail the probe.

“The narrative is written as if it’s all true and somebody proved it. Nobody proved it,” Giuliani said in an interview Friday. “I’m frustrated by the report because in some ways I’d love to have a trial and prove that it’s not true.”

The Office of Special Counsel almost agrees with Giuliani. They refuse to say that Trump is guilty of obstruction of justice because, in the absence of formal charges, he is not able to respond in a judicial proceeding. What they do instead, is provide Congress with the evidence and ask them to provide that forum. Giuliani says that “in some ways” he wants a forum to defend the president, and that is clearly what Mueller believes he should have.

While the Report discusses the unfairness of leveling DOJ accusations against a president who can not hope to clear his name until he is out of office, it also says that Congress can and should exercise its “authority to prohibit a President’s corrupt use of his authority in order to protect the integrity of the administration of justice.” They write that Congress “may apply the obstruction laws to the President’s corrupt exercise of the powers of the office,” and that doing so would “accord with our constitutional system of checks and balances and the principle that no person is above the law.” In other words, since the DOJ (by the terms of its own policies) cannot serve as the check on this behavior, the constitutional responsibility for doing so must lie with Congress.

The House leadership cannot escape that responsibility, but it’s also unfair to the president to have the Office of Special Counsel’s accusations hanging over his head without the ability to defend himself, which is why Giuliani is “frustrated.” If the House were to deny Trump the opportunity to defend himself they would in a real sense be denying him his rights.

You might think I am being too cute by half with this argument, but it’s actually a logical result of how our system is designed and how it has been interpreted by the Department of Justice and the Office of Special Counsel.

If the president cannot be accused of a crime without providing him a forum to defend himself, then a forum must be provided when he has been accused of a crime. Otherwise, he simply cannot be accused of crimes, which would place him above the law.

Another logical conclusion we can derive from this is that the decision on whether or not to initiate an impeachment hearing is not a matter of political calculation. Without the inquiry, the whole system of checks and balances breaks. It would almost be equivalent to Congress refusing to appropriate money for the judicial branch of government. No one could be convicted of a crime because there would be no money to pay for their trials.

We should remember, too, that an impeachment inquiry is not the same thing as a decision to impeach the president and take the case to the Senate for trial. It’s just an inquiry, not an indictment. The House has an obligation to take up the obstruction charges, at a minimum, and give the president the opportunity to clear his name. They also have an obligation to, as Muller says, “protect the integrity of the administration of justice” by using their authority to apply “the obstruction laws to the President’s corrupt exercise of the powers of the office.”

On both counts, an impeachment inquiry is logically and constitutionally inescapable in this instance. A failure to meet this challenge might be a safer choice in an electoral sense, but it would leave our system in tatters.